Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Darwinism as the Root Problem of Modernity

Editor’s note: The following, second in a three-part series, is adapted from an essay in National Review and is republished here with permission. Professor Aeschliman is the author of The Restoration of Man: C.S. Lewis and the Continuing Case Against Scientism (Discovery Institute Press). Find the full series here.

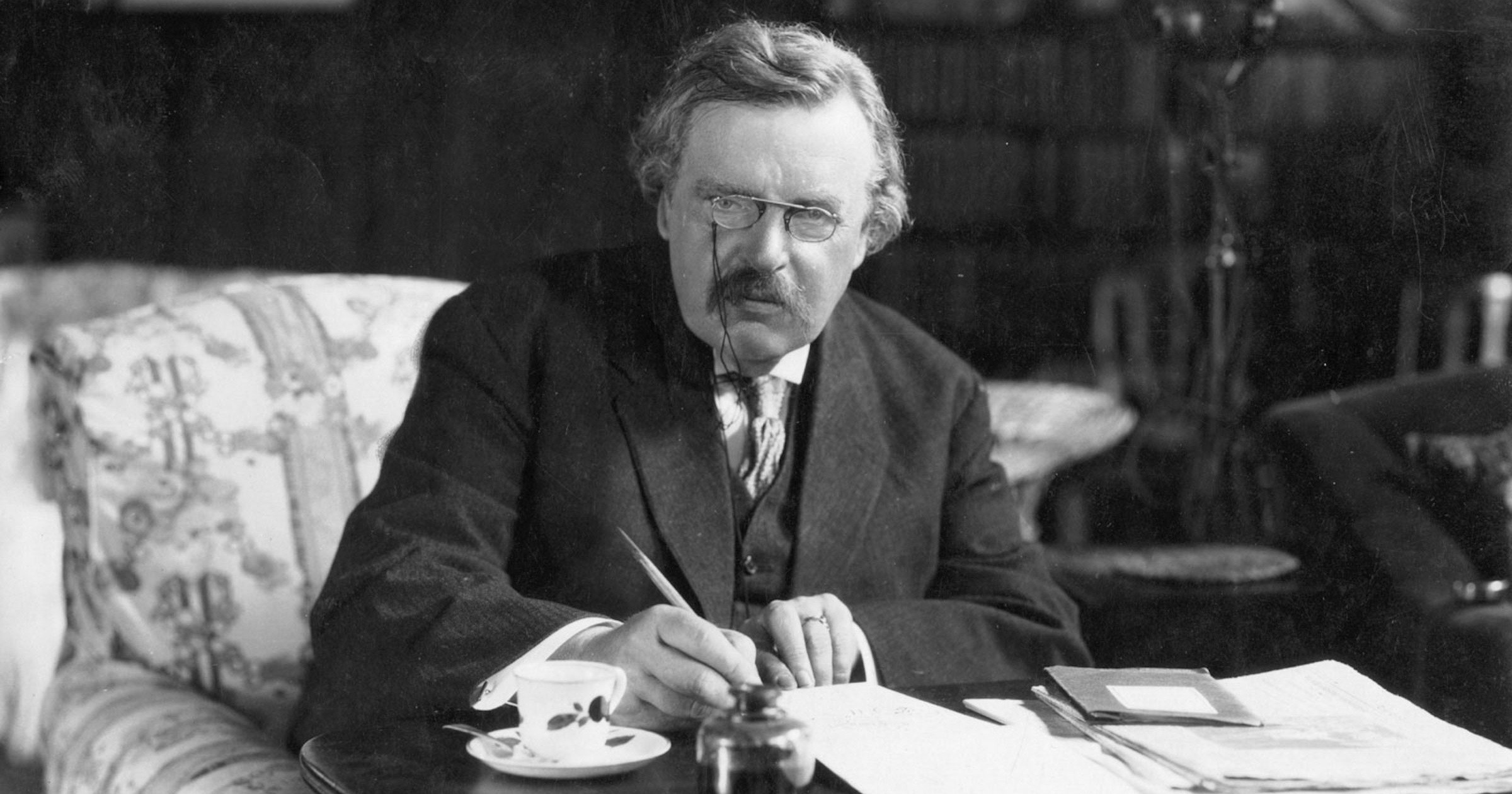

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), a witty Dublin Protestant-atheist Irishman like George Bernard Shaw, but of a very different class, stamp, and implication, wrote that natural science, “by revealing to us the absolute mechanism of all action, [frees] us from the self-imposed and trammeling burden of moral responsibility.” Wilde’s resultant, post-Christian aesthetic immoralism shocked and mocked the “earnestness” of late Victorian Britain in witty prose and plays, including the satirical wit (and homosexual implication) of The Importance of Being Earnest (1895). Both Shaw and G. K. Chesterton had an intimation that Wilde’s witty persiflage actually disguised deep decadence, an argument made brilliantly several decades later by the American Jewish moralists Philip Rieff (“The Impossible Culture: Wilde as a Modern Prophet,” 1982–83, reprinted in The Feeling Intellect, 1990) and Daniel Bell (The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism, 1976; “Beyond Modernism, Beyond Self,” 1977). From Wilde came the Bloomsbury aesthetes and, we may say, nearly the whole world of the modern arts.

Yet both Shaw and Chesterton were themselves noted wits (both sometimes even accused of being paradox-mongering buffoons), and in fact Shaw shared much of the iconoclasm of his countryman Wilde, becoming a self-described feminist, Nietzschean, Ibsenite, and Wagnerite. But for Chesterton one of Shaw’s great achievements was his deep, abiding hatred of aestheticism — Shaw even insisted that the Puritan evangelist John Bunyan (The Pilgrim’s Progress) was a greater writer than Shakespeare, and frequently, unaccountably, made orthodox statements, such as “There is a soul hidden in every dogma” and “Conscience is the most powerful of the instincts, and the love of God the most powerful of all passions.” Along with T. S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral (1935) and Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons (1960), Shaw’s play St. Joan (1924) is one of the wisest, wittiest, and most sympathetic dramatic depictions of Christian religious belief in the last hundred years.

Both Shaw and Chesterton believed that the root problem of modernity was Darwinism, the acceptance of which made it impossible to resist its moral corollary, social Darwinism, and therefore plutocracy, amoral capitalism, imperialism, racialism, and militarism. Shaw wrote in the preface to Man and Superman (1903): “If the wicked flourish and the fittest survive, Nature must be the god of rascals.”

“Three Blind Mice”

Though Shaw was a small-p protestant religious heretic (he argued that Joan of Arc was an early Protestant, like Hus and Wycliffe), Chesterton asserted that he was a true if eccentric Puritan moralist. Shaw’s critique of Darwinism was profound, especially in the long preface to his mammoth play Back to Methuselah (1921): The literary critic R. C. Churchill has called this preface “the wittiest summary of the Darwinian controversy ever written” (see especially the sections from “Three Blind Mice” onward). In his own 1944 postscript to the play, Shaw, while still insisting on the need to give up the Protestant creed (and all other Jewish and Christian creeds) of his youth in the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy in Dublin, held that Darwin’s exclusion of mind and purpose from nature was wrong and destructive: Unless we can reclaim mind, will, and purpose as realities in some kind of non-Darwinian, “creative evolution,” we “fall into the bottomless pit of an utterly discouraging pessimism.”

Shaw’s predecessor Samuel Butler (1835–1902), and his Franco-American successor and admirer Jacques Barzun (1907–2012), have made similar arguments, arguments given renewed strength more recently by the American philosopher Thomas Nagel (see my “Rationality vs. Darwinism,” National Review, 2012). Shaw’s resistance to determinism, and his insistence on the irreducible reality of human consciousness and will in nature and history, elicited Chesterton’s profound respect and admiration. In his final, 1935 chapter on Shaw, written in the last year of Chesterton’s own life, he said of the older man’s achievements in drama over the previous 40 years: “He has improved philosophic discussions by making them more popular. But he has also improved popular amusements by making them more philosophic.” He added that Shaw was “one of the most genial and generous men in the world.”

To Sleep and Never Wake

Yet Chesterton’s admiration and approval were shadowed by a sense that Shaw had great deficiencies and that his influence was ambiguous and in some cases malignant. Born 18 years earlier than Chesterton, Shaw outlived him by another 16, his life encompassing both world wars, unprecedented destruction, and the fundamental disproof of his early progressivism and cosmopolitanism. His early Fabian socialism led him to become an influential communist fellow traveler. The famously exuberant, energetic Shaw told his biographer Hesketh Pearson, a close friend of Malcolm Muggeridge, that, in the post–World War II world, he wished when he went to bed that he would never wake again.

Like H. G. Wells, he was threatened with “an utterly discouraging pessimism” when his political hopes came to seem almost completely vain. Commenting on the significance of Aldous Huxley’s satirical dystopia Brave New World (1932), even before George Orwell’s 1984, an English writer quoted by Chesterton in his 1935 chapter said, “Progress is dead; and Brave New World is its epitaph.” Beyond the world of fiction, in the world of actual human tragedy, works such as Elie Wiesel’s Night and Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago may be said to have proved the point unanswerably: Human progress may be possible, based on willed choices, but there is certainly no mystical, progressive, propulsive purpose immanent within history.

An Outsider in Three Ways

Chesterton’s argument about Shaw from the beginning was that he was in three ways an outsider, ways that gave him a unique perspective and insight but that also prevented his understanding what Chesterton thought of as a fundamental piety that had been characteristic of Western civilization and Western societies at their best: Shaw was a Protestant Anglo-Irishman who disdained his own country and left it permanently for London; he was emotionally, intellectually, and politically a fastidious Puritan moralist who could not, however, believe any longer in the Puritan God; and he was a Nietzschean-socialist futurist whose disgust with the human past and its traditions made him an ultimate outsider to any particular historical community or continuity.

Free from what Chesterton called the “vile” aesthetic philosophy of his also-cosmopolitan Irish countryman Wilde, “a philosophy of ease, of acceptance, and luxurious illusion,” Shaw read and was deeply affected by Nietzsche after having committed himself, in mind, action, and loyalty, to the Fabian-socialist cause, making lifelong friends and allies of Sidney and Beatrice Webb, whom he was instrumental in getting buried with full honors in Westminster Abbey in 1947. But reconciling Nietzsche with socialism was a lifelong conundrum, and it should be no surprise that Shaw came to admire “strong men” beyond the bourgeois-democratic tradition and temper — such as Mussolini, Stalin, and the British fascist Sir Oswald Mosley. “Stalin has delivered the goods,” the celebrity Shaw wrote in 1931, the year of his state-conducted tour of Russia with his friend Lady Astor. A photo of the two of them in a chauffeured car on Red Square in Moscow is on the cover of David Caute’s indispensable book The Fellow Travellers: A Postscript to the Enlightenment (1973), a brilliant documentation of the lamentable credulity of Western intellectuals in confronting Lenin, Stalin, and what the Webbs called the “new civilization” of the Soviet Union. Shaw died in his English country house in 1950 with a signed photograph of Stalin on his mantelpiece.

Chesterton’s brief study of 1909 and its even briefer 1935 sequel were thus profoundly apt in assessing Shaw’s greatness and his folly. He saw that Shaw was really no democrat, that his admirable public spirit had in it something cold, abstract, theoretical, and even Platonist in the sense of Plato as an elitist authoritarian; whereas Chesterton himself was truly a kind of democrat, actually liking “the common man” and assuming that human beings across time had come to certain conventions, traditions, and sentiments that usually had in them some important truth. (This idea profoundly influenced the Chestertonian William F. Buckley Jr.)

Tomorrow, “Shaw, Scientism, and Darwinism.”