Evolution

Evolution

Alfred Russel Wallace: A Life in Science, Rediscovered

Editor’s note: We are delighted to welcome the new book Nature’s Prophet by science historian Michael Flannery with a series of excerpts. Professor Flannery is a Fellow with Discovery Institute’s Center for Science & Culture. Nature’s Prophet is currently on sale here for $26, a substantial saving from the list price of $44.95.

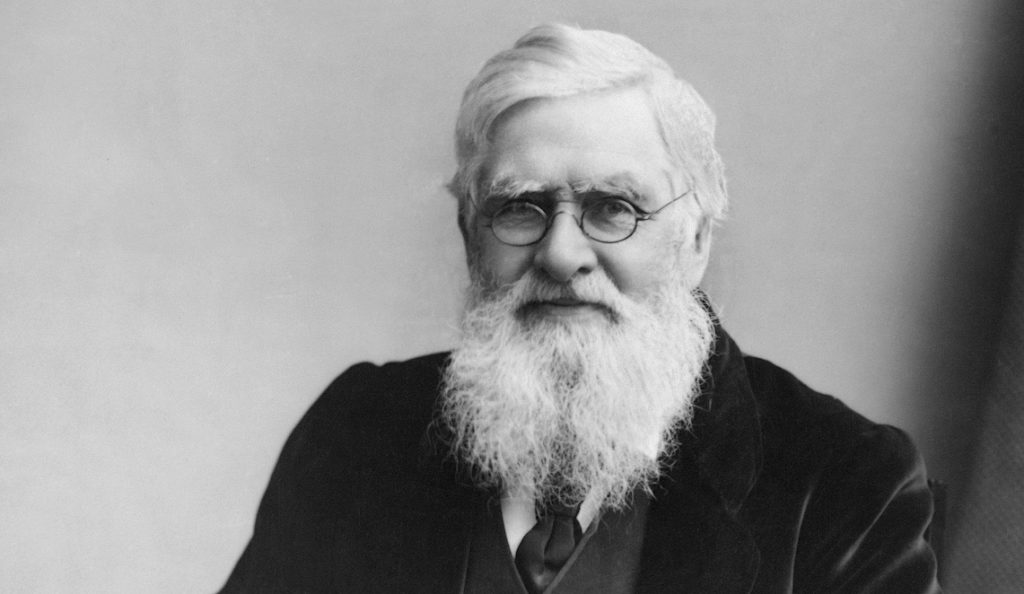

Despite the notability of Alfred Russel Wallace in his own day, he remains a comparatively obscure figure in the history of biology. Standard college textbooks on the subject barely mention him. It is, therefore, likely that a considerable segment of the reading public needs some introduction to a man inextricably intertwined with the British naturalist who needs no introduction at all — Charles Darwin.

Despite the notability of Alfred Russel Wallace in his own day, he remains a comparatively obscure figure in the history of biology. Standard college textbooks on the subject barely mention him. It is, therefore, likely that a considerable segment of the reading public needs some introduction to a man inextricably intertwined with the British naturalist who needs no introduction at all — Charles Darwin.

Born on January 8, 1823, in Usk, an obscure English-Welsh border town, Wallace had little formal schooling, learned surveying from his brother William, taught himself botany and entomology, and with his new-found beetle collecting friend, Walter Henry Bates (1825-1892), became captivated by the wonders of nature. When he read the anonymous Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation in 1845 (now known to have been written by Robert Chambers [1802-1871]), a book that sparked his passion to unlock the secrets of transmutation, he went off with Bates to explore South America from 1848 to 1852. Unfortunately, during his journey home, the ship, Helen, loaded with flammable copaiba, balsam, and rubber, caught fire, destroying all his private collections of birds, insects, live animals, notes, sketchbooks, and just about every record of his four years in South America.

Despite his losses Wallace managed to publish two books in 1853 about his time on the South American continent: Palms of the Amazon and Rio Negro and A Narrative of Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro. His book on palms was published at his own expense and had a small print run of 250 copies. It received a favorable review in the Annals and Magazine of Natural History, but privately, leading scientists like botanist Sir William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865) and fellow explorer-botanist Richard Spruce (1817-1893) were less impressed. His Narrative fared little better. Although 750 copies were published, one-third of them remained unsold nearly a decade later.

To Redeem a Failure

In 1854 Wallace decided to redeem his earlier failure in South America by traveling to the Malay Archipelago (today known as Maritime Southeast Asia). As Wallace himself put it, there, “I was to begin the eight years of wandering throughout the Malay Archipelago, which constituted the central and controlling incident of my life.” It was “central and controlling” because during this expedition (ca. March 25, 1858), Wallace sent Darwin a remarkable letter, “On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart from the Original Type.” Darwin, sitting comfortably at Down House with his voyage on the H.M.S. Beagle long behind him and his epoch-making evolutionary theory still languishing in manuscript, received the letter on June 18 and was stunned: “I never saw a more striking coincidence,” he wrote Charles Lyell on June 18, “if Wallace had my M.S. sketch written out in 1842 he could not have made a better short abstract! Even his terms now stand as Heads of my Chapters.”

What should they do? Do nothing and Darwin risked being preempted by Wallace; release his own version without mention of the letter, which Wallace had sent from Ternate in the Malay Archipelago, and risk being called out by Wallace for plagiarism. After some mutual consultation among Darwin and his confidants, Charles Lyell (1797-1875) and Joseph Hooker (1814-1879), the three decided to read selections of Darwin’s work along with Wallace’s letter at the next meeting of the Linnean Society. Thus, on July 1, 1858, the modern theory of descent with modification by means of natural selection was first unveiled. Of course, on the other side of the earth, it was impossible to consult with Wallace in advance. When he did learn of what transpired Wallace was elated. In the highly stratified class system of Victorian England, Wallace, a man of modest birth and modest means, was given an opportunity of a lifetime — entrance to the elite circles of British society through one of the most prestigious scientific organizations in London. Writing home, Wallace declared, “This ensures me acquaintance of these [important and influential] men on my return home.” Interestingly, as if to emphasize his satisfaction with the way his theory was presented and to allay any concerns that he might have felt otherwise, Wallace added in the later abridged version of his autobiography, “Of course I not only approved, but felt that they had given me more honour and credit than I deserved, by putting my sudden intuition — hastily written and immediately sent off for the opinion of Darwin and Lyell — on the same level with the prolonged labours of Darwin.”

Debut at the Linnean Society

Wallace’s debut at the Linnean Society meeting transformed the wandering naturalist into an important figure within British science. Until then Wallace was known among collectors largely through his intermediary for those sales, Samuel Stevens (1817-1899); and while his earlier Sarawak Law paper caught the attention of a few, it was by and large ignored by Darwin. The Linnean Society reading of Wallace’s paper was significant. In fact, the association with Darwin’s theory of natural selection tended to make Wallace’s ideas appear more closely related than they really were, a point that will be addressed in more detail later in this book.

Nevertheless, the unveiling of the modern theory of evolution by means of natural selection was fortuitous for both men. Wallace received the renown he could never have achieved on his own, and Darwin now had the impetus to finally release his ideas to the public, which he did in November 1859 with Origin of Species. It transformed both their lives. On a personal level Wallace and Darwin remained cordial throughout their lives, and Darwin was so appreciative of his younger colleague’s magnanimity that he even led a successful campaign to obtain a government pension of £200 per year for Wallace in recognition of his service to science and the nation.

By the time of Darwin’s death on April 19, 1882, Wallace had done much to earn the pension awarded him. His years traversing Maritime Southeast Asia from March 1854 to March 1862 are chronicled in The Malay Archipelago (1869), one of the few works of its kind in continuous print to this day. This masterpiece, regarded by many as perhaps the greatest work of its kind in the English language, influenced the literary work of such notables as Joseph Conrad (1857-1924) and Somerset Maugham (1874-1965). His Geographical Distribution of Animals (2 vols., 1876) has earned him the title “father of modern biogeography,” and a professional award in that field bears his name. Ever sensitive to the interplay of climate, geography, and the nature and diversity of biological life, Wallace wrote Tropical Nature (1878) to clarify and dispel many erroneous ideas that had grown up around what really composed the characteristics of the tropical zones as distinguished from the temperate zones. Although ostensibly written to address Darwin’s assertions concerning coloration in animals “explained” by his theory of sexual selection, it has perhaps been more significantly identified as anticipating Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in its concern for the fragility of tropical habitats and the intrusions of European civilization upon them. Wallace’s pathbreaking book on island ecosystems, Island Life (1880), was dedicated to Joseph Hooker. Darwin considered this the best of all his books, and it likely served as the catalyst for the senior naturalist’s petition for Wallace’s pension.

A Comparatively Little Known Figure

This is no more than a highlight of Wallace’s scholarship and life. Altogether he published twenty-two books, more than 500 scientific articles, and many others on a range of social, political, cultural, and metaphysical topics. By the time of his death at the age of ninety, Wallace had amassed an impressive array of awards: Medal of the Royal Society (1868), the Société de Géographie’s Gold Medal (1870); the Founder’s Medal of the Royal Geographical Society (1892); Gold Medal of the Linnean Society of London (1892); election to the Royal Society (1893); the Copley Medal of the Royal Society (1908); and the Order of Merit (1908) to name a few.

But these accolades beg the question touched on earlier, why is Wallace today a comparatively little known figure next to Darwin?

Photo: Alfred Russel Wallace, by London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company (active 1855-1922) (First published in Borderland Magazine, April 1896) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.