Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Evolution

Evolution

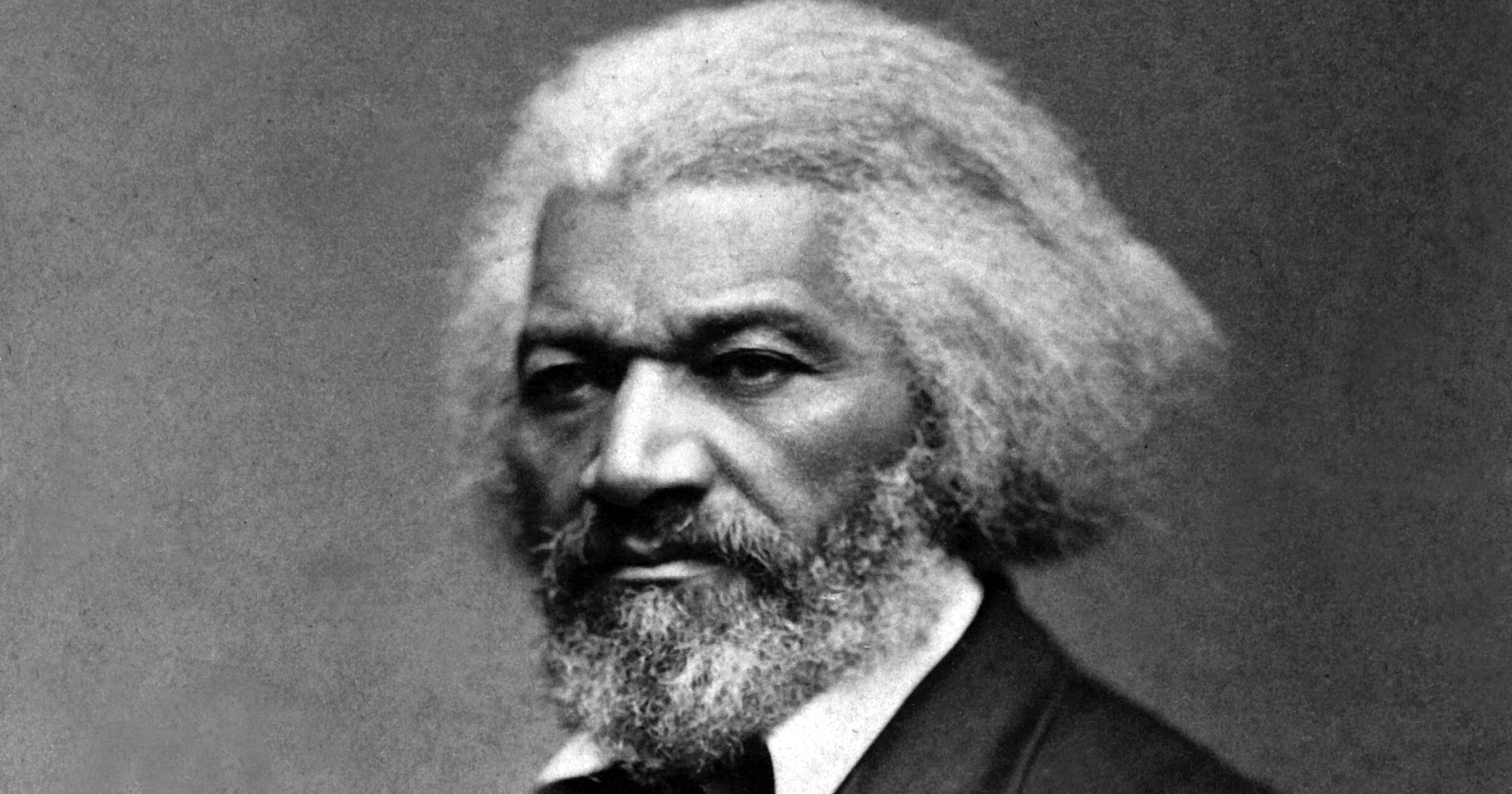

Frederick Douglass, Champion Abolitionist and Former Slave, on Evolutionary Racism

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) in “The Claims of the Negro Ethnologically Considered,” a commencement address delivered at Western Reserve College on July 12, 1854, stated eloquently:

Man is distinguished from all other animals, by the possession of certain definite faculties and powers, as well as by physical organization and proportions. He is the only two-handed animal on the earth — the only one that laughs, and nearly the only one that weeps. Men instinctively distinguish between men and brutes. Common sense itself is scarcely needed to detect the absence of manhood in a monkey, or to recognize its presence in a negro. His speech, his reason, his power to acquire and to retain knowledge, his heaven-erected face, his habitudes, his hopes, his fears, his aspirations, his prophecies, plant between him and the brute creation, a distinction as eternal as it is palpable. Away, therefore, with all the scientific moonshine that would connect men with monkeys; that would have the world believe that humanity, instead of resting on its own characteristic pedestal — gloriously independent — is a sort of sliding scale, making one extreme brother to the ourang-ou-tang, and the other to angels, and all the rest intermediates! [Emphasis added.]

Douglass could make this observation before Darwin wrote Origin in 1859 because such man-to-primate connections had already been suggested in Lamarck’s evolutionary principle of use and disuse and in Robert Chambers’s Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, published ten years earlier in 1844. It was the Reverend Adam Sedgwick who confessed to Charles Lyell that Chambers’s “foul book” had little to recommend it, and he worried about “our glorious maids and matrons” who would read that “they are the children of apes and breeders of monsters.” Interestingly, when Darwin’s Origin appeared Sedgwick thought no more of the effort than he had of Chambers’s Vestiges. He called the book “utterly false & grievously mischievous,” and Darwin even complained that his old mentor “has been firing broadsides” at it.

Freedom’s Champion

There is no reason to suggest that Douglass — always freedom’s champion — felt much differently from Sedgwick. Fact is, Douglass had little to say directly about Darwin’s theory after the Origin appeared; he certainly knew of it and had at least read portions of it, but with emancipation barely won in 1865 and the rise of the Jim Crow South and the KKK he had dragons enough to slay. The appearance of Darwin’s fourth edition of Origin in 1866 probably didn’t even catch his eye. Randall Fuller admits in his piece of Darwinian apologetics, The Book that Changed America (2017), that Douglass “consistently evaded that portion of evolutionary theory [propounded by Darwin] that linked human beings to nonhuman species.” But perhaps that is because he felt his earlier comments were sufficient to establish his position. His commencement speech was quite clear on the matter. If anything Douglass’s comments are much more in line with those of Alfred Russel Wallace’s belief in the special attributes of human beings that he expressed with such passion.

Never a Podium

One wonders what kind of address Douglass would give on Darwin Day — falling tomorrow, February 12 — amidst Black History Month. Rather than quote Darwin, I suspect Douglass would find friendlier company with Wallace who once remarked that all peoples, even the most “uncivilized . . . possessed good qualities, some of them in a very remarkable degree, and that in all the great characteristics of humanity they are wonderfully like ourselves . . . both physically, morally, and intellectually our equals, if not our superiors.” Champions of women’s rights, freedom for the downtrodden, and the extension of true democracy, Wallace and Douglass shared many things — unfortunately, never a podium.