Education

Education

Free Speech

Free Speech

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

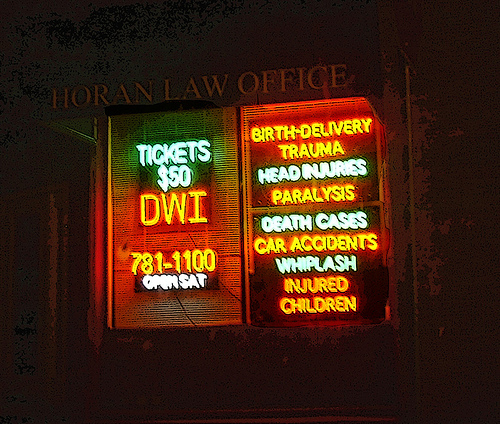

Rosenhouse & Coyne LLP: Internet Lawyers

Did Discovery Institute state that intelligent design (ID) is religion? No, that did not happen, because Discovery Institute doesn’t think ID is religion. What happened was this: last week we gave an interview to a reporter about the case of Ball State University (BSU) and physics professor Eric Hedin during which we basically said BSU can’t lawfully conceive of intelligent design as religion and on that basis proceed to bash it, or as I put it on Friday:

If [Ball State University] administrators want to offer a course bashing intelligent design because they believe it is religion, and because they are hostile to religion, then that motivation when put into effect might constitute to a reasonable observer (e.g., a hypothetical student in the class, as determined by a court) state endorsement of anti-religion, which in turn arguably constitutes a violation of the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

In case you’re wondering what you’re looking at, the above is part of a rough approximation of establishment clause jurisprudence as applied to a hypothetical situation at Ball State University that may turn out to be what really happened rather than a mere hypothetical. It is part of an application of the purpose and effect prongs of the Lemon test within Justice O’Connor’s “endorsement test,” a formulation capacious enough to take into account the subjective motives of state employees, an official stated purpose for the state action if different from the matter of state employee motivation, the actual effect achieved by the state action at issue (i.e., a course offering followed by a certain kind of instruction), and what such an effect would likely signal to a reasonable student observer from a court’s “objective” standpoint.

Does that help clear things up? No? It made things worse? Well, sorry about that. I suppose I should have told you earlier that the test/tests for detecting a violation of the establishment clause is/are only a little more helpful than Justice Potter’s famous test for discerning unprotected obscenity from speech protected by the First Amendment: “I know it when I see it.” If you’re looking for bright line rules in the law, the First Amendment (and its establishment clause in particular) is literally the last place you should look.

As the courts are apt to put it, these religion cases are so circumstance and fact intensive as to be decidable only on a case-by-case basis. You know, because hard cases make bad law, and establishment cases are almost always hard. Never heard that one? Still confused on the whole thing? That’s OK. As I warned last time, this stuff doesn’t get any easier the longer we go.

Now, there’s a down side or two to doing this, to trying to put the law into something like plain English for public consumption. For one, it tends to invite legal opinions and legal advice from permanent Internet dwellers, folks who have no business giving legal opinions and legal advice to anyone, especially not to the general public. See, it’s hard enough as a lawyer to write both engagingly and accurately on the law for a general readership. It must be a shade outside impossible to get it right if you’re a science blogger whose legal training consists entirely of Law & Order re-runs.

As I already mentioned, on Friday I wrote a post that covered in brief what I covered at greater length just now. In response to those 600 kinda concise words, math professor Jason Rosenhouse flung over 1800 words on the wall to basically say I got the law wrong. This in turn triggered evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne to type up another 3200 words or so of “amen” to Rosenhouse. (Perhaps if they’d had more time they would have written shorter letters.) At this geometric rate of growth in wordiness, the three of us will eclipse War and Peace by Easter. To keep that from happening, I’ll just pick a couple of needles from the haystacks that are Coyne and Rosenhouse on the law.

First up, Coyne:

[Y]ou can criticize ID on the grounds of bad science without bashing religion.

Yes, you can. And I, for one, would welcome that scientific critique. The trouble is, Coyne thinks ID is necessarily a religious view, so when he’s critiquing ID, he thinks he’s critiquing religion. This, again, is the sort of mental fact that lawyers tend to care about, particularly when produced by the brains of state employees who then go on to do something dumb, like trying to push religion or anti-religion on students at a state school.

If Coyne was a state school administrator, rather than a private school faculty member, he could offer that course critiquing ID as bad science. That by itself would be no big deal. But if in setting the course up Coyne were to spout off publicly about how ID is really just religion, you better believe the suits would be all over that. And they wouldn’t care at all whether he’s right or not because the governing case law wouldn’t care.

This sort of thing actually happens. BSU’s “Dangerous Ideas” course features a text that criticizes ID on non-scientific grounds while pushing without balance an anti-religious viewpoint, contrary to what BSU’s spokesman recently said on the subject. And now the lawyers are involved.

Next up, Rosenhouse:

If the Discovery Institute wants to sue Ball State for offering a course critical of ID, then they would have to explain to a judge why the purpose or primary intent of the course was anti-religious. Given the many adamant statements by ID’s leading defenders that it is all about science and has nothing to do with religion, they might find that a tough case to make. That BSU’s administrators were hypothetically motivated by anti-religious fervor would be neither here nor there.

True, “ID’s leading defenders” argue that ID is science but, as a matter of law, what these people think and say wouldn’t matter at all in an establishment clause suit against BSU and its administrators. However, the motives, purposes, intentions and other mental states of state employees — especially those of a high-ranking state school administrator — often matter crucially to the resolution of an establishment clause suit. Indeed, these folks are often named specifically as defendants in addition to the institution on whose behalf they act. And sometimes they can be held personally liable in a matter.

Now, what does this hypothetical lawsuit against BSU have to do with Eric Hedin? It is a useful way to remind folks that BSU is a state institution, that it and its employees are state actors for establishment clause purposes, and that BSU administrators must avoid the attribution of anti-religious animus (e.g., those who think ID is religion and then attack it) to the institution itself. With so heavy a burden, state school administrators need to make sure they listen to their lawyers rather than to science bloggers who practice law only on the Internet.