Neuroscience & Mind

Neuroscience & Mind

What Is Form?

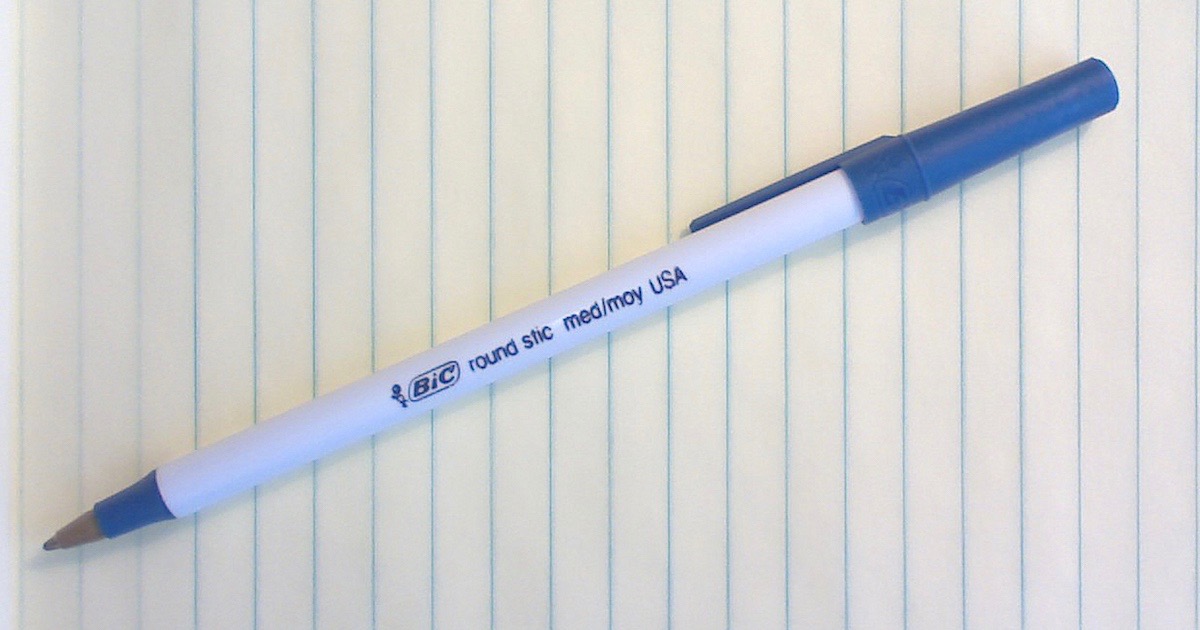

Things that exist — substances — are composites of matter and form. Matter is the principle of individuation in a substance — it’s what makes a thing that thing and not another. Matter is what makes the pen on my desk that particular pen, and not another pen of the same brand and shape and color (of the same form). During change, it is the matter in a substance that persists through the change. The form is different after the change than what it was before. The potentiality for change — the “potency” in Aristotelian lingo — is conferred by the matter of a substance.

The second principle in a substance, besides individuation, is intelligibility. Intelligibility is what can be known about a thing. Intelligibility includes the shape of a thing, and the weight, and the color, and the structure, and anything that can be perceived or understood about the thing. This principle of intelligibility is what Aristotle called form.

The concept of form, and the relationship between form and matter, is of vital importance to hylemorphic metaphysics. Just as matter confers potency to a substance, form confers actuality on a substance. This actuality — act is the Aristotelian term — is what makes something real and specific. Matter is in a sense amorphous (“without form”) — it confers potency and the capacity for change, but in itself it is not real, or at least not fully real as is form. Form makes a thing actual.

All things that exist in nature are composites of matter and form. In fact, this composite, which enables change to take place, is in the Aristotelian sense a good definition of nature. Nature is that which undergoes change, which means that nature is by definition that which is composed of matter and form.

Another way to look at matter and form is that matter limits form. Form as intelligibility is ideal and in a sense unlimited in number. You can have as many instances of a particular form as you can conceive. There is no limit to the number of six inch Bic ball point blue pens that can be conceived. Matter limits form, making form individual, belonging to one individual thing and not to another. The matter of the pen on my desk limits the “six inch Bic ball point blue pen” form to the pen on my desk.

Philosopher Ed Feser provides a useful example of form and matter in a circle drawn in ink on paper. The circle is round, but it is actual in a limited way — imperfectly round, in this location at this specific time. The circle is by nature more or less round, and thus actual, and limited in its roundness, and thus potential. The circle has only partially actualized its potential for roundness, yet has fully actualized its potential for imperfect roundness in a specific place and time. The drawn circle is thus a composite of matter (potency) and form (actuality). In this way, every actual thing in nature is a composite of matter and form, and thus a composite of potency and act.

Matter and form are intrinsic principles of the existence of a thing. Matter is the potency and that which persists through change, and form is the actuality and that to which something changes. In terms of Aristotle’s Four Causes, matter and form are the material and formal cause of a thing being that which it is. There are, in addition, two extrinsic causes that characterize a thing: efficient and final causes.

It’s useful here to compare this concept of things that exist in nature with the materialist perspective. Materialism, which (to the extent that it provides metaphysical explanations at all) defines matter as extension in space, offers no coherent explanation as to how change in nature is possible, how a thing can be intelligible, and a host of other essential aspects of reality. Materialism is an impoverished perspective on nature, and it creates, rather than solves, problems in metaphysics and science.

There are many more aspects of form that are important — substantial and accidental forms, forms of living things, the relationship between form and existence, the question as to whether pure forms can exist, and the role forms play the mind — in perception and understanding. But those are subjects for another time.

Photo: Bic pen, by Dfass (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.