Evolution

Evolution

Of the Essence — Denton and Aristotle

In an interesting new article, “Aristotelian essentialism: essence in the age of evolution,” Oxford philosopher Christopher Austin argues that in the context of evolutionary developmental biology, the idea of essence isn’t necessarily a contradiction. The argument fits well with Discovery Institute biologist Michael Denton’s case for structuralism.

So what is “essence” in the Aristotelian sense? According to Austin, it is “(a) comprised of a natural set of intrinsic properties which (b) constitute generative mechanisms for particularised morphological development which (c) are shared among groups of organisms, delineating them as members of the same ‘kind’.” It is commonly recognized as that thing without which we cannot imagine a certain kind (for instance, a human without reason). Evolution, which holds that natural selection and random mutation are responsible for all biodiversity, is generally seen as being at odds with the idea of an intrinsic essence.

Austin brings this idea of Aristotelian essence into evo-devo by noting that there are developmental modules that underlie and direct the development of kinds. These fit with his broader interpretation of Aristotelian essentialism — dispositionality, which recognizes cause-and-effect relationships. (A disposition is a property that under conditions X will produce Y.) He appeals to structuralism:

Indeed, in a notable shift from the neo-Darwinian perspective, evo-devo favours a “structuralist” approach, wherein the diversity of organismal development is understood to be underwritten by a drastically less diverse set of developmental modules which themselves constrain and specify the variability of their associated morphological structures according to their own “generative rules.”

Dr. Denton explains that structuralism is “a theory which claims that a lot of the order of the biological world arises from natural law, or what the pre-Darwinian biologists called ‘laws of form’…So a lot of order arises, and biological forms are like crystals and galaxies and atoms. They are part of the changeless order of the world generated by universal laws of form. [Richard] Owen said if we go to another planet, we might find vertebrates…”

But how should one account for these developmental modules? At the very end of his paper, Austin suggests “important areas for further conceptual work,” and one of these is ascertaining how new kinds come about.

For Denton, the “laws of form” are consonant with design.

It goes back to Aristotle’s forms, that the biological world consists, at its base, of a series of what Owen called primal patterns, or basic forms generated by laws of form in nature. So that’s structuralism. It’s not explaining all the order of the biological world, it doesn’t explain adaptation. It’s an attempt to explain the bauplans — the basic plans. Why we have insects, why we have vertebrates…

Structuralism is compatible with notions of intelligent design because the laws of form are part of the laws of nature, and we know from cosmology and astrophysics that the laws of nature are clearly fine-tuned to an extraordinary degree for life on earth. And I think it’s not a secret that a great number of cosmologists have said this fine-tuning gives an impression of design. … Owen, was a very serious Christian in his beliefs about things. He saw the laws of form as part of the laws of God and God’s design imposed in nature itself. So I think it’s absolutely compatible with intelligent design theories.

A preprint version of Austin’s paper is available for free here.

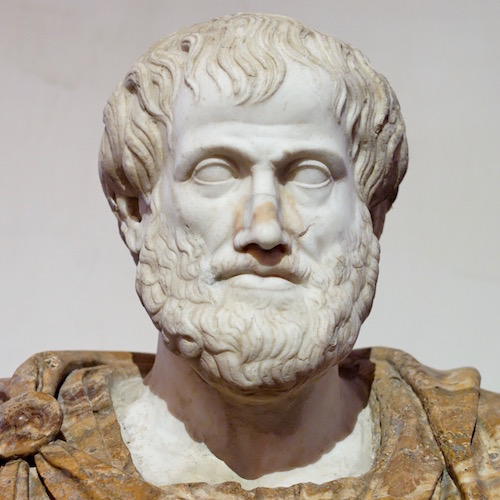

Photo: Bust of Aristotle, after Lysippos [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.