Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

DNA, Information, and Aristotle’s Nobel Prize

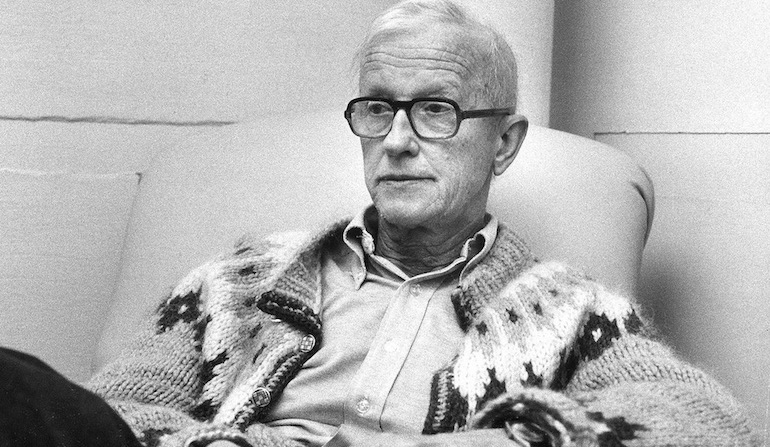

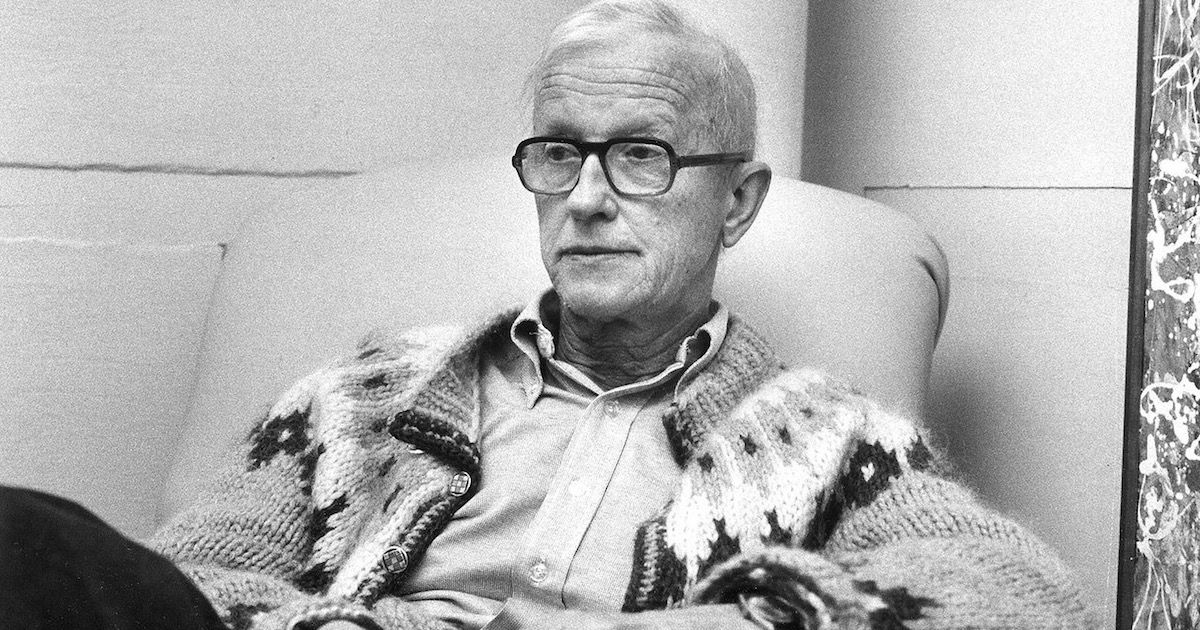

Max Delbrück (1906-1981) was a biophysicist and Nobel laureate who made seminal discoveries in the DNA-based replication of viruses. He was a pioneer in molecular genetics, and, unlike so many scientists of today, he had a profound understanding of the philosophical underpinnings of modern biology. He was a life-long student of Aristotle, and in his Nobel acceptance speech he credited the Stagirite with remarkable prescience of molecular genetics.

Delbrück:

At the very beginnings of science the striking dissimilarities between the behavior of living and nonliving things became obvious. Two tendencies can be discerned in the attempts to arrive at a unified view of our world. One tendency is to use the living organism as the model system. This tendency is exemplified by Aristotle. For him, the son of a physician and the keen observer of many forms of life, it was obvious that things develop according to plans. Every animal and plant is generated in some definite way, runs through a cycle of development in which it unfolds its inherent plan, and succumbs to death and decay. For Aristotle, this very obvious feature of the world which surrounds us is the model for understanding our (sublunar) world.

In antiquity, there were two views of how the gametes transmitted life. Many pre-Socratic philosophers believed that miniature replicas — homunculi — of the parents were incorporated in the sperm. Aristotle insisted that the transmission of life was a transmission of form, not of matter. The transmission of life from parent to child was the transmission of a plan, which could be understood as a principle incorporated in matter but ontologically distinct from matter.

In a paper written shortly after his Nobel lecture, Delbrück endorsed Aristotle’s anti-reductionism and noted the “essential beauty” of a living organism, understood as a complete individual:

Just so one should approach the study of any animal with reverence, in the certainty that any of them are natural and beautiful. I say “beautiful” because in the works of nature and precisely in them there is always a plan and nothing accidental. The full realization of the plan, however, that for which a thing exists and towards which it has developed, is its essential beauty. Also one should have it clearly in mind that one is not studying an organ or a vessel for its own sake but for the sake of the functional whole. One deals with a house, not with bricks, or wood. Thus the natural scientist deals with the functional whole, not with its parts, which as separate entities have no existence.

The author at Bioperipatetic notes:

Biogenesis, the development of entire organisms from strands of DNA containing the “plans” for all possible protein molecules needed to create and to continuously sustain the life of a given species, is a dramatic case of emergence. Life cannot be reduced to the molecular properties of DNA alone. What is needed is to explain the dynamics of biogenesis and the incredibly intricate coordination and synchronization of complex activities within each individual living cell that bring about the emergence and maintenance of life itself. For a dramatic presentation of the profound complexity, and intricate orchestration of life processes within each of the 120 trillion cells in each of our bodies, view the 7-part series: Secret Universe: The Hidden Life of the Cell.

Bioperipatetic goes on:

Soon after delivering that Nobel lecture, Max Delbrück, in 1971, wrote a paper in homage to Aristotle’s brilliant theory, entitled “Aristotle — totle — totle” (and later in a personal letter to a dear relative with the title: “How Aristotle Discovered DNA.”), recommended that Aristotle be awarded the Nobel prize in biology for his discovery of the principle underlying DNA, i.e., a plan as the causal principle for the creation of a new organism. Thus the plan is used to guide the future development of the new born, but is itself unchanged in the process.

It is in the form written in the DNA, rather than in the deoxyribonucleic acids themselves, that the plan for life is encoded and transmitted. This insight derives from Aristotle, and was confirmed with astonishing accuracy by Watson and Crick’s discovery of the genetic code in DNA in the early 1950s.

This formal transmission of life — this in-form-ation encoded in DNA — reveals that it is Intelligence, not matter, that transmits life from parent to child. For that insight, Delbrück notes with due admiration for the philosopher who first understood that information was the fundamental principle of life, Aristotle undoubtedly deserves a trip to Stockholm.

Photo: Max Delbrück, by Dr. Ernst Peter Fischer via Wikicommons.