Evolution

Evolution

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Alister McGrath Mistakes Intelligent Design for a God-of-the-Gaps Argument

BioLogos’s concluding article in its series responding to Darwin’s Doubt is by theologian and philosopher Alister McGrath, recently installed as the Andreas Idreos Professor at Harris Manchester College, University of Oxford. I’m a fan of much of McGrath’s writings, but when it comes to intelligent design, there are problems. He has made a long series of inaccurate charges that ID is a “God of the gaps” argument.

Oddly, McGrath’s piece at BioLogos isn’t about Darwin’s Doubt at all. In fact, it doesn’t mention intelligent design. Rather, it’s a transcript from a talk he gave, and someone apparently added the title, “Big Picture or Big Gaps? Why Natural Theology is Better than Intelligent Design,” to the speech. However BioLogos evidently intends McGrath’s piece as a response to intelligent design, so I’ll treat the criticisms there accordingly.

McGrath frames his critique as follows:

My own approach is not to retreat into explanatory gaps. There are those who say (and perhaps I caricature or mis-say what they say), “Well, you know, science can’t explain that. But if there were a god, he could. Therefore, what science can’t explain — that is a good reason for believing in God.” And part of me wants to say, “Yes!” to that. But part of me also wants to say, well, this is not a very good idea, and leaves us bereft of the richness of a vision of God. It kind of implies that you believe in God because of the tiny little holes in somebody else’s explanation, which you think you can explain better in brackets — at least for the time being. For me, it’s not about saying, “Oh look! There’s a gap there, and that’s where God comes in!” No, no, no, it’s about the big picture. That is what makes us think that the Christian faith makes sense of things.

Before we get into this discussion too much, it’s helpful to understand what an early “coiner” of the phrase “God of the gaps,” Dietrich Bonhoeffer, wrote in defining the concept:

…[H]ow wrong it is to use God as a stop-gap for the incompleteness of our knowledge. If in fact the frontiers of knowledge are being pushed further and further back (and that is bound to be the case), then God is being pushed back with them, and is therefore continually in retreat. We are to find God in what we know, not in what we don’t know; God wants us to realize his presence, not in unsolved problems but in those that are solved.

(Dietrich Bonhoeffer, May 30, 1944, Letters and Papers from Prison, edited by Eberhard Bethge, translated by Reginald H. Fuller, Touchstone, 1997.)

By that measure, intelligent design is not in fact a “God of the gaps” argument! I first encountered this comment from Bonhoeffer in Douglas Ell’s book Counting to God, which rightly praised Bonhoeffer’s reasonable argument. ID does not find God, or evidence of design by any intelligent being, in “what we don’t know” but rather “in what we know.” The design inference is fundamentally grounded in our experience-based observations that high levels of complex and specified (CSI) information come only from intelligence. (Note: For simplicity of demonstrating the point, in the rest of this article I refer to high levels of CSI using the simpler term “information,” though I recognize that there are other types “information” out there.) We find evidence for design in what we know about the causes of new information. Intelligent design is a solution to the question of the origin of information.

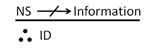

Well, what if ID were a “gaps”-based argument? What might it look like? Something like this:

To put it another way, a gaps-based argument for design would say, “Natural selection and random mutation [which we’ll label “NS”] cannot produce new information, therefore intelligent design [ID] is correct.”

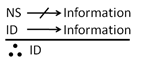

But there’s a big and crucial difference between that argument and the actual case for intelligent design made by ID proponents. An actual argument for intelligent design might be logically portrayed as follows:

In other words, “Natural selection and random mutation cannot produce new information. Intelligent agency, uniquely in our experience, can produce new information. Therefore intelligent design is the better explanation for the information we see in life.” This is not a gaps-based argument. Rather, it’s a positive argument for design, based upon finding in nature the type of information that in our experience only comes from intelligence. Stephen Meyer frames the basic logic of the positive argument this way in Darwin’s Doubt (p. 351):

Major premise: If intelligent design played a role in the Cambrian explosion, then feature (X) known to be produced by intelligent activity would be expected as a matter of course.

Minor premise: Feature (X) is observed in the Cambrian explosion of animal life.

Conclusion: Hence, there is reason to suspect that an intelligent cause played a role in the Cambrian explosion.

You’d never find that kind of logic in a “gaps-based” argument, and thus, there’s a big difference between ID and a “God of the gaps” argument. ID has the necessary positive argument — that intelligence causes high produce CSI — which removes ID from being a “gaps-based” argument. And as we’ll see, there’s a lot more positive content to the design inference that can be discussed.

McGrath’s Odd Formulation of a “Gaps-Based” Argument

McGrath describes a “gaps-based” argument a bit differently from the classical formulation. In the classical criticism, “god” has no positive explanatory value whatsoever, other than to fill in and make up for the failure of some scientific explanation. But McGrath is attacking a slightly different formulation, which, in his description, says “science can’t explain that. But if there were a god, he could.” In saying that a “god … could” explain something, McGrath apparently tries to add a positive component to what he still labels a “gaps-based” argument.” Adding the “god … could” component, changes the dynamic of the case. Now, McGrath is no longer attacking a strictly negative “gaps-based” argument with no explanatory value. Instead he is attacking an argument with some positive explanatory value (though the mere addition of the word “could” doesn’t give us much in the way of positive explanatory value). Is McGrath necessarily justified in rejecting this sort of “gaps-based” argument?

No, not necessarily. Given that BioLogos frames McGrath’s article as a broadside against Meyer’s arguments for intelligent design, let’s say that he’s rejecting the following argument: “Science can’t explain that. But intelligent agency could. Therefore, what science can’t explain — that is a good reason for believing in intelligent design.” This argument, which I am not making, dramatically understates the explanatory power of intelligent design. But insofar as it does resemble the argument for ID, McGrath is unjustified in rejecting it. Why? Because the “could” means that ID has some level of positive explanatory value, meaning it’s not simply a “gaps-based” argument. But just how much positive explanatory value does intelligent design offer? A huge amount.

Thus, another problem with McGrath’s formulation is that he dramatically understates the explanatory power of intelligent design. In Darwin’s Doubt, Stephen Meyer doesn’t just say that intelligent design “could” explain the information in life, but he describes many specific properties of life and the Cambrian explosion which require an explanation that could only be intelligent design. Meyer looks at both the nature of the Cambrian animals themselves, and the nature of their appearance in the fossil record, and finds a whole array of specific features which are only explained by intelligent design. Specifically, Meyer finds that “the cause of the origin of the new animal forms in the Cambrian explosion must be capable of”:

- “generating new form rapidly

- generating a top-down pattern of appearance

- constructing, not merely modifying, complex integrated circuits” (p. 357)

He goes on to say that “any explanation for the origin of the Cambrian animals must identify a cause capable of generating”:

- “digital information

- structural (epigenetic) information

- functionally integrated and hierarchically organized layers of Information” (p. 358)

Let’s see how Meyer provides positive evidence showing that intelligent agents produce those features:

Generating New Form Rapidly:

Intelligent agents have foresight. Such agents can determine or select functional goals before they are physically instantiated. They can devise or select material means to accomplish those ends from among an array of possibilities. They can then actualize those goals in accord with a preconceived design plan or set of functional requirements. Rational agents can constrain combinatorial space with distant information-rich outcomes in mind. (pp. 362-363)

Intelligent agents sometimes produce material entities through a series of gradual modifications (as when a sculptor shapes a sculpture over time). Nevertheless, intelligent agents also have the capacity to introduce complex technological systems into the world fully formed. Often such systems bear no resemblance to earlier technological systems — their invention occurs without a material connection to earlier, more rudimentary technologies. When the radio was first invented, it was unlike anything that had come before, even other forms of communication technology. For this reason, although intelligent agents need not generate novel structures abruptly, they can do so. Thus, invoking the activity of a mind provides a causally adequate explanation for the pattern of abrupt appearance in the Cambrian fossil record. (pp. 373, 375)

Generating a Top-down Pattern of Appearance:

“Top-down” causation begins with a basic architecture, blueprint, or plan and then proceeds to assemble parts in accord with it. The blueprint stands causally prior to the assembly and arrangement of the parts. But where could such a blueprint come from? One possibility involves a mental mode of causation. Intelligent agents often conceive of plans prior to their material instantiation — that is, the preconceived design of a blueprint often precedes the assembly of parts in accord with it. An observer touring the parts section of a General Motors plant will see no direct evidence of a prior blueprint for GM’s new models, but will perceive the basic design plan immediately upon observing the finished product at the end of the assembly line. Designed systems, whether automobiles, airplanes, or computers, invariably manifest a design plan that preceded their first material instantiation. But the parts do not generate the whole. Rather, an idea of the whole directed the assembly of the parts. (pp. 371-372)

Constructing, Not Merely Modifying, Complex Integrated Circuits:

Integrated circuits in electronics are systems of individually functional components such as transistors, resistors, and capacitors that are connected together to perform an overarching function. … [I]n our experience, complex integrated circuits — and the functional integration of parts in complex systems generally — are known to be produced by intelligent agents — specifically, by engineers. Moreover, intelligence is the only known cause of such effects. Since developing animals employ a form of integrated circuitry, and certainly one manifesting a tightly and functionally integrated system of parts and subsystems, and since intelligence is the only known cause of these features, the necessary presence of these features in developing Cambrian animals would seem to indicate that intelligent agency played a role in their origin. (p. 364)

Generating New Digital Information:

Intelligent agents, due to their rationality and consciousness, have demonstrated the power to produce specified or functional information in the form of linear sequence-specific arrangements of characters. Digital and alphabetic forms of information routinely arise from intelligent agents. A computer user who traces the information on a screen back to its source invariably comes to a mind — a software engineer or programmer. The information in a book or inscription ultimately derives from a writer or scribe. Our experience-based knowledge of information flow confirms that systems with large amounts of specified or functional information invariably originate from an intelligent source. The generation of functional information is “habitually associated with conscious activity.” Our uniform experience confirms this obvious truth. (p. 360)

Rational agents can arrange both matter and symbols with distant goals in mind. They also routinely solve problems of combinatorial inflation. In using language, the human mind routinely “finds” or generates highly improbable linguistic sequences to convey an intended or preconceived idea. In the process of thought, functional objectives precede and constrain the selection of words, sounds, and symbols to generate functional (and meaningful) sequences from a vast ensemble of meaningless alternative possible combinations of sound or symbol. Similarly, the construction of complex technological objects and products, such as bridges, circuit boards, engines, and software, results from the application of goal-directed constraints. Indeed, in all functionally integrated complex systems where the cause is known by experience or observation, designing engineers or other intelligent agents applied constraints on the possible arrangements of matter to limit possibilities in order to produce improbable forms, sequences, or structures. Rational agents have repeatedly demonstrated the capacity to constrain possible outcomes to actualize improbable but initially unrealized future functions. Repeated experience affirms that intelligent agents (minds) uniquely possess such causal powers. (p. 362)

Generating New Structural (Epigenetic) Information and Constructing Functionally Integrated and Hierarchically Organized Layers of Information:

After noting that “the role of epigenetic information provides just one of many examples of the hierarchical arrangement (or layering) of information-rich structures, systems, and molecules within animals,” Meyer writes:

The highly specified, tightly integrated, hierarchical arrangements of molecular components and systems within animal body plans also suggest intelligent design. This is, again, because of our experience with the features and systems that intelligent agents — and only intelligent agents — produce. Indeed, based on our experience, we know that intelligent human agents have the capacity to generate complex and functionally specified arrangements of matter — that is, to generate specified complexity or specified information. Further, human agents often design information-rich hierarchies, in which both individual modules and the arrangement of those modules exhibit complexity and specificity — specified information as defined in Chapter 8. Individual transistors, resistors, and capacitors in an integrated circuit exhibit considerable complexity and specificity of design. Yet at a higher level of organization, the specific arrangement and connection of these components within an integrated circuit requires additional information and reflects further design.

Conscious and rational agents have, as part of their powers of purposive intelligence, the capacity to design information-rich parts and to organize those parts into functional information- rich systems and hierarchies. (p. 366)

Meyer concludes that “both the Cambrian animal forms themselves and their pattern of appearance in the fossil record exhibit precisely those features that we should expect to see if an intelligent cause had acted to produce them” (p. 379) He sums his positive argument as follows:

When we encounter objects that manifest any of the key features present in the Cambrian animals, or events that exhibit the patterns present in the Cambrian fossil record, and we know how these features and patterns arose, invariably we find that intelligent design played a causal role in their origin. Thus, when we encounter these same features in the Cambrian event, we may infer — based upon established cause-and-effect relationships and uniformitarian principles — that the same kind of cause operated in the history of life. In other words, intelligent design constitutes the best, most causally adequate explanation for the origin of information and circuitry necessary to build the Cambrian animals. It also provides the best explanation for the top- down, explosive, and discontinuous pattern of appearance of the Cambrian animals in the fossil record. (p. 381)

Thus we see that Meyer identifies a large breadth of features in both biology and the fossil record that are positively and uniquely explained by intelligence. ID is not the arbitrary filling of a gap. There are specific positive reasons for inferring design, based upon our observations of intelligent agents and their products. We use those observations to generate expectations and predictions about what we should find if an intelligent agent was at work in the natural world. When we find those features in the natural world, and conclude that no other natural cause can explain then, we justifiably infer design. This makes ID the opposite of a “gaps-based” argument, because we’re finding in nature specific features — in fact a whole suite of crucial features — which we know from observation only come from intelligence. The argument has multiple strong positive components, and without the positive dimension of the argument, we cannot infer design.

After seeing all of the features of the Cambrian animals and their pattern of appearance in the fossil record that intelligent design predicts and explains, it’s very difficult to accept BioLogos’s and McGrath’s suggestion that Meyer’s extensive positive argument for design is a “God of the gaps.”

Materialism of the Gaps

So why, despite ID’s vast positive explanatory power, does McGrath dismiss ID as an argument based on “gaps”? Because his unwavering default position is to look exclusively to unguided material causes. He assumes methodological naturalism, and privileges material explanations in all circumstances regardless of their explanatory power. In McGrath’s view, even if intelligent design has vast explanatory power, we should still not infer it, because we’re filling a “gap” that ought to be filled by material causes.

In subjecting the scientific enterprise to methodological naturalism (MN), McGrath would force ID to operate under the presumption that natural causes always take precedence, regardless of whether they otherwise seem to fail. This itself is a “gaps-based” argument. McGrath assumes that material causes will eventually fill all the relevant gaps. This is not a real search for the best explanation. It’s a search for the best explanation, provided that the explanation is naturalistic. It’s materialism of the gaps.

ID changes our paradigm, and ID advocates take a different approach. We don’t prejudge the scientific evidence, force-fitting it into the mold of methodological naturalism. Rather, using the principle of uniformitarianism, we make an “inference to the best explanation” — even if that explanation is non-material. If natural causes are the “best explanation” than we appeal to natural causes. If intelligent causes are the “best explanation” then so be it.

This is sound scientific reasoning. I think that Meyer’s inference to design in Darwin’s Doubt would win Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s approval.

Image: Alister McGrath/Wikipedia.