Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Medicine

Medicine

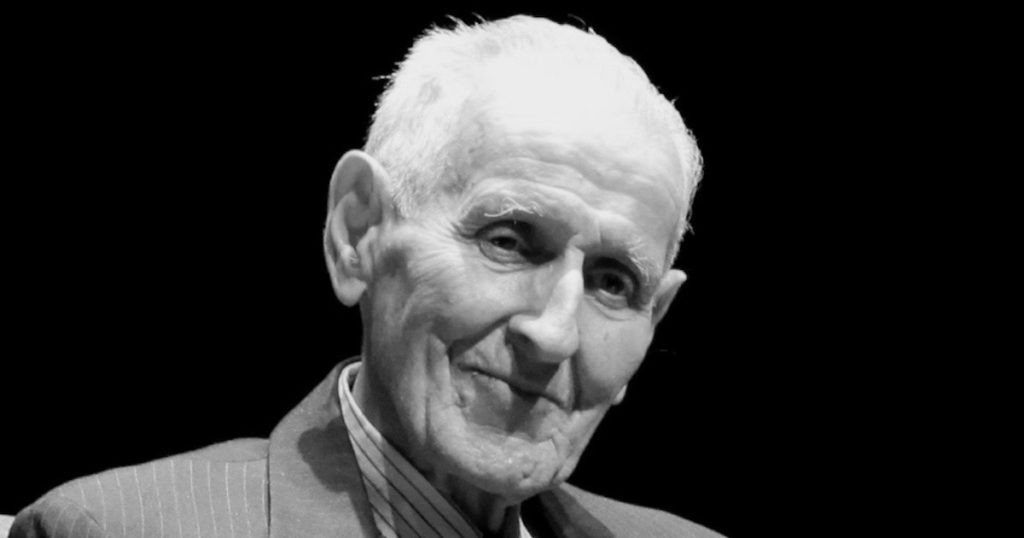

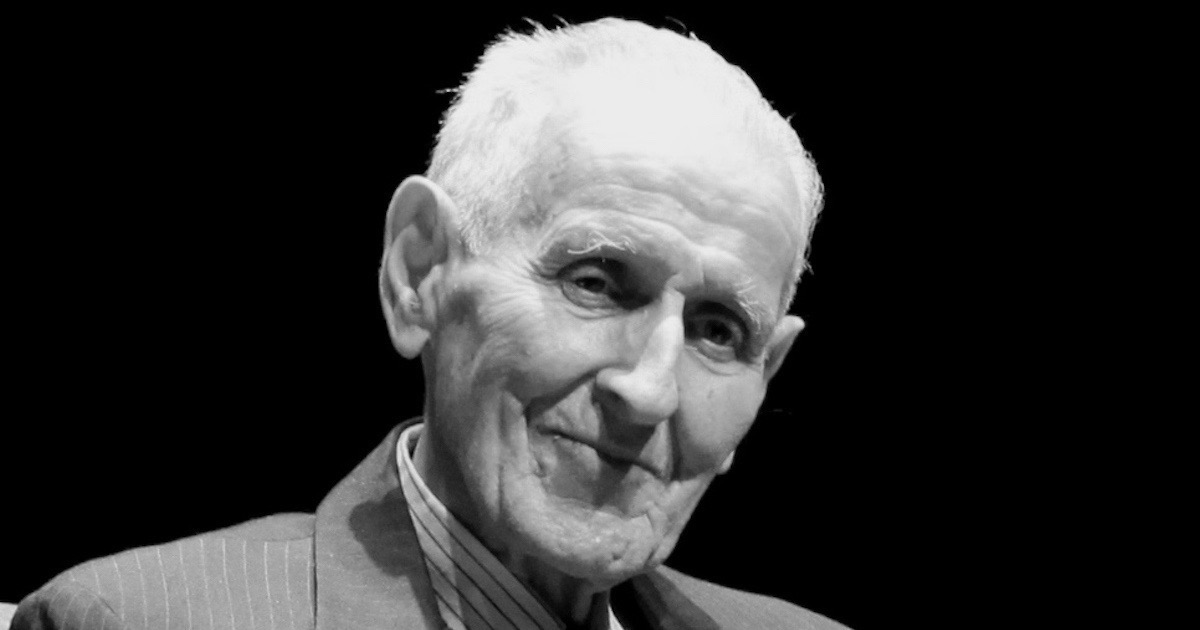

The Jack Kevorkian Plague

Death is in the air. No, I am not referring to the coronavirus. The pathogen I mean is a cultural pandemic, the embrace of doctor-prescribed suicide and of administered homicide as acceptable responses to human suffering.

Let’s call it the “Jack Kevorkian Plague,” after the late pathologist who in the 1990s became world-famous by assisting the suicides of some 130 people. Before Kevorkian, the euthanasia movement was mostly a fringe phenomenon. After Kevorkian, although certainly not because of him alone, assisted suicide had been made legal in Oregon, and large swaths of the American public accepted the practice.

Now, a mere 20 years later, lethal-injection euthanasia is legal and popular in Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Doctor-assisted suicide is legal in Germany, Switzerland, the Australian states of Victoria and Western Australia, and nine U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Pressure to legalize euthanasia is increasing in Australia, France, India, Italy, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

The media report stories about euthanasia and assisted suicide generally through the limited prism of “compassion.” Kevorkian attempted to justify his campaign likewise. But compassion was never his true motive. As he wrote in his book Prescription Medicide: The Goodness of a Planned Death, “Helping suffering or doomed persons kill themselves” was “merely the first step, an early distasteful obligation…that nobody in his right mind would savor.”

Not About Compassion

So, if it wasn’t about compassion, what was the real point? Kevorkian saw euthanasia as the perfect means to steer culture in a sharply utilitarian direction. Indeed, his great insight was that once society embraced that “distasteful first step,” the sanctity-of-life ethic — which he disdained, seeing it as an irrational religious belief — would be obliterated, and the door would be opened to using the bodies of people who commit suicide as natural resources available for utilitarian purposes.

Kevorkian gave several examples of what he meant. He thought that euthanasia clinics should be established that “make the quantum leap of supplementing merciful killing with the enormously positive benefit of experimentation and organ donation.” After all, he argued, if we are going to help people die, we might as well derive benefit from their deaths.

In 1998 he assisted the suicide of Joseph Tushkowski, a former police officer with quadriplegia. After Tushkowski died, Kevorkian ripped out the man’s kidneys — the medical examiner called it “a bizarre mutilation” — and then at a press conference offered them to the public, “first come, first served.”

Three Countries

Today, three countries —Belgium, Canada, and the Netherlands — have legally effectuated Kevorkian’s idea to join euthanasia to organ harvesting, although they don’t do it in such a crude fashion. Rather, suicidal persons go to the hospital to be killed, and immediately afterward their bodies are moved to a surgical suite for organ procurement. Canada has gone so far down the road that organ-donation organizations are advised in advance so that suicidal persons can be solicited for their organs.

Kevorkian also advocated child euthanasia. In 1988, in an article in Medicine and Law, he argued that babies born with disabilities “such as severe spina bifida, paraplegia, and hydrocephalus” should be candidates for euthanasia (and experimentation), provided that proper consent were given. Today, under a bureaucratic euthanasia checklist known as the Groningen Protocol, the Netherlands permits, although it has not explicitly legalized, infanticide for conditions of the kind that Kevorkian referenced. Netherlands law permits euthanasia more broadly for children twelve years of age and older.

In Belgium, there is no lower age limit for euthanasia. According to official euthanasia reports, in the past few years at least three children in Belgium have been euthanized, including a nine-year-old. Children in Canada cannot be euthanized, but that restriction may soon be repealed. Some pediatricians there have volunteered to euthanize minors once it becomes legal, perhaps even without parental consent, if the children are “mature.”

A Fundamental Right

Kevorkian believed that access to assisted suicide and euthanasia is a fundamental human right that should be available to any competent person wanting to die. Canada’s Supreme Court has partially agreed. In 2015 it established a right to “medical assistance in dying (MAiD),” as it is euphemistically called, for all competent patients with a medically diagnosed condition that causes “irremediable suffering,” including “psychological pain.” An Ontario court has ruled that this right to be killed is fundamental and that it trumps Canada’s Charter right of “freedom of religion and conscience.” Under the province’s rules of medical ethics, physicians who by religion or conscience are opposed to lethally injecting a sick patient must do so anyway or refer the patient to a doctor they know is willing to kill. If they don’t want to be complicit in such deaths, the court sniffed, they should get out of medicine.

Canada’s broad euthanasia license still requires an underlying medical diagnosis. Kevorkian opposed any such restriction. In Prescription Medicide he wrote that “optional assisted suicide” should be “available for individuals, sometimes in good physical and mental health who choose to be killed,” for whatever reason, including “physical (the end stage of incurable disease, crippling deformity, or severe trauma), mental (intense anxiety or psychic torture inflicted by self or others), or doxastic (religious or philosophical tenets or inflexible personal convictions).”

In Germany, Death as a Right

The Federal Constitutional Court in Germany recently ruled that such death on demand is a right. From the decision:

The right to a self-determined death is not limited to situations defined by external causes like serious or incurable illnesses, nor does it apply only in certain stages of life or illness. Rather, this right is guaranteed in all stages of a person’s existence. . . . The individual’s decision to end their own life, based on how they personally define quality of life and a meaningful existence, eludes any evaluation on the basis of general values, religious dogmas, societal norms for dealing with life and death, or consideration of objective rationality.

Kevorkian, too, thought that individuals should have a right to assisted suicide and that the decision should not belong only to medical professionals who would assist in the act. True to his vision, the German court has ruled that not only do citizens have a fundamental right to commit suicide or to be assisted in their suicide but that others have a concomitant right to assist.

Kevorkian advocated the establishment of regional euthanasia centers where people could go to be killed. Switzerland allows the operation of suicide clinics that people from around the world attend — that, indeed, they pay to attend. The Netherlands permits a “mobile” euthanasia service that makes house calls when a suicidal person’s own doctor refuses to participate in euthanasia.

No Impediment to Suicide

Kevorkian thought that mental illness should be no impediment to assisted suicide. In practice, that boundary has been crossed repeatedly, with the hastening of death made legal. For example, as reported in The American Journal of Psychiatry, Michael Freeland, an Oregonian, obtained a lethal prescription after being diagnosed with cancer. Subsequently he became psychotic and was committed to a hospital for depression with suicidal and possibly homicidal thoughts.

He was hospitalized for a week. The discharging psychiatrist noted with approval that, while Freeland’s guns had been removed from his house, the lethal prescription remained “safely at home.” In a further slap at true compassion, Freeland was permitted to keep the prescribed overdose even though the psychiatrist reported that he would “remain vulnerable to periods of delirium.” (Freeland died of natural causes more than two years after receiving the initial prescription.)

Meanwhile, in Belgium, a transsexual was euthanized legally after becoming distraught by a botched sex-change surgery. In another case there, a psychiatric patient, taken advantage of sexually by her psychiatrist, was euthanized by his replacement because she was so distressed over the victimization. Elderly couples who don’t want to be widowed have received joint euthanasia killings. The list of the mentally ill and distraught people who are not otherwise sick but who have died by euthanasia or assisted suicide goes on and on, not just in Belgium but across the Western world.

What Is “Obitiatry,” You Ask?

About the only policy that Kevorkian advocated that has not yet been implemented somewhere in the world is what he called “obitiatry.” What is that, you ask? it is human vivisection on living patients before euthanasia. He wrote in Prescription Medicide:

If we are ever to penetrate the mystery of death — even superficially — it will have to be through obitiatry. Research using cultured cells and tissues and live animals may yield objective biological data, and eventually perhaps even some clues about the essence of mere vitality or existence. But knowledge about the essence of human death will of necessity require insight into the nature of the unique awareness or consciousness that characterizes cognitive human life. That is only possible through obitiatric research on living human bodies, and most likely concentrating on the central nervous system.

Will we ever conduct experiments on patients before they are euthanized? I hope not. But the question must be asked: How can it be forbidden logically, once we embrace Kevorkian values?

A More Rational Future

In his day, Kevorkian believed that human life was expendable. Increasingly, so do we. He advocated a radical definition of personal autonomy, countenancing suicide as a right. Increasingly, we do too. He promoted a naked utilitarianism according to which human body parts could be deemed more important than the principle that the life of a suicidal person should be preserved. His view on this matter now prevails in three major Western countries: Belgium, Canada, and the Netherlands. In that light, why not allow lethal experiments on people who want to die and to benefit society in the process, by becoming research subjects?

Let me conclude this depressing essay with a few simple questions. Did it shock you? Were you outraged by the extent to which Kevorkian’s twisted vision is being implemented? Did it at least make you queasy? If not, that fact alone demonstrates how thoroughly the Jack Kevorkian Plague permeates our culture.

Kevorkian was convinced that he was leading society into what he considered a more rational future, one in which the value of life would be relative and the bodies of the suicidal commodified. At the time, most observers rolled their eyes and assured us that it could never happen. But it has happened and is happening.

Photo: Jack Kevorkian, speaking at UCLA, by RaffiJackMayer.JPG: Halebtsiderivative work: Francesco 13 / Public domain.

Cross-posted at National Review.