Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

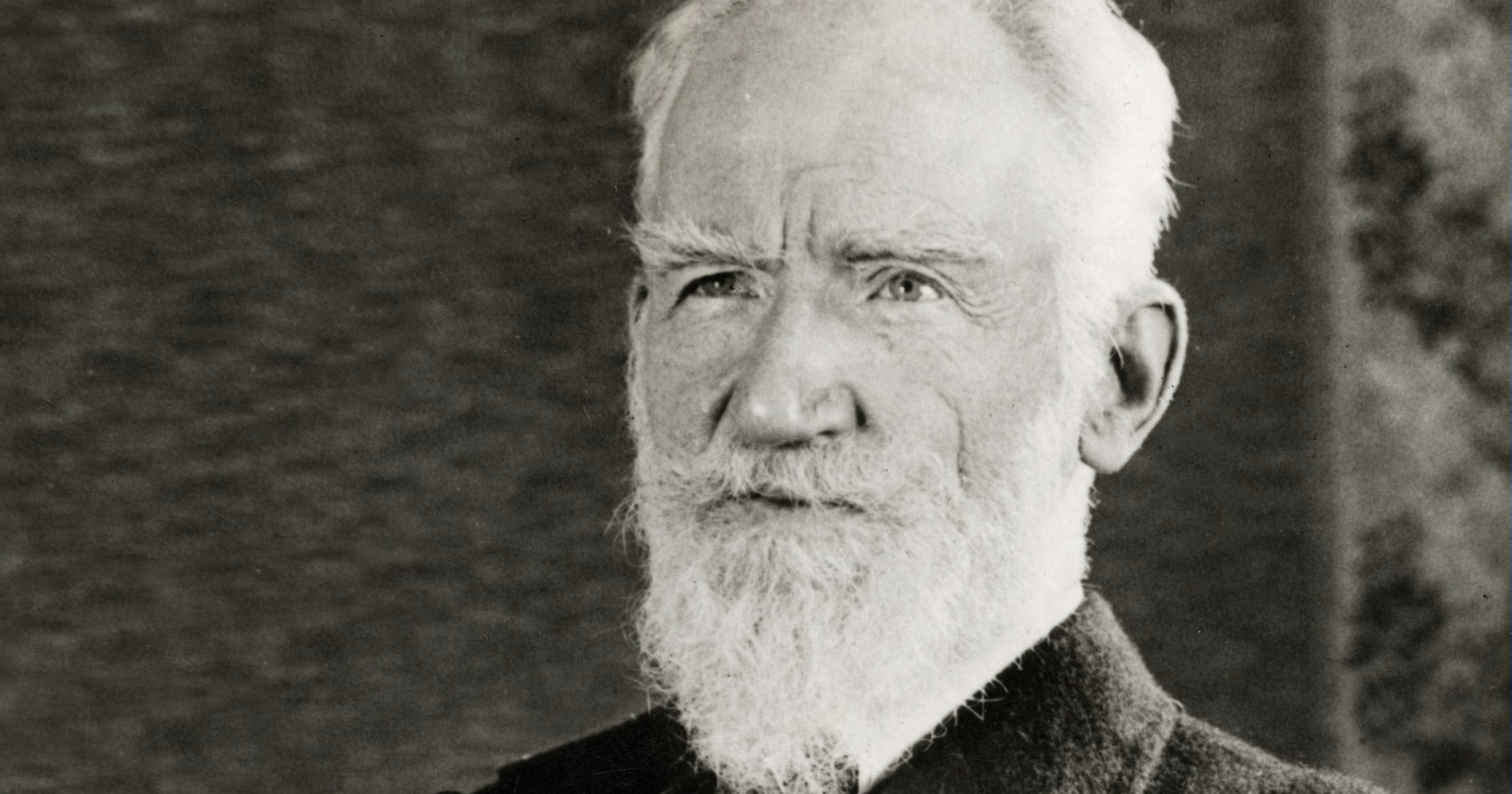

Shaw, Scientism, and Darwinism

Editor’s note: The following, third in a three-part series, is adapted from an essay in National Review and is republished here with permission. Professor Aeschliman is the author of The Restoration of Man: C.S. Lewis and the Continuing Case Against Scientism (Discovery Institute Press). Find the full series here.

Much of George Bernard Shaw’s greatness was properly destructive of illusions and self-interested shibboleths and bromides, what Kant called “the radical evil” — the use of the language of ethics as a screen for self-interest or self-love. An outsider to Victorian England, Shaw saw how post-Christian Great Britain habitually used such screens, and he mocked them with hilarious and hygienic effect. Jacques Barzun claimed that Shaw was in the true dramatic tradition of Aristophanes and Molière, and Shaw himself said, “My business as a classic writer of comedies is to chasten morals with ridicule.” He was proud of reintroducing to English drama “long rhetorical speeches in the manner of Molière.” Barzun called him “a 20th-century Voltaire.”

Ambiguous, Eclectic, and Inconstant

Yet Shaw’s positive criterion by which to measure and ridicule folly and vice was fatally ambiguous, eclectic, and inconstant, as Chesterton pointed out, more in sadness than in anger. Shaw could deplore scientism, what he called “the anti-metaphysical temper of nineteenth century civilization” (preface to St. Joan), and thus excoriate the inhuman and subhuman implications of Darwinism, and he could sincerely invoke the conception of a Godhead immanent in all human beings. His critique of scientistic imperialism in promiscuous, cruel vivisection finds a resonant echo in our time in our better protocols for animal experimentation, as John P. Gluck in his Voracious Science and Vulnerable Animals (2016) has movingly shown.

But often his clear, confident moral rectitude is just a muddle; as his character Barbara Undershaft, the Salvation Army “Major Barbara” of his 1905 play, says after her loss of faith, “There must be some truth or other behind this frightful irony.” Shaw’s close friend Beatrice Webb castigated the play as “amazingly clever, grimly powerful, but ending . . . in an intellectual and moral morass.” The same could be said of a number of the plays — absurd outcomes, without the later, post-Shaw intention of celebrating absurdity (Beckett, Sartre, Pinter, Albee; Tom Stoppard is a salutary exception — Shaw’s true successor). Some of the plays are almost unbearably tedious, such as the vast Back to Methuselah, despite its brilliant prose preface. In a notable attack on Shaw, the actor and playwright John Osborne, who had acted in provincial productions of many of the plays, asserted in 1977 that “Shaw is the most fraudulent, inept writer of Victorian melodramas ever to gull a timid critic or fool a dull public.” It is not difficult to agree with him that the much-praised Candida (1900) is “an ineffably feeble piece” and that “it is hard to think of anything more silly.”

Strangely Pious

Shaw’s biggest box-office success was the poignant, strangely pious St. Joan (1923), written especially for the actress Sybil Thorndike (1882–1976), which made her career. Some of the plays still make powerful reading and seeing — Pygmalion, Androcles and the Lion, and Arms and the Man are marvelous comedies. His prefaces are often lucid and profound, his music criticism expert, eloquent, and memorable — for example, his early championing of Beethoven is deeply moving. His literary criticism is sometimes classic and even lapidary, as in his famous 1912 introduction to Dickens’s novel Hard Times.

But Chesterton was right to think that trying to synthesize Nietzsche and socialism — and ultimately communism — was to produce fool’s gold and destructive illusions. Writing after his own painfully revealing year in Moscow in 1932–33, as a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian, Malcolm Muggeridge, a favored relation of Shaw’s close friends the Webbs, who was raised on Shaw in his London socialist home, deplored Shaw’s fellow-traveling propaganda for Communist Russia, whose reality the acute Shaw failed to recognize in his 1931 guided tour or for the 20 years of his life that remained. Chesterton’s ambivalence about Shaw as man and writer remains a superbly judicious guide to the most influential English-language dramatist of the 20th century; and Chesterton’s own body of writing, in several genres, remains a golden thread by means of which the sanest and most salutary elements of the classical-Christian literary, ethical, and political tradition made their way into the apocalyptic 20th century, and make their way to us.