Evolution

Evolution

Darwinism: Past, Present, and Future

Ann Reid, executive director of the nation’s leading Darwin lobby, the National Center for Science Education (NCSE), has insisted in an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, “Goodness knows the science is settled, too. No credible scientist doubts that evolution is the theoretical and practical core of biology, with more evidence emerging from a rich array of research fields with every passing year. Claiming that evolution remains an open question is as scientifically preposterous as suggesting that the jury is still out on whether matter is made of atoms.”

Make no mistake here what Reid means by evolution is neo-Darwinian evolution with all its manifest assumptions. It’s an old refrain heard many times over by her predecessor, Eugenie Scott. And if the NCSE isn’t proof enough, just ask Richard Dawkins who insists that the neo-Darwinian paradigm encapsulated in the mantra-like word evolution “is a fact. Beyond reasonable doubt, beyond serious doubt, beyond sane, informed, intelligent doubt, beyond doubt evolution is a fact” (see The Greatest Show in Earth, p. 8).

Doubts on the Rise

But amidst all this chest thumping over neo-Darwinian certainties, doubts are unmistakably on the rise. Most interestingly they seem to be expressed in ways that were unthinkable among Darwin’s previous generation of followers. One thinks of the unbridled celebrations at Darwin’s centennial publication of his Origin of Species. The largest was hosted by the University of Chicago, November 24-28, 1959, and it drew 2,500 participants with almost 250 delegates from 189 colleges. Many of the “synthesizers” of modern genetics with Darwinian evolution were there: George Gaylord Simpson, Theodosius Dobzhansky, Ernst Mayr, and the grandson of Darwin’s Bulldog, Julian Huxley. Betty Smocovitis could say in 1999, “that it outshone — and arguably may still outshine — all other scientific celebrations in the recent history of science.” When Dobzhansky declared in 1973 that “nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution,” he was saying what virtually everyone was thinking — and saying in different ways — during those momentous fall days 14 years before. The future was bright and hardly in doubt.

In that context a recent collection of essays, compiled in an anthology titled Darwin in the Twenty-First Century: Nature, Humanity, and God, caught my attention. They demonstrate that Smocovitis’s claim remains true; the centennial celebration would know no equal. Here’s why. These 16 chapters were the products of conferences held at the Gregorian University in Rome and at the University of Notre Dame to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Most interesting of all is the last essay by a noted historian and philosopher of biology, the late Jean Gayon, “What Future for Darwinism?” Against the centennial celebration, the question itself stands out as one that certainly wasn’t to be seriously asked in Chicago.

“An Uncertain Future”

But it appears that fifty years have made a difference. Gayon’s prognostications for Darwinism are a bit unclear, but he admits that the essay itself aims at “exploring an uncertain future.” This is most interesting coming from a scholar whose career largely defended the neo-Darwinian paradigm (see, for example, his Darwinism’s Struggle for Survival). For Gayon, Darwin’s basic principles of common descent, modification and variation of species, and natural selection “will remain a definitive part of evolutionary theory.” He predicts “a proliferation of models” that will “flesh out” and even reformulate those principles. He also predicts that Darwinism will spread over the human sciences, stimulating “important convergences and hybridizations,” though he doesn’t explain what those might be. While evolutionary biology is on the defensive (the evo-devo debate, symbiotic ecosystems in geobiology), in the human sciences, Gayon assures us, it is on the offensive. Then, most intriguingly, after pumping up “universal Darwinism” and its prospects, he says, “I predict that universal Darwinism as a philosophy of nature (biological and human nature) will die one day or another, just as the mechanical philosophy did approximately two centuries ago.” Gayon has hedged his bets and made enough varying pronouncements to be right about at least one of them.

Tentative, Speculative

Nevertheless, the tentative and speculative nature of Gayon’s article is revealing. It at times almost amounts to hand-wringing. Whatever else may be said of this essay, it most assuredly would not have been part of the jubilant victory laps being run in Chicago fifty years before. Ann Reid, Eugenie Scott, Richard Dawkins, and a host of other Darwinian cheer leaders not mentioned here, seem to be lost in that generation that knew no limits for a neo-Darwinian paradigm at its height. But those days are gone.

Too much ink has been expended on questioning that paradigm from scientific and philosophical standpoints, the explication of which would require an annotated bibliography far beyond the limits of Evolution News. If the race is over for Darwinism, it now has settled into a vacant lumber, arms outstretched to any who will listen (and there’s still quite a few who will). In some ways the bloviating of Reid, Scott, and Dawkins sound like the cries of the living dead. Jonathan Wells is right — Zombie Science is real!

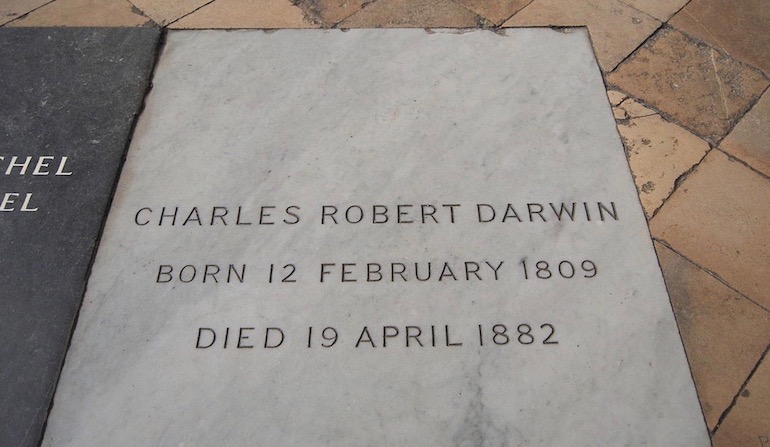

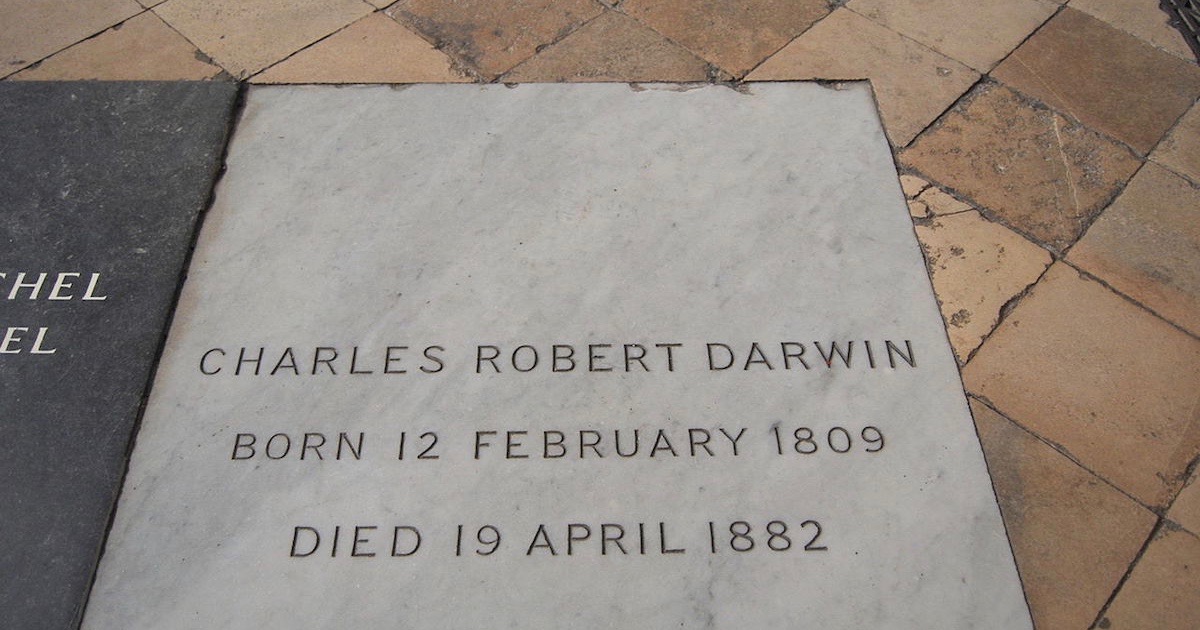

Photo: Tomb of Charles Darwin, Westminster Abbey, via Wikimedia Commons.