Evolution

Evolution

Correlation and Causation? Not the Same Thing!

In general, 48 percent of people prefer creamy salad dressings over oily salad dressings. But among those who have never been thrown a surprise party, 60 percent prefer creamy salad dressings.

See correlated.org for further delicious illustrations of the idea of correlation.

Correlation is not causation, and a recent fossil study provides an excellent opportunity to reflect on this fact. The authors appear to be getting set to make a sweeping claim about causation, but backtrack at the end of the article so that what looked to be another evolutionary just-so story ends on a welcome note of humility and skepticism.

According to the early-released PNAS article, “Environmental and biotic controls on evolutionary history of insect body size,” oxygen levels may not have been the primary influence on the size of insects after the early Cretaceous period. (See here for a Geologic Time scale.) Rather, insect body size may have been affected by the presence of birds.

According to the article, small insects have greater maneuverability than bigger ones and, therefore, were subject to favorable selection once birds came on the scene. The authors studied over ten thousand fossil samples of large dragonfly-like insects and compared wingspan with studies on oxygen levels. They concluded that oxygen played a role in body size until the early Cretaceous period. At that point oxygen-to-body-size correlations drop off; oxygen levels rose but insect body size decreased. The authors believe there is strong evidence that the presence of a greater variety of birds is a major contributing factor for this change in correlation.

The idea that factors other than high oxygen levels contribute to large body size is not new. An article from the Royal Society provides an excellent explanation of the variety of factors that could have been at work in determining insect size, including the fact that oxygen may or may not be a substantial contributing factor. As the authors of the Royal Society article point out, some healthy skepticism is called for:

Empirical support for specific mechanisms helps build support for the hypothesis that changing atmospheric PO2 affects insect size evolution, but the multiple plausible pathways in series and parallel make it challenging to determine cause and effect.

Any time an article about fossils, trends, and causation is published, it is important to remember we are dealing with reconstructing historical phenomena. If multiple explanations for a particular historical cause are possible, then each explanation must be held loosely unless new findings indicate otherwise.

The authors of the current study state that they have quantitatively shown how oxygen levels influenced insect body size until the point in Earth’s history when there was a greater influx of birds:

Our quantitative analysis of evolutionary size trends from more than 10,500 measured fossil insect specimens confirms the importance of atmospheric PO2 in enabling the evolution of large body size, but suggests that the PO2-size relationship was superseded by biological factors following the evolution and aerial specialization of flying vertebrates, particularly birds.

Here’s the fine print: The authors looked at the wing size of certain insects, namely flying insects. The insects living on the ground had a slightly different correlation. The authors concede that their fossil samples were limited, always a good caveat to keep in mind when discussing fossils.

Perhaps a more accurate way to report their findings would be something like this:

Our quantitative analysis of evolutionary size trends from measurements of more than 10,500 fossil wing sizes seems to indicate a correlation between body size of aerial insects and atmospheric oxygen levels. This correlation does not hold for the early Cretaceous period, which may be due to several environmental factors including the presence of winged predators, including birds.

This is, admittedly, a little less exciting than claiming that birds are the cause of small insect body size.

The authors assume the presence of predatory birds affected the size of insect bodies. There is not adequate information to conclude that this is a true cause-and-effect relationship. There might be a correlation between bird diversity (and later the presence of bats and other flying carnivores) and insect size, but that does not mean that there is a causal relationship. Given the other environmental factors, which the authors acknowledge are also important factors, there is no way to know.

Here is the just-so part of the story: The authors suggest that small insects were selected because smaller size leads to better aerial maneuverability, allowing the smaller insects to escape predators more easily. This suggestion was made without further explanation, and should be held as a speculative hypothesis, not as a definitive explanation. Even so, there are reasons to question it as the most plausible explanation.

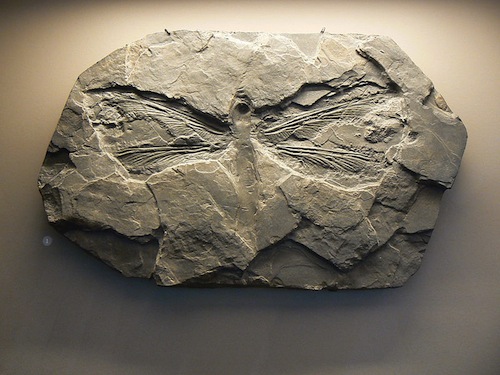

For example, a well-known, fossilized, dragonfly-like insect, Meganeura (pictured above), had a two-foot wingspan. It is often used as an example of large insect body size correlating with high oxygen levels. The catch is that Meganeura is thought to have been carnivorous, preying on other insects. How do we know what effect this insect had on selecting for insect body size? If birds and other predators affected insect body size, how do we account for the presence of insects that prey on other insects? If maneuverability is selected for, how do we know that birds are responsible? Also, how does bird beak size or other physiological factors correlate with the size of the insects?

Interestingly, while the authors go part way down the familiar evolutionary path of constructing just-so stories, they step back in the end. They conclude that there are a variety of factors — such as temperature and altitude — that are possible culprits in explaining the insects’ diminutive body size, which is what we would assume in the first place given the complexity of ecological systems. The authors readily admit that the variety of factors “are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but cannot be tested without more data from Late Cretaceous fossil sites.”

Bottom line: more information is needed to determine the cause of insect body size. In case you were wondering.

Image credit: Wikicommons.