Evolution

Evolution

Natural Selection’s Reach

Image: Mt. Whitney, Tom Hilton/Flickr.

A reader wrote us recently to ask why natural selection can’t extract enough information from the fitness landscape to explain complex features. It all depends on what you think the fitness landscape looks like, and what you think the reach of natural selection is. Dr. Douglas Axe explained the nature of the problem in Science and Human Origins, excerpted below:

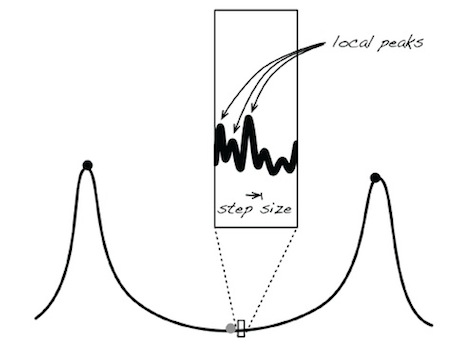

Darwinian evolution is often thought of in terms of journeys over a vast rugged landscape. Each point on this strange terrain represents a possible genome sequence, those possibilities being so staggeringly numerous that real organisms have only actualized a minute fraction of them. The ground elevation at each point corresponds to the fitness of individuals carrying that genome, with the horizontal distance between any two points indicating the degree to which the corresponding genomes differ. In terms of this picture, all of the millions of species alive today are represented by their own points, high up on peaks scattered somewhere across this conceptual landscape (the fact that they are alive demonstrates the quality of their genomes).

Now, wherever a species happens to be, Darwin’s engine tends to move it toward the highest ground it can reach. According to the Darwinian story, that simple tendency to migrate upward has, over billions of years, transported the first primitive genome from its starting point to higher points along millions of diverging paths. The result is the spectacular variety of life forms we see today with a correspondingly wide dispersal of genomes across the vast conceptual landscape.

But there’s something suspicious about this story. It has to do with the wide disparity of distance scales. The scale of the landscape, which is characterized by the extent to which dissimilar genomes differ, is very large by any reasonable calculation. On the other hand, Darwin’s engine moves in steps that can only reach points a tiny distance away from the prior point. In one step it can move a genome to the highest point within this reach, but further progress would require a still higher point to fall within reach once that move is made.

That might happen every now and then, but it would have to happen in an amazingly consistent and helpful way to explain how the enormous distances were traversed from the point marking the first primitive organism to the millions of points marking the great variety of modern life forms.

Let’s put this in more familiar terms. The summit of Mount Whitney,the highest point in the contiguous United States, is just 136 kilometers from the lowest point in North America, known as Badwater Basin. Now, suppose there were an automated vehicle capable of remotely scanning the surrounding terrain within some fixed distance and then moving to the highest point identified by the scan. If the scan radius is greater than 136 kilometers, this vehicle could get from Badwater to Whitney in one scan-and-move operation. But what if the scan radius is one millionth that size? Now the circle that the vehicle ‘sees’ from its current position is about a shoe-length across, with each move being up to half that distance. Considering how uneven the ground is, we wouldn’t expect this nearsighted vehicle to complete more than a few scan-and-move operations before becoming stuck on a rock, maybe half a pace from where it started. Summiting Whitney would be completely out of the question. So the idea that any ability to seek higher ground, no matter how restricted, makes the highest summit accessible turns out to be highly simplistic.

Dr. Axe goes on to explain:

The very same critique applies to Darwinism. Consider that for Darwin’s engine to invent humans from apes, it would have had to work within the severe limitation of a single-mutation scan radius. That is, it would have had to invent humans one simple mutation at a time, with each of these mutations making its possessors significantly more fit than their peers. Contrast this single-mutation reach with the millions of differences that distinguish the chimp and human genomes and we’re back to the impossible trek from Badwater to Whitney. Maybe the genomic landscape is so much simpler and smoother than the Death Valley terrain as to enable Darwin’s engine to cruise upward to exotic destinations on gentle inclines, but why would anyone assume this to be so? Only if experiment after experiment were to prove that remarkable kind of terrain to be the rule should anyone begin to think that something so fantastic might be true.

What is the mutational reach of natural selection in general? It’s very short. For bacteria, our work suggests the reach is only a few mutations at a time. That’s not enough to get a genuinely new function for a protein, let alone a new pathway made up of a handful of proteins, or a metabolism made up of hundreds of proteins. For larger multicellular organisms like us, with slower generation times and smaller populations, the problem gets worse. Much worse.

So unless someone paved a highway to Mt. McKinley that went uphill every step of the way, Darwin’s engine would never get out of Death Valley. But a paved highway isn’t evolution, it’s design.

Cross-posted at Biologic Perspectives.