Free Speech

Free Speech

What Triggered a Biology Journal to Demand Government Censorship of Intelligent Design

As noted here already, the prominent science journal BioEssays has issued a remarkable editorial by biologist Dave Speijer, “Bad Faith Reasoning, Predictable Chaos, and the Truth.” The article is like a thermometer measuring a fever among evolutionists. Speijer calls for intelligent design websites, including the one you’re reading now, to be censored by government mandate. And he’s quite serious. It would be shocking were it not for the fact that censors are already empowered at YouTube, Facebook, and on other social media, to scour the Internet and wipe out ideas they don’t like. This is not a drill.

The editorial proposes that search engines be required to “have mandatory color coded banners warning of consistent factual errors or unscientific content, masquerading as science.” BioEssays sounds off against proponents of intelligent design, saying we use “bad faith reasoning,” “misquote” in order to “subvert belief in Darwinian evolution,” promote “non‐scientific explanations,” and engage in “spreading misinformation.” A crude graphic accompanies the article, calling ID proponents “Bio-Liars.”

Not content with just a little hysterical overwriting, Speijer goes on to call us the “infamous Discovery Institute” that promotes “creationism in a tuxedo.” That’s not a cheap tuxedo, mind you, as the insult usually goes. We are moving on up, in our wardrobe as in the peril that diehard Darwin defenders believe that we pose. In Speijer’s telling, we are guilty of “peddling unscientific, untenable positions, using ‘cut and paste’ distortions.” We publish “consistent factual errors or unscientific content, masquerading as science.” Some of these bad arguments include the claim that “life is so complicated that it cannot be the result of random processes,” a position that he says can be refuted by citing “many examples of unintelligent or even downright stupid designs found in living organisms.” With unintended irony, he goes on to lament the “deterioration of our media ecosystem” where debates should only take place among those who are part of a “mature complex society.”

What exactly were the falsehoods on ID “Bio-Liar” websites that led the mature and complex editors of BioEssays to publish this tirade? It was two articles Dr. Speijer read on Evolution News that set him off. A lot is at stake (free speech, for one thing) so let’s take a look in some detail.

Junk DNA and Andrew Moore

One of the offending articles was published here last November, “BioEssays Editor: “‘Junk’ DNA… Full of Information!” Including Genome-Sized “Genomic Code.” Speijer says:

A big problem with grasping the nature of complexity, unpredictability, and layers of interactions is a recurring theme in the “anti‐evolution” community. Not so long ago, Andrew Moore speculated about the extent to which the so‐called junk DNA might be performing (non‐coding) functions, taking his inspiration from a BioEssays paper by Giorgio Bernardi, claiming that (much of) it might be involved in orchestrating the nuclear chromosomal architecture. I presume he was somewhat surprised when he encountered quotes taken from his column under the heading of “intelligent design,” considering he so clearly dealt with the issues at hand from an evolutionary perspective. However, on reflection, this happening could have been predicted with high likelihood.

Here is his complaint: ID proponents fail to grasp “the nature of complexity, unpredictability, and layers of interactions” in genomic studies. Speijer thinks the staff-authored article at Evolution News misrepresented BioEssays editor Andrew Moore, making it appear he advocates intelligent design, whereas Moore “so clearly dealt with the issues at hand from an evolutionary perspective.”

So did our article misrepresent Andrew Moore? Not in any way, shape, or form. In fact, it explicitly stated that he is not an ID supporter, and is an evolutionist:

Moore is not an ID proponent; he’s clearly writing from an evolutionary perspective. Even as he describes extensive function in our genome, he frequently adds evolutionary “narrative gloss” just to remind you what side he’s on.

The article continues:

Though clearly evolution-based, Moore’s perspective stands out in an important way: it is open to seeing coordinated function across the entire genome.

And again:

Moore’s evolutionary bias is evident here as he repeatedly adds “narrative gloss,” ascribing functional aspects of our genome to evolution, rather than simply describing the functional nature of DNA and leaving evolution out of it. But the substance of what he’s saying identifies function in an aspect of the genome that evolutionists have frequently ignored as junk.

Finally:

So here’s what we have: evolutionary scientists proposing that most of our genome’s sequence has functional importance because it carries a genomic code, controlling the three-dimensional packing in the nucleus.

The article repeatedly clarified that Andrew Moore is not an ID proponent. We added our own commentary about how the scientific evidence discussed by Moore is better explained by an intelligent design perspective (which has long predicted extensive function for noncoding DNA) than by an evolutionary perspective (which has repeatedly predicted that non-coding DNA was junk).

If Speijer were interested in accurately representing our article, he should at least have recognized that it in no way portrayed Moore as being supportive of ID. Instead, in the same paragraph, here’s how Speijer describes our views:

In the famous words of Jacques Monod, biological phenomena can be explained by the interaction of chance and necessity (random occurrences and natural laws). In the eyes of anti‐evolutionists there is no role for chance, and thus they zoomed in on the aspect that (some) junk DNA actually might have important functions. Sad to say, the source of much of the junk DNA is still to be found in chance (think of pseudogenes, repeat sequences, transposons, and viral elements). The second temptation for adherents of intelligent design lies in the fact that the phenomena described can be seen as imposing multilevel constraints (for instance, a sequence has to correctly encode a protein and allow proper chromosomal organization). Logically, the chances of getting sequences that work on both levels seem slimmer. Thus, they would feel empowered to bring back their old chestnut: “life is so complicated that it cannot be the result of random processes.”

Set to one side Speijer’s dubious claims that non-coding genetic elements like pseudogenes, repeats, or transposons should be assumed to be useless genetic junk. In January we reported on a new article in Nature Reviews Genetics arguing that pseudogene function is “prematurely dismissed” based upon “dogma,” because “Where pseudogenes have been studied directly they are often found to have quantifiable biological roles.” The very article we reviewed by Andrew Moore recognizes that vast stretches of the genome — composed largely of repeat sequences and transposable elements and supposed viral sequences — seem to have genome-scale functional roles. Those issues aside, there are many misrepresentations in Spiejer’s passage about how ID reasoning operates.

Give Chance a Chance

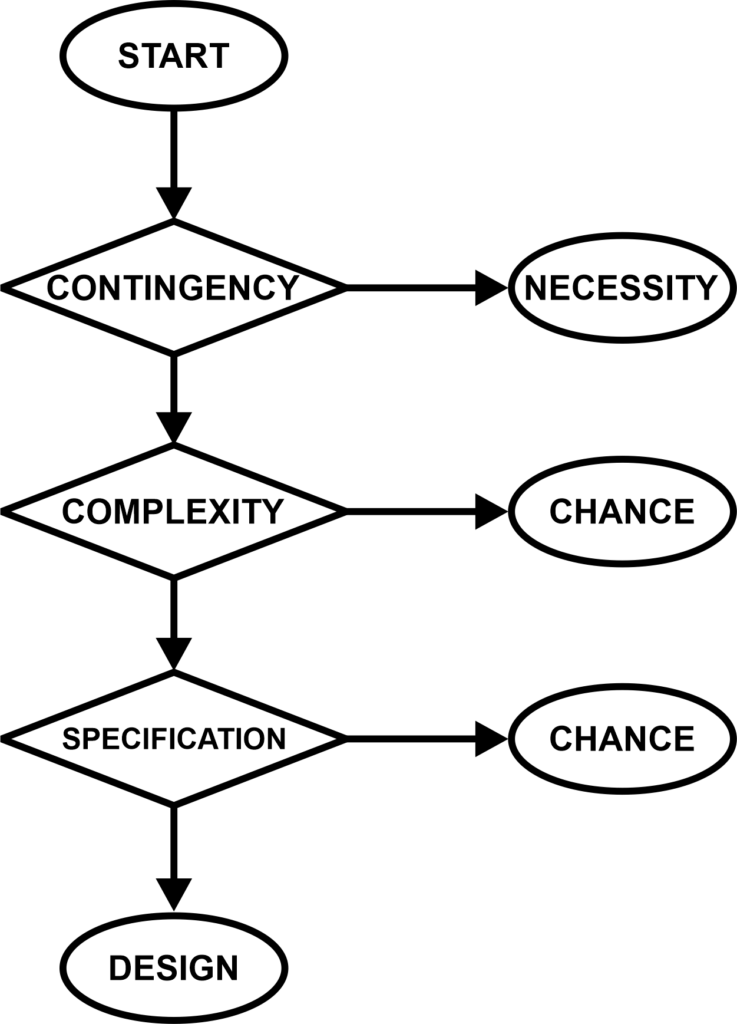

Is it true that for ID proponents “there is no role for chance,” as Speijer claims? Anyone who has read foundational ID books like William Dembski’s The Design Inference, or even any of Dembski’s popular treatments, will know that ID proponents fully recognize that chance, law, and chance + law are all forces at work in nature. Dembski’s explanatory filter has appeared in numerous ID publications and is one of the key logical methods of detecting design. Here’s a diagram showing how the filter works:

As seen in the diagram, in this method, “chance” is a perfectly valid explanation for natural events. Only when neither chance nor necessity can explain a feature, where the feature contains high levels of “complexity” and shows “specification,” then do we draw the inference that it was designed.

Stephen Meyer’s book Signature in the Cell clearly recognizes the potential role of chance in the origin of life:

[O]ne of Francis Crick’s colleagues was the French biologist Jacques Monod. In 1971 he wrote an influential book called Chance and Necessity, extolling the powers of chance variation and lawlike processes of necessity in the history of life. As an example of a chance process, Monod noted how random mutations in the genetic makeup of organisms can explain how variations in populations arise during the process of biological evolution. In Monod’s shorthand, “chance” referred to events or processes that produce a range of possible outcomes, each with some probability of occurring. The term “necessity,” on the other hand, referred to processes or forces that produce a specific outcome with perfect regularity, so that the outcome is “necessary” or inevitable once some prior conditions have been established.

Signature in the Cell, pp. 173-174

Passages like that can be found in many ID works. They show that ID proponents like Meyer are well aware of Monod’s ideas. Do Meyer deny the role of chance? No.

Dembski notes that, as we reason about these different kinds of events, we often engage in a comparative evaluation process that he represents with a schematic he calls the “explanatory filter.” The filter outlines a method by which scientists (and others) decide among three different types of attributions or explanations-chance, necessity, and intelligent design-based upon the probabilistic features or “signatures” of various kinds of events. (See Fig. 16.1.) … In Chapter 8, I described how Dembski came to recognize that low-probability events by themselves do not necessarily indicate that something other than chance is at work. Improbable events happen all the time and don’t necessarily indicate anything other than chance in play-as Dembski had illustrated to me by pointing out that if I flipped a coin one hundred times I would necessarily participate in an extremely improbable event. In that case, any specific sequence that turned up would have a probability of 1 chance in 2100. Yet the improbability of this event did not mean that something other than chance was responsible.

Signature in the Cell, pp. 354-355

Recapitulating an Old Chestnut

Let’s turn to Speijer’s claim that ID reasons that “life is so complicated that it cannot be the result of random processes.” Speijer calls this argument an “old chestnut” and indeed that’s what it is: a hoary misrepresentation of ID arguments. We have addressed it numerous times (for example, see here, here, here, here, or here).

First, ID does not merely refute “random processes.” As Dembski’s explanatory filter and the passage from Meyer’s book show, ID theory evaluates the ability of chance, law, and a combination of chance + law to explain elements of nature.

Second, ID does not begin by naïvely arguing that “life is so complicated…” ID is inferred only after careful quantitative analyses show that random mutation and natural selection cannot produce a given feature. This is not a simple or naïve argument. ID proponents have implemented complex population genetics models (which appropriately incorporate the roles of chance mutation and nonrandom selection) to test the efficacy of Darwinian evolutionary mechanisms. For some examples from the ID research literature, see here, here, or here.

Third, ID is not just a negative argument against material causes. Simply finding that Darwinian mechanisms are unable to produce a feature is not enough to infer design. Intelligent design is inferred only from a positive argument where we find the type of information and complexity in life that is known to derive from an intelligent agent. This type of information is called specified complexity, as Stephen Meyer explains:

[T]he inadequacy of proposed materialistic causes forms only part of the basis of the argument for intelligent design. We also know from broad and repeated experience that intelligent agents can and do produce information-rich systems: we have positive experience-based knowledge of a cause that is sufficient to generate new specified information, namely, intelligence. We are not ignorant of how information arises. We know from experience that conscious intelligent agents can create informational sequences and systems. To quote Quastler again, “The creation of new information is habitually associated with conscious activity.” Experience teaches that whenever large amounts of specified complexity or information are present in an artifact or entity whose causal story is known, invariably creative intelligence-intelligent design-played a role in the origin of that entity. Thus, when we encounter such information in the large biological molecules needed for life, we may infer-based on our knowledge of established cause-and-effect relationships-that an intelligent cause operated in the past to produce the specified information necessary to the origin of life.

For this reason, the design inference defended here does not constitute an argument from ignorance. Instead, it constitutes an “inference to the best explanation” based upon our best available knowledge.

(Signature in the Cell, pp. 376-377)

Poorly Designed Objections

This brings us to Speijer’s fourth mistake: the error in thinking that ID arguments are turned back by examples of supposed poor design. This is another classic:

Here is a concept that was invoked as an “explanation” after many examples of unintelligent or even downright stupid designs found in living organisms started littering biology books. One might understand why I think it a bit rich that they advocate reasoned explanations under headers such as “truth in science,” whilst peddling unscientific, untenable positions, using “cut and paste” distortions.

And exactly what are the “unintelligent or downright stupid designs” that show life was not designed? Speijer doesn’t say. We’ve tackled many such arguments over the years, responding to assertions about the “poor design” of the vertebrate eye, panda’s thumb, whale pelvic bones, appendix, coccyx, sinuses, or laryngeal nerve, among others. Brian Miller has explained the general problem with the “imperfection-of-the-gaps fallacy,” which unscientifically presumes we have near-perfect knowledge of how organisms ought to operate. Another problem with such arguments is that poor design is still design, as we have previously explained:

As a science, ID doesn’t address theological questions about whether the design is “desirable,” “undesirable,” “perfect,” or “imperfect.” Undesirable design is still design. Gilmour just doesn’t like it because (in his own subjective view) it’s undesirable. Here’s a quick illustration of what I mean:

I’m writing this on a PC using Windows; this PC has crashed probably a dozen times in the past two weeks. Right now, I hate my PC. I consider it poorly designed, full of imperfections, and very undesirable. Does that mean it wasn’t designed by intelligent agents? No. “Undesirable design” and “intelligent design” are two different things. “Undesirable,” “poor,” or “imperfect” design do not refute intelligent design.

Speijer is critiquing a straw man.

What about the nefarious misdeeds that Speijer accuses Evolution News of committing — using “misquote[s]” and “’cut and paste’ distortions” in pursuit of “spreading misinformation,” to name a few? It’s because of such wrongdoing that he suggests we need to be censored by the government. But consider: Did Speijer accurately represent our article on junk DNA, or did he falsely imply it presented Andrew Moore as a proponent of ID? Did Speijer use cut-and-paste common distortions about ID by saying it argues “life is so complicated that it cannot be the result of random processes”? Did Speijer spread misinformation or use “bad faith reasoning” about ID by claiming that it is refuted by “unintelligent or downright stupid designs”? Oh, and is it consistent for the editorial to call us “Bio-Liars” who promote “creationism in a tuxedo” while lamenting the “deterioration” of public discourse with its dearth of “mature” participants? Are Speijer’s criticisms more applicable to ID proponents, or to his own attacks on us?

Misuse of Popper?

Speijer has another complaint. It’s about a brief article by Paul Nelson here, back in February. Nelson was responding to a short editorial, “Is Popperian Falsification Useful in Biology?,” that Speijer had written in BioEssays. Here is the offending passage from Nelson:

An open access editorial (whose title I have borrowed for the headline), by the Dutch biologist Dave Speijer, is worth a look in relation to this issue.

“[E]volutionary theory,” he writes, “invites us to tolerate exceptions.” I think this is exactly wrong. A theory that predicted the exceptions to its rules and generalizations would convey knowledge. A theory that “tolerates exceptions,” however, will end up in a 1:1 mapping with whatever one observes — in which event, the theory is doing no work at all, simply wandering along behind the data like a puppy on a leash.

That’s the entirety of what Nelson said about Speijer. Was this a misquote? Consider what Speijer originally wrote:

Of course, overall Popper is right. Trying to establish facts that disprove broad theories is a worthwhile strategy, often generating further insights. However, the example above illustrates the problems involved: these only get worse when one turns to the field of biological theory. The complexity of biological entities (highly complicated systems that have many layers of intra‐ and interconnectivity, themselves results of eons of prior development) is such that “counter‐examples” are sometimes not what they seem to be. Allow me to give some examples. Eukaryotes are capable of a complicated system of procreation: full meiotic sex. However, less costly clonal (non‐sexual) propagation also occurs. Most instances turn out to be relatively short‐lived, but an exception to this “rule” is found in the bdelloid rotifers, which lost meiotic sex millions of years ago. Does this mean that sex is just something that eukaryotes got stuck with, and that it is lost again as soon as the opportunity arises? Of course not. The exception might inform the rule. Because they live in cyclically drying freshwater habitats, bdelloid rotifers evolved high resistance to reactive oxygen species (ROS) resistance (in their case coming from ionizing radiation more than from the mitochondrion). This might have made the DNA repair mechanisms associated with meiotic sex superfluous.2 What of other exceptions to biological rules? The mitochondrial DNA is practically always inherited from the maternal germ cell. Is that indeed because the “active” (motile) germ cell (sperm) has more ROS‐related damage, or do a few exceptions disprove this? Highly complex eukaryotic structures are almost always associated with an aerobic lifestyle. Does an instance of anaerobic complexity tell us that this is just a coincidence? In both cases I do not think so. Or take the mitochondrial ROS theory of aging: does the observation that an active lifestyle is conductive to longevity invalidate it? Careful analysis shows this not to be the case. In biology, “largely true” correlations often give important insights. Thus, at the risk of constructing our own Vulcans to prop up flawed models, evolutionary complexity invites us to tolerate exceptions.

Everyone seems to agree (to some extent) that the predictions of evolutionary biology often meet with counterexamples. Speijer dismisses this as unimportant, simply reflecting the “eons of prior development” that led to great “complexity of biological entities” with “highly complicated systems that have many layers of intra‐ and interconnectivity.” Paul Nelson thinks that these failed predictions ought not to be dismissed, unless you are willing to tolerate a theory that fails to generate useful knowledge.

Nelson made a fair point, if you ask us, but feel free think otherwise. Are the editors of BioEssays so afraid of criticism that even very benign disagreement triggers them to call for government-backed censorship?

To be fair, Nelson’s original post included a slight misquote of Speijer. It was unintentional, of course, and didn’t change the meaning. Speijer spoke of “evolutionary complexity” rather than “evolutionary theory,” as Nelson first wrote. Naturally, we’ve since fixed that. Speijer doesn’t mention it, so apparently it wasn’t a big deal to him. What is a big deal to Speijer is that Nelson quotes Stephen Jay Gould. Speijer responds:

My concluding remark, regarding biology inviting us to tolerate exceptions, is quoted (without the crucial proviso, however) to just mean “anything is possible.” Talk about “bad faith” reasoning. But at least I was trashed together with the late Stephen Jay Gould, so that softened the blow to my ego.

But did Paul Nelson say that Speijer said that under evolutionary biology “anything is possible”? No, he did not. Rather, he quoted a different scientist commenting on Stephen Jay Gould. Nelson wrote:

Stephen Jay Gould grew very fond of the notion of “contingency,” which he would deploy to rationalize departures from prediction. If that seems a harsh judgment, consider the last sentence of this article, commenting on Gould’s position:

“Organisms tend to achieve similar solutions to similar problems, but give it [i.e., evolution] enough time (or a small enough population), and anything is possible.”

“Anything is possible” may be true — but then, don’t pretend you have a theory which is doing any real work. You don’t.

When Nelson cites “this article” he doesn’t link to Speijer. He links to an article by Tiago Rodrigues Simões, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard. Speijer is upset that Nelson quoted another scientist talking about the views of Stephen Jay Gould in an article that also separately critiqued Speijer’s own views. That’s what all the furor is about. That’s why he was triggered into calling for censorship.

Well, actually there’s one other thing that Speijer is angry about — and it reduces to the mere fact that Nelson advocates intelligent design:

The Discovery Institute (and its websites) has a tendency of adding insult to injury. To quote from a column which mentions Popper’s falsifiability criterion as a way of distinguishing scientific and non‐scientific explanations to advance intelligent design is audacious to say the least.

Again, Nelson simply suggested that Popper’s thinking should be applied to evolutionary theory. His post doesn’t say anything about ID. But of course Nelson is an ID advocate. For Speijer, it seems, the mere fact that Nelson advocates ID means he is guilty of “peddling unscientific, untenable positions, using ‘cut and paste’ distortions.” Audacious to some, indeed.

The Lady Doth…

What has Speijer identified in our work that amounts to real misquotes, errors, or bad logic? Nothing. Nelson too was also unable to find anything that he had done wrong. Soon after Speijer’s editorial was published by BioEssays, Nelson wrote a friendly email to Speijer. Nelson essentially asked, Did I get anything wrong? Let’s talk, because if I did I want to correct the record and make it right.

That email was sent well over a month ago. The response to Dr. Nelson from Dr. Speijer? Crickets.

So there you have it. These scientists were triggered by nothing. They erupted in response with demands for persecution. Does this sound to you like a sober, mature, balanced scientific outlook, one that should be dictating government policy on Internet freedom? These are the upholders of orthodox evolutionary theory! These are Darwin’s modern champions. Paul Nelson said it well in his post: evolutionary biology “is not a healthy theory.”

Photo credit: christian buehner via Unsplash.