Education

Education

News Media

News Media

Gotcha! Governor Jindal Avoids Lawyering on TV

Louisiana governor Bobby Jindal signed the Louisiana Science Education Act (LSEA) into law in 2008. The purpose of the law, stated in the text of the law itself, is to “promote students’ critical thinking skills and open discussion of scientific theories.” The law achieves this by granting teachers a conditional right to supplement textbook treatment of evolution, climate change, and other science controversy.

Free up teachers to do what they do best? What’s not to like about that? Well, not everyone is pleased. State senator Karen Carter Peterson recently filed SB 26 to repeal the LSEA, which has been referred to the Senate Education Committee for potential hearings.

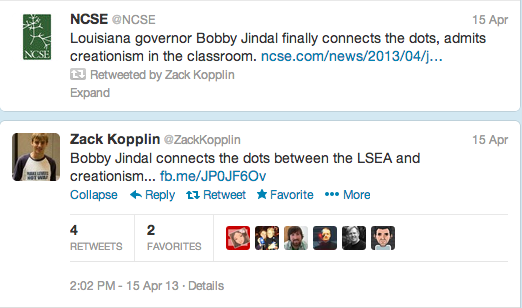

As part of the anti-LSEA public messaging campaign, activist Zack Kopplin has taken to the Bill Moyer and Bill Maher shows, and to Twitter, to argue that despite the plain language of the law, which also disclaims protection for religion, the secret purpose of the LSEA is to put creationist religion into public school science class.

How the LSEA can achieve this bad end using words that call for the polar opposite result is always left mysterious by the LSEA repealers.

Amidst media chatter over secret purposes and threats of repeal, NBC’s Hoda Kotb sat down with Governor Jindal before a live studio audience to talk about education reform in Louisiana. As luck would have it, that talk turned to the subject of the LSEA.

Shortly after the interview, Zack’s anti-LSEA allies at the National Center for Science Education (NCSE) reported that during the interview “Jindal explicitly stated that the so-called Louisiana Science Education Act permits the teaching of creationism, including ‘intelligent design.'” [Emphasis added.]

Another Kopplin ally, James Gill of the New Orleans Times-Picayune, produced a similar reading: “In springing to the defense of the Science Education Act, Jindal does not deny that its purpose is to push creationist dogma.”

To complete the chorus, Zack then echoed on Twitter the NCSE’s reading of the interview and that of Gill as well:

And

The non-lawyers of the repeal camp are constantly giving in the media their legal opinion of the LSEA. And for whatever reason the press just can’t get enough of that. Now in strange unison the repealers publicly chime in on the legal significance of a post-enactment TV interview.

That’s right. This wasn’t pre-enactment floor debate, a conference report or a gubernatorial signing statement. The TV interview is not legislative history. It can’t be used by courts to construct the legislative intent behind the statute, for good or bad. Nor does it reveal how the law is actually being implemented.

What did the Governor actually say during that interview? What words are the critics of the LSEA trying to interpret, exactly? NBC has not yet provided a transcript, so I’ve done the other side a solid by transcribing the key parts of the interview below.

At 9:52 into the video, Hoda asks, “You don’t think creationism should be taught in public schools?” to which Jindal replied:

In public schools, look, our kids are required in science to learn the same curriculum in terms of the ACT and other standardized, national tests. We have what’s called the Science Education Act that says if a teacher wants to supplement those materials, if a local school board is OK with that, if the state school board is OK with that, they can supplement those materials.

Note that Hoda asked Jindal whether creationism should be taught in public schools. “Should” here signifies a question of policy preference, not statutory interpretation. Hoda did not ask whether creationism or any other form of religion is allowed in public schools under the LSEA, or under any law for that matter.

Had she asked such a legal question, first the audience would have audibly groaned and then Jindal would have said, “Let’s confer with the attorney general and executive counsel.” Of course, any version of “talk to my lawyer” makes for bad TV. So mid answer Jindal catches on, shifts gears, and answers the question Hoda asked, appropriate to the setting:

Bottom line at the end of the day we want our kids to be exposed to the best facts. Let’s teach them about big bang theory. Let’s teach them about evolution. Let’s teach them. I’ve got no problem if a local school board says we want to teach our kids about creationism, that some people have these beliefs as well. Let’s teach them about intelligent design. I think teach them the best science. Give them the tools so they can make up their own minds. Not only in science but as they learn about controversial issues whether its global warming or climate change or these other issues. What are we scared of? Let’s teach our kids the best facts and information that’s out there. Let’s teach them what people believe and let them debate and learn that. We shouldn’t be afraid of exposing our kids to more information, more knowledge. Give them critical thinking skills and as adults they’ll be able to make their own and best decisions. [Emphasis added.]

Note that Jindal speaks for himself (“I’ve got no problem …”), as a matter of personal preference, not for the executive branch, the judiciary, the legislature, or any other arm of the state of Louisiana on what the LSEA does as a matter of law.

As chief executives in every field are prone to do, Jindal sets detail aside to cast a vision before his constituents. He is talking about what he’d like to see one day in his state, that he has no problem with local school districts deciding for themselves how best to teach local students.

Like the critics of the LSEA, Governor Jindal is not a lawyer. He delivers no legal memo. However, unlike the critics of the LSEA, Governor Jindal is a Rhodes Scholar with a degree in biology, an experienced politician who knows what his role is and when to stick to it.

(Failing to grasp your role is not just a problem with critics of the LSEA. An astronomer just declared vouchers in Louisiana illegal.)

Jindal’s paean to local over central decision-making is consistent with other planks in his education platform. Of course, reasonable people can and probably should disagree with some aspects of that platform. Teaching actual creationism in public schools is not constitutionally acceptable, if that’s even what he meant. It seems more likely that Jindal, like a lot of other people, used the term “creationism” imprecisely. If he did speak loosely, Darwinists share responsibility for confusing the public, even including a thoughtful guy like Jindal, and taking advantage of a term rendered strategically ambiguous.

Creationism aside, trying to introduce intelligent design in public school science classes, at this stage in the theory’s development, would be unwise, as we’ve often said in the past.

In brief, Jindal was speaking as a politician with an agenda, not as an interpreter of presently existing law. Still, it’s not hard for laymen to read the LSEA right. As far as statutes and regulations go, the LSEA is clear as crystal. (It could be a lot worse.) See for yourself:

A teacher shall teach the material presented in the standard textbook supplied by the school system and thereafter may use supplemental textbooks and other instructional materials to help students understand, analyze, critique, and review scientific theories in an objective manner, as permitted by the city, parish, or other local public school board unless otherwise prohibited by the State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education.

This is a key part of the LSEA. And there is a good reason for it.

Memorization of “science facts” in textbooks for regurgitation on examination — without argumentation and critique prompted by, say, supplemental text — not only bores students and teachers. This old-school form of “learning” also leaves kids with the wrong idea of what science is and how it works, giving them little reason to pursue science into college and career.

With that in mind, the provision above gives teachers a rigid command to teach the textbook followed by a grant of conditional rights to supplement the textbook for the sake of teaching objectively to students the exciting practice of inquiry and critique, of point and counterpoint (i.e., science).

Note that there is no command to supplement the textbook. Within the box of state and local board acquiescence, teachers are trusted to exercise professional judgment on the question of supplementation.

Also notably absent in the text of the LSEA is anything that could reasonably be read to invite creationism or other religious instruction into science class, pace Kopplin et al.

To ensure that only ideologues would misread the LSEA on this point, the text of the law prominently features the following disclaimer of any protection for religion:

This Section shall not be construed to promote any religious doctrine, promote discrimination for or against a particular set of religious beliefs, or promote discrimination for or against religion or nonreligion.

The problem, then, is not the language of the LSEA or with the lawmakers who passed it into law. The problem is with those who, for whatever reason, can’t or won’t read right. Fortunately there is professional help for those who struggle with sentences.

Let’s hope that the critics of the LSEA and other full-time busybodies soon turn their collective attention to self-improvement instead of telling teachers, students, and parents that the law says science class is no place for critical inquiry.