Education

Education

Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Emory University Professor of Pedagogy Endorses Teaching the Evolution Controversy

An op-ed on CNN.com by Arri Eisen, professor of pedagogy at Emory University’s Center for Ethics, Department of Biology, and Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts, endorses teaching the controversy over evolution in public schools. Under the title “The case for including ethics, religion in science class,” he writes:

High school educators in Wisconsin showed that students who read original texts from Darwin and intelligent-design scholars, and discussing those texts, critically learned evolution better (without rejection of other worldviews) than those taught it in the traditional didactic manner. Teaching potentially controversial science can work if done in an interactive, engaging fashion and in a rich historical and societal context.

(Arri Eisen, “The case for including ethics, religion in science class,” CNN.com (December 15, 2011).)

This is what we have been saying for years. In fact, the big secret of the debate over teaching evolution is that leading science education authorities agree that students learn the science best when they learn about scientific disagreements and are allowed to study scientific topics through critical analysis. Many other science education authorities agree.

In 2000 the National Research Council published a guidebook for teachers, Inquiry and the National Science Education Standards (NSES), which explains:

Inquiry is a multifaceted activity that involves making observations; posing questions; examining books and other sources of information to see what is already known; planning investigations; reviewing what is already known in light of experimental evidence; using tools to gather, analyze, and interpret data; proposing answers, explanations, and predictions; and communicating the results. Inquiry requires identification of assumptions, use of critical and logical thinking, and consideration of alternative explanations.

In 2001, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) co-published the Atlas of Scientific Literacy, which emphasizes that students should “[i]nsist that the critical assumptions behind any line of reasoning be made explicit so that the validity of the position being taken — whether one’s own or that of others — can be judged.” The Atlas further suggests that students “[n]otice and criticize the reasoning in arguments in which fact and opinion are intermingled or the conclusions do not logically follow from the evidence given.”

Likewise, in 2009 the College Board, which issues the SAT exam and Advanced Placement course curricula, released recommended science education standards that strongly emphasize the importance of inquiry-based science learning:

In the course of learning to construct testable explanations and predictions, students will have opportunities to identify assumptions, to use critical thinking, to engage in problem solving, to determine what constitutes evidence, and to consider alternative explanations of observations.

The standards go on to recommend that “[b]oth the evidence that supports the claim and the evidence that refutes the claim should be accounted for in the explanation. Alternative explanations should also be taken into consideration.”

In 2010, we reported on an article in Science titled “Arguing to Learn in Science: The Role of Collaborative, Critical Discourse,” in which education theorist Jonathan Osborne explains the importance of using debate, argument, and critique when teaching science. According to Osborne, there are “a number of classroom-based studies, all of which show improvements in conceptual learning when students engage in argumentation.”

In Osborne’s view, “Critique is not, therefore, some peripheral feature of science, but rather it is core to its practice, and without argument and evaluation, the construction of reliable knowledge would be impossible” (emphasis added). He cites work from sociology, philosophy, and science education showing that students best understand scientific concepts when learning “to discriminate between evidence that supports (inclusive) or does not support (exclusive) or that is simply indeterminate” (emphasis added).

Arri Eisen closes his CNN.com article by saying something else we’ve been saying for a long time:

Clearly, there are a multitude of reasons for America’s polarized politics and decreasing science literacy and innovation that go beyond just teaching science better. But sometimes a little creative wrestling with and engagement in systems and programs that already exist can make a difference.

Again, this is exactly right.

Leading scholars on various sides of this debate agree that science education is in crisis. In 2001, the U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century predicted that “[s]econd only to a weapon of mass destruction detonating in an American city, we can think of nothing more dangerous than a failure to manage properly science, technology, and education for the common good over the next quarter century.”

If there are problems with science education, then obviously they must be linked to the status quo. In this regard, for decades the Evolution Lobby has had near-complete control over science education and has successfully pushed the one-sided teaching of neo-Darwinism in virtually all U.S. public schools.

Given the current state of American science education, obviously something about their approach isn’t working. Why not try something different? Allowing students to weigh the both the pros and cons of modern evolutionary theory would work towards solving those problems. Teaching students the evidence for and against Darwinian evolution would both improve critical thinking skills and increase student interest in science. And whether they ultimately agree or disagree with Darwinian theory, they will understand it better. No matter how you slice it, this inconvenient truth stands: teaching the controversy over Darwinian evolution can only improve scientific literacy.

Let’s close by taking a little inventory. Who supports teaching the controversy over evolution?

- U.S. Supreme Court? Check.

- U.S. Congress? Check.

- American voting public? Check.

- Self-identified liberals, Democrats, and college graduates? Check.

- Leading science education theorists? Check.

- Hundreds of credible Ph.D. scientists? Check.

- Charles Darwin himself? Check.

Many of these groups undoubtedly include evolutionists. Thus, another oft-forgotten secret of this debate is that you don’t have to agree with a view to support its being taught in public schools. Just as ID proponents support teaching the evidence for Darwinian evolution in schools, there are some evolutionists who understand the importance of teaching students both sides of the scientific debate over evolution.

But not all evolutionists feel this way. Despite all of the authorities who stand in their way, certain elite elements in the mainstream media, academia, and the scientific community, who together form the Evolution Lobby, oppose teaching any science that challenges neo-Darwinian evolution in public schools.

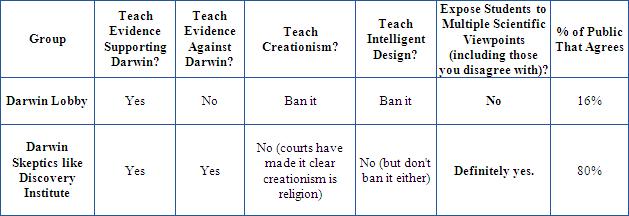

The chart below explains how one of the most basic differences between the Evolution Lobby and ID proponents is that we are comfortable with students learning about views we disagree with, and they aren’t:

Elite Evolution Lobbyists praise inquiry-based science education but jettison that fruitful educational philosophy when it comes to teaching evolution. Critical thinking, skepticism, and consideration of alternative explanations are thrown out the window. In the process, Evolution Lobbyists throw away one of the most promising solutions to the problems facing science education: teach the controversy over evolution.