Evolution

Evolution

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Life Sciences

Life Sciences

Something’s Fishy With BioLogos’s Description of Fish Fossil Record

In a prior post, I discussed how BioLogos’s website has a page titled “What does the fossil record show?” which is conspicuously missing any mention of the Cambrian explosion, or any other explosions in the history of life. The page also has other errors and omissions.

In a section titled “Evidence of Gradual Change,” it states: “At 500 million years ago, ancient fish without jawbones surface.” Actually, the first known fossils of fish are from the lower Cambrian, meaning that their date is probably closer to 530 m.y.a., near the beginning of the Cambrian period. A Nature paper reporting this find was titled “Lower Cambrian vertebrates from south China.” It noted: “These finds imply that the first agnathans may have evolved in the earliest Cambrian.” So animals as complex as vertebrate fish appear at the beginning of the Cambrian explosion without any clear evolutionary precursors. BioLogos doesn’t mention this abrupt appearance, and places them much later.

Chronological and Digital Errors

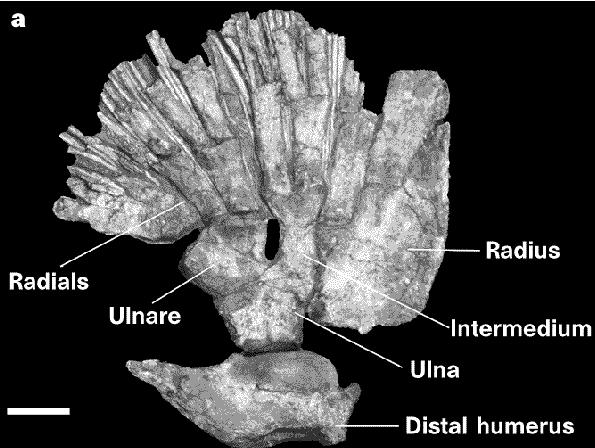

But this is just the beginning of fish-related problems on the page. Later, in a section titled “The Transition to Land: Sea Creatures to Land Animals,” the BioLogos fossil record page states, “Fossils of land animals, or tetrapods, first appear in rocks that are about 370 million years old.” It then argues: “But in 1998, scientists found a fossilized fin of just the right age — 370 million years old — with eight digits similar to the five fingers humans have on their hands and distinct humerus, radius and ulna like an early tetrapod, as shown in Figure 1.”

“Just the right age”? Well, that statement is no longer correct, since in early 2010 tetrapod tracks “showing individual digits” (Nature news) were discovered from 397 million years ago. It seems that the page needs updating to recognize the fact that if you want to find ancestors to tetrapods, you must now look before 397 m.y.a. Fossils from 370 million years ago are not “of just the right age.” By 370 m.y.a., tetrapods had apparently been around for tens of millions of years.

But there’s something else fishy here. The quote above claims that the fin has “digits” and refers to Figure 1, which is a redraw of a figure from the original Nature paper, seen below:

Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Edward B. Daeschler and Neil Shubin, “Fish with fingers?,” Nature, Vol. 391(6663):133 (1998).

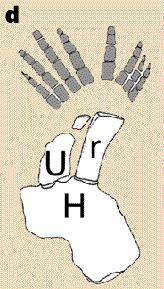

BioLogos claims this fin had “digits.” But if you’ll notice, the diagram from the original paper doesn’t corroborate that. Rather the Nature paper’s diagram, as seen above, quite conspicuously labels the bones as radials, a common bone in fish fins. There’s a good reason for this, because digits in tetrapod limbs are significantly different from radial bones in fish fins. Compare the messy jumble of radials in the diagram above with the nice, neatly organized digits of a true tetrapod, Acanthostega, seen below:

Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Edward B. Daeschler and Neil Shubin, “Fish with fingers?,” Nature, Vol. 391(6663):133 (1998).

There’s marked and significant difference between the nicely lined up phalanges in the digits of Acanthostega and the radially arrayed radial bones — which are not lined up in any digit-type formation — in the fish fin. Unlike phalanx bones in digits, the radials in the fish fin can articulate multiple other radial bones. Some don’t articulate anything at all. This is easily seen in the diagram from the Nature paper above. There are also significant differences in size and shape. Call them what you like, but this fish fin doesn’t have anything like the digits in a true tetrapod limb.

What is more, the “radius” and “ulna” of the fin have a significantly different shape and orientation from a true radius and ulna in tetrapods. In tetrapods these bones articulate metacarpals, which are not existent in the fin. For details, see: An “Ulnare” and an “Intermedium” a Wrist Do Not Make: A Response to Carl Zimmer.

Calling this a fish with “digits” seems a little fishy to me.

More Incorrect Tiktaalik Arguments

A final problem with the page comes when it cites Tiktaalik‘s stratigraphic placement as evidence for Darwinian evolution: “Tiktaalik was found in a rock formation that was approximately 375 million years old, in line with same narrow time period mentioned above.” Of course, as we’ve recently seen, this argument is no longer valid since tetrapod tracks are now known from 397 m.y.a. I suppose some evolutionary biologists do recognize their own arguments after all.

Postscript: I have received some extremely positive feedback on these posts responding to BioLogos (see Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3). I want to make it clear, however, that nothing in these posts has been intended to suggest or imply that anybody has acted dishonestly. These posts are simply a response and correction to what I view as inaccuracies and deficiencies in the BioLogos fossil record page.