Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Fifty Years Later, Recalling Walt Disney and Scientism

Editor’s note: December 15 marks the 50th anniversary of the death of filmmaker Walt Disney. Discovery Institute Senior Fellow John West is author of the new book Walt Disney and Live-Action, which explores the meaning and making of Walt Disney’s live-action features. In this article, he explores the role of scientism in Disney’s work.

Someone once quipped that Walt Disney harbored “19th-century emotions in conflict with a 21st-century brain.” The characterization was apt.

Disney, who died fifty years ago on December 15, was known for championing traditional morality and promoting nostalgia for a simpler past epitomized by small-town America. At the same time, he was widely recognized as a visionary futurist who enthusiastically embraced the new horizons offered by science and technology.

Disney’s idiosyncratic mixture of moral traditionalism and techno-optimism didn’t always seem to cohere, and it led people to admire him for vastly different reasons. Conservatives embraced Disney for his defense of Judeo-Christian morality, his unrepentant support for American republicanism, his love of free enterprise and entrepreneurship, and his distrust of big government and the welfare state. By contrast, fellow futurists were attracted to Disney’s modernist ideas about urban planning, his exalted view of science and technology, and his utopian visions of human progress.

Although I have a keen appreciation for Disney and his achievements, I admit I’m not one of those who are especially enamored with his techno-optimism. During the last century, we’ve seen far too much destruction arising from the abuse of science and technology for me to believe that science can fundamentally reform the human heart or usher in a utopia. For me, scientific and technological progress is bittersweet. I think Disney was correct to see that science and technology can produce wondrous benefits for humanity. But they also make it easier for humans to accomplish their own destruction — and that darker side of scientific and technological progress was rarely on display in Disney’s projects as a futurist.

Consider his “Carousel of Progress,” a stage show first developed for the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City and later relocated to Disneyland and then Walt Disney World (where it still operates). Featuring “audio-animatronic” robots rather than live actors, the Carousel of Progress depicts the benefits to American society of the rapid technological advances during the first half of the 20th century. The audience meets an iconic middle-class American family at home circa 1900, the 1920s, the 1940s, and the 1960s.

In the 1900s, the family marvels over laborsaving inventions such as cast-iron stoves, gas lamps, ice boxes, and telephones. In the 1920s, the home has been wired for electricity, leading to electric lights, electric sewing machines, refrigerators, toasters, and coffee percolators. In the 1940s, the home adds even bigger and more efficient electric appliances, and by the 1960s, electric appliances have made preparations for previously exhausting holidays like Christmas a breeze.

Each act of this unfolding march of progress is linked together by the song “There’s a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow,” a secular hymn to man’s creativity and his mastery of his environment penned by Richard and Robert Sherman of Mary Poppins fame. The infectious tune boasts that human knowhow can make dreams a reality and usher in “a great, big, beautiful tomorrow”:

So there’s a great, big, beautiful tomorrow

Shining at the end of every day

There’s a great, big, beautiful tomorrow

Just a dream away

Disney’s techno-optimism was also on display in the “Tomorrowland” area in Disneyland, and his planned but never-built “Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow” (EPCOT) in Florida. There is something alluring about the cheerful optimism of these efforts. But there is also something more than a little disturbing. The Carousel of Progress celebrated — apparently without irony — the use of television as parents’ new “electronic babysitter,” and the relocation of grandparents from their children’s homes into segregated communities of seniors.

The “House of the Future” at Disneyland featured modernist, plastic interiors and “irradiated food.” Disney’s vision for his Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow was even more hideous, exhibiting many of the worst features of modernist urban planning: top-down micro-management of every part of life; the artificial separation of where people live and work and play; bleak Bauhaus-style architecture; and the attempt to herd everyone into mass transit.

The visual center of EPCOT was a modernist 30-story hotel that was designed to be seen from miles around, although more traditional architectural forms weren’t completely forgotten. The city’s 50-acre business and shopping district was supposed to include faux buildings and streets patterned after architecture from other parts of the world, all located within a giant, temperature-controlled enclosure — in essence, one great big shopping mall. The narrator of an early promotional film for EPCOT promised: “In this climate-controlled environment, shoppers, theatergoers, and people just out for a stroll will enjoy ideal weather conditions, protected day and night from rain, heat and cold, and humidity.” Disney, who loved nature, who grew up amidst real small towns and farms, and who loved to travel to other parts of the world, planned to dispense with the natural environment in his city of the future. In his new artificial downtown, no one need ever experience the discomfort of the elements. Of course, neither would they experience its joys, including sunsets or summer breezes or raindrops or the songs of birds.

What rescued Walt Disney from being a completely uncritical champion of scientific and technological progress was not his ventures into theme parks or urban planning. It was some of his films. To be sure, his educational productions often promoted the same lop-sided techno-optimism, whether championing nuclear power in Our Friend the Atom (originally prepared for his weekly television show in 1957) or extolling the virtues of mass bombing in Victory Thru Air Power (1943). Fortunately, Disney’s fictional productions displayed more ambiguity.

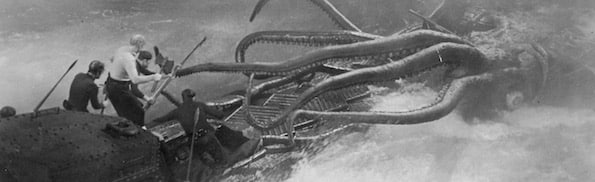

The film in the Disney canon that offers arguably the most explicit warning about the abuse of science and technology is 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), still the definitive cinematic adaptation of the Jules Verne novel of the same name. 20,000 Leagues depicts a supposedly civilized world where international powers employ science and technology for enslavement and death. The film’s Captain Nemo is a twisted genius who ostensibly opposes the misuse of science, but who himself willingly employs science to kill others, even those not directly implicated in the crimes he opposes. At the end of the film, Nemo blows up his discoveries in an iconic mushroom cloud. To audiences in the 1950s, where fallout shelters and duck-and-cover drills were a fact of life, the film’s ending was likely even more powerful than it is today.

Softening the film’s otherwise bleak ending, Disney included a hopeful voiceover before the final credits, repeating the words of Captain Nemo himself from earlier in the film: “There is hope for the future. And when the world is ready for a new and better life, all this will someday come to pass, in God’s good time.” But what ultimately makes 20,000 Leagues so powerful is not those hopeful words, but the film’s unflinching portrait of the human capacity to misuse science, a depiction that even its final words cannot completely obliterate.

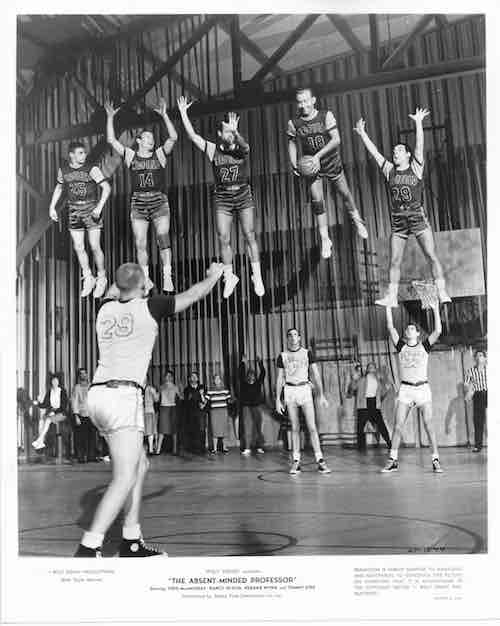

The dangers of science and technology can also be seen in Disney’s comic fantasies, especially The Absent-Minded Professor (1961) and Son of Flubber (1963), two phenomenally popular films starring Disney’s everyman, Fred MacMurray, as Professor Ned Brainard of mythical Medfield College. Brainard invents flying rubber, aka “flubber,” a gooey substance that makes things defy gravity. Brainard is portrayed as a scientific genius, but also as a complete blunderer as a human being. With his single-minded devotion to science, he neglects his human relationships, leading him to miss his own wedding. Brainard is also oblivious to the societal consequences of his research. In Son of Flubber, he runs an experiment that inflicts widespread damage on the rest of his community even while he remains utterly clueless about what he has just done.

Both films highlight how non-scientists try to manipulate scientific discoveries for their own ends, satirizing in particular the behavior of politicians, the military, the IRS, and big business. Professor Brainard himself is shown to be corruptible, misusing his discoveries to take revenge on his romantic rival. For all of their celebration of the creativity of science, these comedies also warned against the pervasive dangers scientific progress can pose. As beneficial as science may be for society, it cannot be left free from social norms, and scientists themselves may not be the best judges of the cultural consequences of their discoveries.

But perhaps Disney’s most scathing indictment of the dark side of technological progress came in a 1952 animated short based on the award-winning children’s book, The Little House, which tells how a beloved house in the country is eventually swallowed up by the encroaching city. Disney’s version of the tale was considerably darker than the original book, with the forces of technological development portrayed by Disney as nothing less than demonic.

The film explicitly attacks the modern slogan of “progress.” While the screen reveals the depressing tenements now towering over the little house, the narrator ironically comments: “Everything was bigger and better, for this was the age of Progress.” Each new wave of “progress” in the film produces ever more nightmarish results, finally resulting in an Inferno of crime and noise and traffic and tawdry 24-hour-a-day neon lights.

Here was a hellish vision of technological progress that seemed to represent the very antithesis of the techno-optimism of EPCOT. Disney may well have viewed EPCOT as an answer to the problems posed by technological progress in the past, showing how science and technology in the future could be harnessed to build better urban environments through all-pervasive master planning. How Disney squared his proposed micromanagement of civic life in EPCOT with his own faith in human freedom, free enterprise, and limited government is anybody’s guess. For myself, I don’t think Disney ever completely reconciled the tensions between his techno-optimism and the rest of his worldview.

But it’s those unresolved tensions that made him all the more intriguing as a shaper of pop culture, and his films all the more worth watching.

All photos: © Walt Disney Company.