Evolution

Evolution

Free Speech

Free Speech

What Would Really Be “Catastrophic” for Science?

Wailing about the threat to science from “deniers” and “anti-science” skeptics is an inescapable feature of public discussions at the moment. Recently, Discovery Institute’s Wesley J. Smith, Jay Richards, Stephen C. Meyer were at the Heritage Foundation to discuss actual threats to science. They nailed a couple of those that deserve a lot more attention than they receive.

It’s a new podcast episode of ID the Future. Listen to it here, or download it here.

First, insofar as the general public perceives, rightly, that viewpoints on science are subject to distorting social, political, and financial pressures, that really is “catastrophic” (Jay Richards’s word). Why would anyone trust the institutions of science, knowing that researchers are not free to follow the truth wherever it leads? Certainly, in the context of the evolution debate, pressures to conform are intense, as we know.

Second, the Discovery team was joined by Marlo Lewis of the Competitive Enterprise Institute who also made a great point. Lewis highlights the problem of science’s dependence on government funding. In the conversation, there’s an interesting clash of opinions between Lewis and Wesley Smith on whether science realistically could be detached from the government. I think Wesely is right that it could not — not entirely.

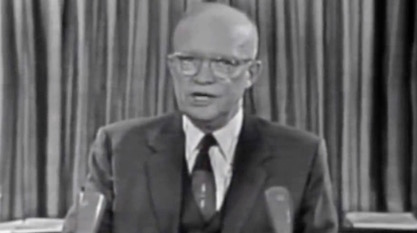

Be that as it may, Lewis cites a telling passage from President Eisenhower’s 1961 Farewell Address. Beside the prophetic warning about the power of the “military-industrial complex,” Eisenhower was concerned about what you might call the scientific-governmental complex.

Of scientific research, he worried, “A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.”

The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present — and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

That prospect, science as the fief of a privileged caste seeking to direct the lives and values of others, pursuing a less-than-transparent ideological agenda, would also call the integrity of the scientific enterprise into question. That too, in Jay’s expression, would be catastrophic.