Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

A Watch on a Heath — But What a Watch!

William Paley was an English clergyman who at the beginning of the 19th century published a book called Natural Theology. His book was extremely popular, finding a wide readership. In fact, Charles Darwin was very taken by it. He read it with enthusiasm and was convinced by its arguments for a long time. When he developed his own theory he took Paley’s style of argumentation as his own. Paley fell out of favor; Darwin’s star rose as Paley’s sank.

Now Paley is mostly remembered for his analogy of a watch on a heath. Suppose you were walking along and you came upon a watch lying there. What would you suppose was the source of that watch? Would you think it had grown there? Or would you think someone had made it? Paley argued that the watch was designed because it had all the hallmarks of designed objects. He then went on to argue that living things also had all hallmarks of designed objects.

I myself have not yet read Natural Theology. But I think I will. Stephen Jay Gould had a sort of a love/hate relationship with the book. He gave it backhanded compliments, saying that Paley had a skill for argumentation — he knew how to take apart the arguments of his critics. But Gould didn’t like his conclusions.

Why do I bring up Paley and his watch on the heath? One of the criticisms that intelligent design has faced is that we are too mechanistic: that we think of the nature of life itself as being like little machines but that life is nothing like a machine, it is a different category altogether. Watches are machines and watches are made by human beings. It’s easy to see that when you look at them — they have mechanisms, they have springs, they have gears. We recognize they have a designer because of those features, whereas we have no springs, no gears, no obvious mechanisms that look like human-made things.

An Art Form

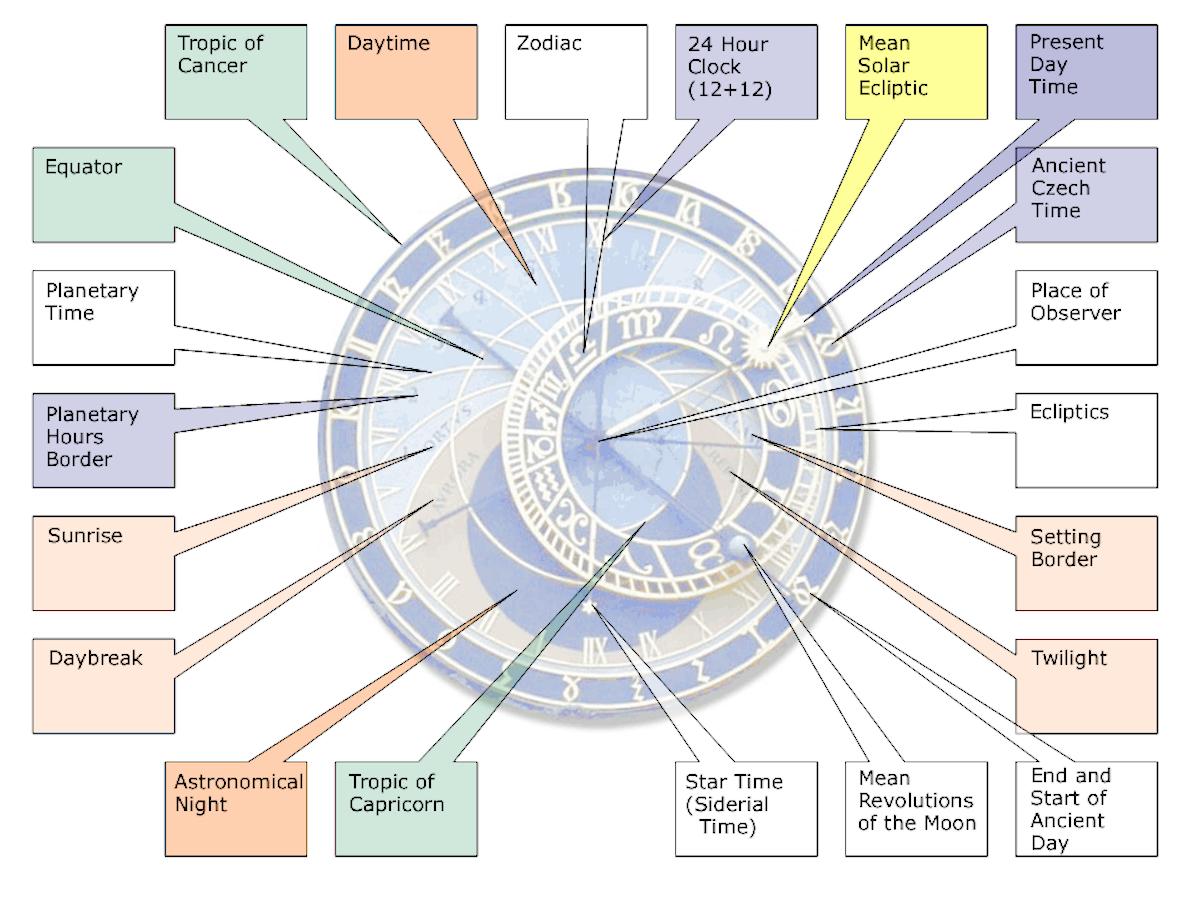

This had been on my mind when I went recently to the city of Prague, not expecting to find an answer. There I found Prague’s astronomical clock, the oldest still-working astronomical clock in the world. It is truly phenomenal. In the Middle Ages, clocks like these were an art form. The clock had to show not only the time of day but the time of year, the sidereal time of the stars, the time of sunrise and sunset as it changed through the year, the phase of the moon, the astrological time, the lunar time — all of those things on one clock. I’m giving you a close-up of the face of the clock, a picture of the clock as a whole, and then a diagram indicating where the information is on the clock’s face.

Photo credit: Steve Collis from Melbourne, Australia [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Now assuming you were to find a clock face like this, only on a smaller scale, lying on the heath, would you assume it was designed? In fact, it’s not just a mechanism that tells you that it’s designed. It’s the information written on the face of it. It’s the information that conveys that the designer understood the way the moon and sun are related to the earth and the way that the stars appear to circle the pole. The people of the Middle Ages had a profound understanding of that movement of the stars, sun, and planets in the sky even though they may not have understood the actual orbits. They understood how they are related in the sky so they could predict where they would be at any given point. That is all portrayed on this one surface.

Not Just a Mechanism

That’s information — intense information. It’s not just a mechanism, although it’s an elegant mechanism for conveying information. If I were to find such a thing I would certainly be convinced that whoever made this was not only ingenious in designing mechanisms but was also quite reflective about the nature of what was going on in the night sky. The sophistication showed me something about the sophistication of the people of the time, some 600 years ago when this astronomical clock was made.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

This clock taught me about what their minds understood, what they were capable of. So when we find sophisticated information embedded in our genomes, what does it tell us about the maker of our genomes? For example, when we find codes being used in multiple frames, that’s efficient use of storage, and perhaps more that we don’t know. What does it mean?

Who Directs That Traffic?

What do I mean by frame? We have a few examples in English.

“Able was I ere I saw Elba.” Read forward and backward it is the same. Now imagine a code that said “We need eggs” read forward in one frame, and “oot nocaB” in reverse (read it backward) in another frame of the same piece of DNA. Then just for laughs suppose you could start another sentence on the “a” in “Bacon” that said “Coffee please.” That would be three genes in one stretch of DNA. It can happen, but it is rare.

Or there are transcripts (RNA copies made from DNA) that start on one chromosome and finish on another! Who directs that traffic?

Another information-rich system to consider is an elegant design (seen from one point of view, or a mystery from another): many genes in eukaryotes (organisms whose cells have organelles like nuclei and mitochondria, which includes us) are interrupted by insertions of non-coding DNA called introns. Why? Well, you can think of it this way: with 1 gene and 3 exons (2 introns) you have the possibility of getting (1, 2, 3, 1+2, 1+3, 2+3, 1+2+3) 8 different proteins. This comes in handy for increasing diversity between species even if they share pretty much the same DNA.

If I thought about it some more I could probably find more examples of sophistication in our genomes. Moonlighting proteins? Organization of chromosomes inside the nucleus? I think I’ve said enough. How do you read our genomic astronomical clock?

Photo at the top: Prague astronomical clock, by Andrew Shiva, via Wikimedia Commons.