Evolution

Evolution

Human Origins

Human Origins

As Science Frauds Go, Haeckel Beats Piltdown Man

Ecologist Jeremy Fox at the University of Calgary offers a list of scientific frauds, with Piltdown Man at the top of the list. Writing at his blog Dynamic Ecology, he remarks, “Gonna be hard to top this one, I think.” Is it? From, “What’s the ‘greatest’ scientific fraud of all time?”

Charles Dawson (it almost certainly was him) faked actual fossils rather than, say, numbers in a spreadsheet. Although he didn’t fool everyone, he fooled enough people (including some of the leading paleontologists of the day) to appreciably influence research on human evolution. The fraud wasn’t definitively exposed until more than 40 years had passed. By way of comparison, think of the fake “Archaeoraptor” fossil from a few years ago — it only fooled a fossil collector and a few people associated with National Geographic, and was exposed within weeks.

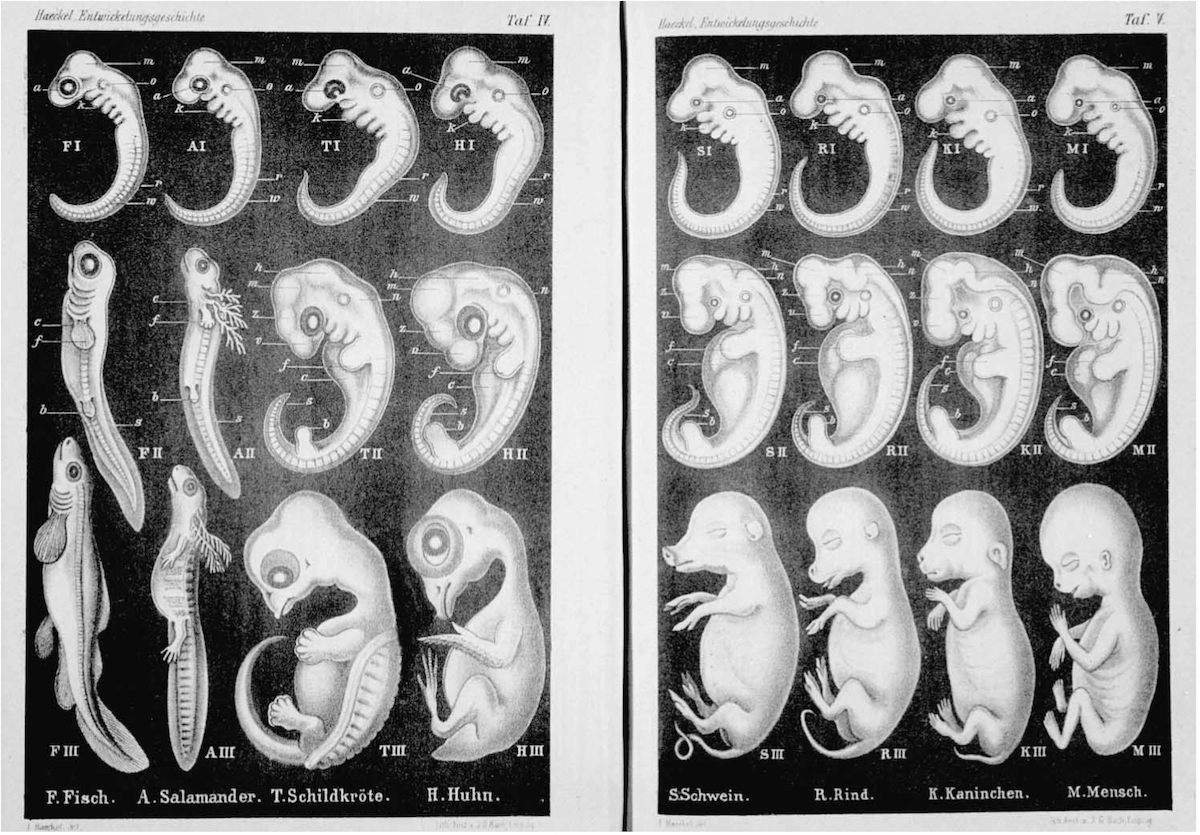

I can top that. Sure, 40 years is a long time but it is a lot less than 140 years or so. Ernst Haeckel’s famous and fraudulent embryo illustrations have been in circulation a good century longer than Piltdown was, last time we checked. Despite being exposed prominently by Jonathan Wells in Icons of Evolution (2000), they continued to be featured in biology textbooks as recently as 2016. Evolution News compiled an extensive list of textbooks in 2015 and Dr. Wells reported again in Zombie Science (2017). For reference, the illustration below is from 1874.

What’s striking, as we have said, is that variations on the Haeckel drawings were not being used just to provide historical background but as representing scientific evidence, suitable for students learning about the theory of evolution. Our list — see “Haeckel’s Fraudulent Embryo Drawings Are Still Present in Biology Textbooks” — included textbooks that:

(1) Show embryo drawings that are either Haeckel’s originals or highly similar or near-identical versions of Haeckel’s illustrations — drawings that downplay and misrepresent the differences among early stages of vertebrate embryos;

(2) Have used these drawings as evidence for current evolutionary theory and not simply to provide some kind of historical context for evolutionary thinking;

(3) Have used their Haeckel-based drawings to overstate the actual similarities between early embryos, which is the key misrepresentation made by Haeckel, even if the textbooks do not completely endorse Haeckel’s false “recapitulation” theory. They then cite these overstated similarities as still-valid evidence for common ancestry.

Piltdown Man may have “appreciably influence[d] research on human evolution” but Haeckel’s illustrations have influenced countless students who assumed, innocently but falsely, that what they were looking at was genuine evidence for Darwinian evolution. Piltdown Man is a historical curiosity. Haeckel continues to resound in our minds today.