Neuroscience & Mind

Neuroscience & Mind

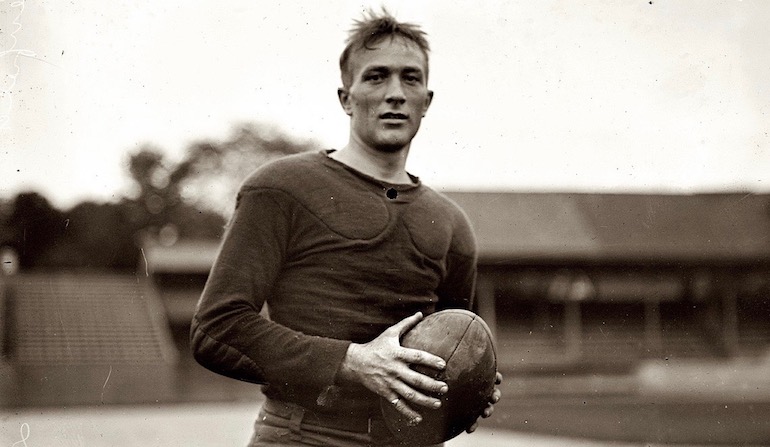

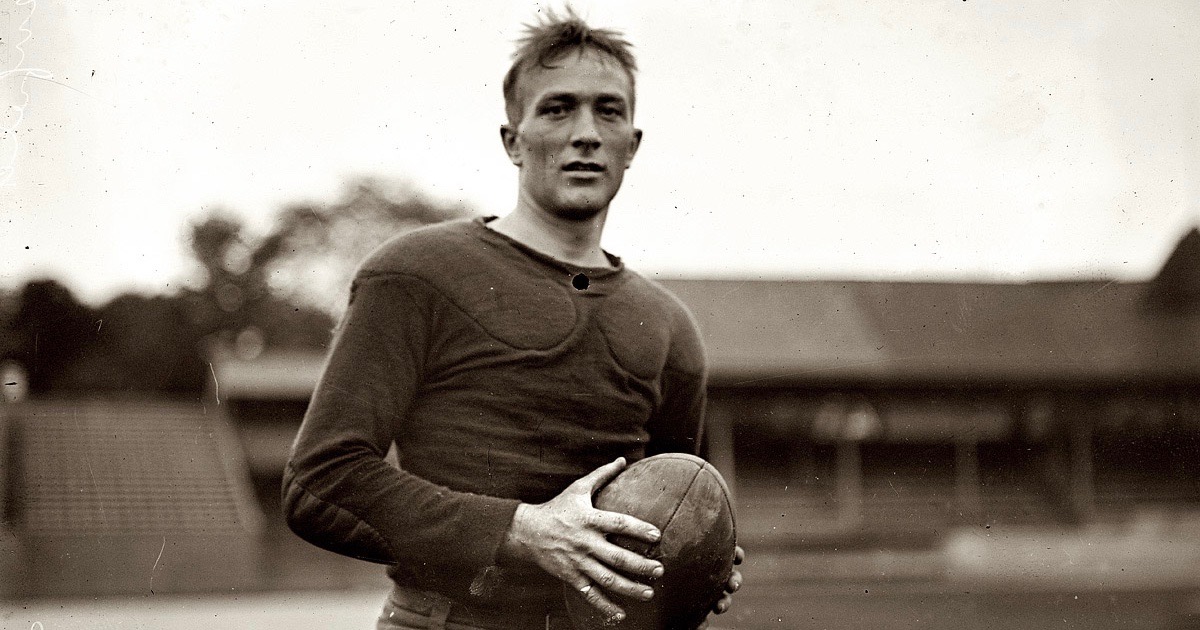

Neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield on Free Will

Materialists claim that neuroscience has demonstrated that free will is an illusion. Yet in fact, there is strong support for the reality of free will from neuroscience, in addition to decisive philosophical and logical arguments for free will.

For a philosophical example, consider that affirmation or denial of free will is a proposition, which is a statement that may or may not be true. But matter has no truth value — propositions aren’t material things. Matter just is; it is neither true nor false. Thus, when a materialist claims that material causes preclude the possibility of free will, he is also claiming that his own opinion cannot be true (or false). Denial of free will on the basis of materialistic determinism is self-refuting.

A Pioneer in Epilepsy Surgery

But, as noted, there is strong scientific evidence to support free will as well. Some of the earliest evidence came from neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield, who was the pioneer in epilepsy surgery in the mid 20th century. Penfield operated on over a thousand epilepsy patients while they were awake (under local anesthesia), and he stimulated their brains with electrodes in order to identify epileptic regions for surgical resection. He carefully recorded their responses to stimulation. In his book Mystery of the Mind,* Penfield noted:

When I have caused a conscious patient to move his hand by applying an electrode to the motor cortex of one hemisphere, I have often asked him about it. Invariably his response was: “I didn’t do that. You did”. When I caused him to vocalize, he said: “I didn’t make that sound. You pulled it out of me.” When I caused the record of the stream of consciousness to run again and so presented to him the record of his past experience, he marveled that he should be conscious of the past as well as of the present. He was astonished that it should come back to him so completely, with more detail than he could possibly recall voluntarily. He assumed at once that, somehow the surgeon was responsible for the phenomenon.

Penfield never encountered a patient who, with stimulation of the brain, thought that he (the patient) had willed it. The patient could always distinguish between acts he willed himself and acts imposed on him by the surgeon’s electrode. My own experience (much more limited than that of Penfield, as I am not primarily an epilepsy neurosurgeon) has been the same. Patients can always distinguish evoked responses from voluntary willed responses.

No Counterfeit Will

Penfield marveled that he could stimulate all manner of movement and sensation and memory, but he could never evoke agency. He couldn’t stimulate the sense of will — he couldn’t produce a counterfeit will in the conscious patient by stimulation of the brain.

Penfield concluded that this meant that the will (he called it the “mind”) was not in the brain, or at least not in any part of the brain that he could stimulate, and that the will was not a physical thing. The will was free, in the sense that it could not be evoked by material means.

Penfield began his career as a strident materialist. He ended it as a passionate dualist — the title “Mystery of the Mind” was largely the expression of his amazement that there was a scientifically demonstrable duality to the mind. He affirmed, by pioneering surgery on the brains of over a thousand conscious patients, that man is a composite of material and immaterial mental abilities.

Neuroscience provides strong evidence for mind-brain dualism, and science dovetails nicely with the compelling philosophical demonstrations of the reality of free will. There is no credible evidence in neuroscience that would lead an objective scientist or reader to conclude that free will is not real.

The denial of free will is an ideological bias, not a credible scientific or philosophical conclusion.

Photo: Wilder Penfield in 1911 as a student at Princeton, by Bain News Service [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.