Neuroscience & Mind

Neuroscience & Mind

At the Intersection of Phrenology and Public Policy

My colleague Ann Gauger has an excellent post on the recent PNAS study examining the structural differences between the brains of men and women. I’d like to add a few thoughts.

The researchers studied the brains of men and women using fMRI imaging to measure the size of gyri and other brain regions and to measure several brain tracts that connect regions of the brain. They conclude that while there are some differences in the measurements of men and women, the average differences are dwarfed by the variation within each sex. They conclude that most people are a mosaic of male and female brain structure, with much overlap between men and women. The sexes don’t hew to type, they find.

This research is profoundly insipid work, and it’s remarkable that it was published in a leading science journal. It is irrelevant to any meaningful understanding of human biology, and it’s clear that its political relevance is what got it published.

Am I too harsh? Let me provide a bit of background.

In the 19th century, brain research revealed that some kinds of human activity — speech, movement, and sensation — are consistently associated with proper function of certain discrete areas of the brain. Damage to these brain areas usually causes loss of ability to speak, move, or feel.

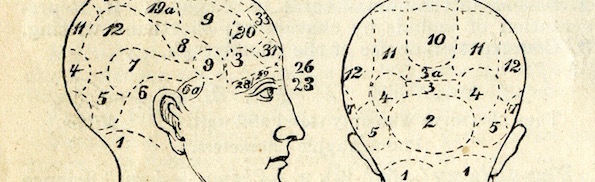

The fact that some human acts depend on highly localizable brain function led many scientists to infer than all human acts — including moral and intellectual actions — had a localizable brain correlate in certain functional “modules” in the cerebral cortex. Scientists believed that the shape of the overlying skull was a reliable indicator of the size of the gyri beneath. In an era before brain imaging was possible, scientists reasoned that minute irregularities in the skull reflected variations in the shape of the underlying gyri of the brain, and the science of phrenology was born.

The phrenologists’ specific neurological thesis was that higher intellectual functions, particularly functions involving moral behavior, were localized in the cerebral cortex, and that the relative size of cortical regions, as reflected in skull shape, was a reliable indicator of intellectual capacity and moral behavior.

Phrenology was enormously influential in the early 19th century, eclipsed in the later half of the century, but had a resurgence in the early 20th century, when the science was used to argue for the relative inferiority of various racial groups.

What is the relation of this 21st century study of gyri to the historical science of phrenology?

The measurement by fMRI of the shape of brain gyri to infer psychological differences between men and women is not like phrenology or similar to phrenology; it is phrenology, done as the original phrenologists wished they could have done it — using brain imaging to directly measure the cerebral cortex, without having to infer brain structure from skull structure.

After a century of neuroscience, we are becoming, at last, better phrenologists.

Of course, the biological differences between men and women are profound, and have nothing to do with the shape of gyri. The important differences between men and women span human biology, psychology, and culture. The differences are too great and too many and too obvious to enumerate, although of course there are many characteristics of men and women that are common to all humanity. Yet to deny the fundamental differences between the sexes, especially the biological differences, is almost a kind of madness. The measurement of gyri notwithstanding, the very existence of humanity depends on the differences between men and women.

This fMRI study of gyri — this modern phrenology — is not just junk science. It is dangerous junk science. It is dangerous junk science because it can and will be used to influence public policy.

The Washington Post:

Lots of folks — well-intentioned and otherwise — like to point out the supposed differences between male and female brains. But it’s time to throw away the brain gender binary, according to a study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Brains can’t really fit into the categories of “male” or “female” — their distinguishing features actually vary across a spectrum.

It’s exciting news for anyone who studies the brain — or gender. And it’s a step towards validating the experiences of those who live outside the gender binary.

This phrenological research should have nothing to do with public policy regarding “the gender binary,” any more than earlier research in phrenology should have had any influence on immigration policy or racial policy. The shape of gyri measured by fMRI is of no more relevance to differences between men and women than the shape of the skull was of relevance to difference between blacks and whites, gentiles and Jews, Anglo Saxons and Slavs, or any of the repugnant uses to which phrenology was applied in its original iteration.

If you want deep insight into the differences between men and women, an fMRI of your spouse is of immeasurably less value than a good dinner conversation. Public policy on sexual differences should be guided by our collective personal religious and secular beliefs, by our daily experiences, by the massive genuine psychology research on the issue, by our literature and history and art and languages that are permeated with reflection on sexual differences, and by our good common sense and judgment and decency.

The obvious purpose of the study — and the obvious reason that this research was published in the leading American biological research journal — is because it fits a narrative about transgenderism that is ascendant in our public square. It is just the latest iteration of dial-a-science: just call and order science to fit the right narrative, and the scientific delivery boy (he, she, or ze) is on the way.

Now the authors and defenders of this article will argue (if called out) that their research discredits phrenology, because it shows that differences in gyral shape are washed out by large variation. But that is a case of special pleading: one does not refute phrenology by doing phrenology. One refutes phrenology by calling it what it is, by refusing to do it, by refusing to publish it in a scientific journal, and by refusing to make public policy based on it.

Image: Chart of Phrenology, Webster’s Academic Dictionary, c. 1895, via Wikicommons.