Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

A Modest Invitation to David Sivak

Yesterday I commented on an excellent recent presentation in the Saturday Morning Lectures series by Dr. David Sivak, a physicist at Simon Fraser University. Professor Sivak is an intelligent, articulate researcher with much to offer. I wish him and his team all the best in their endeavors to elucidate the functions of the astounding molecular machines found at the heart of life. In the spirit then of a few modest suggestions to help make the research as fruitful as possible, here is my sincere invitation to Sivak as he moves forward with his great research program.

Don’t Hitch Your Wagon to a Dead Horse

Don’t burden your great research program with Darwin’s mid-1800s view of biology (or any modified descendant of Darwin’s general premise). You don’t need it. It doesn’t help your research.

As an engineer, you know that functional coherent systems are built for a purpose and have to be set up in just the right way. The parts and the pieces and the construction processes are there for a reason. Don’t let evolutionary thinking intrude with its intellectually lazy references to “nature evolved” this system, or that machine “was selected,” or everything came about by sheer dumb luck and some stuff happened to stick. The theory of evolution is simply not a great theory of how engineering works. It doesn’t add anything of value, and only distracts from the good research you are doing.

Drop the Darwin-Speak

Similarly, don’t burden your lectures and presentations and published papers with unnecessary Darwin-speak. As Joe Friday would demand, “Just the facts ma’am.” You have great substance in the research you’re doing. Stick with that and focus on the actual observed evidence. In your next lecture, rather than saying, “We’re going to examine an amazing molecular machine that nature evolved,” just say, “We’re going to examine an amazing molecular machine found in nature.” It’s that simple. Nothing substantive is lost by jettisoning the evolutionary narrative. Indeed, sticking with the observed facts brings clarity and places the discussion on more solid ground.

Similarly, when preparing a paper for publication and the temptation arises to refer to evolution or natural selection, stop and ask yourself what you’re really saying and whether it is germane to the research at hand. Are you really claiming that the system evolved? Can you support that claim with solid evidence? Is it even relevant to the research results you are reporting? If not (as will almost always be the case), just leave it out. Don’t say something like, “Here we elucidate the evolution of ATP synthase,” but instead just say, “Here we elucidate the construction and function of ATP synthase.”

Listen to the Design

A large part of your group’s research goal is uncovering the “fundamental design principles for effective biological function.” Great! Now be willing to acknowledge the implications of that research. There is no more an engineered system without an engineer than there is a book without an author or a song without a songwriter.

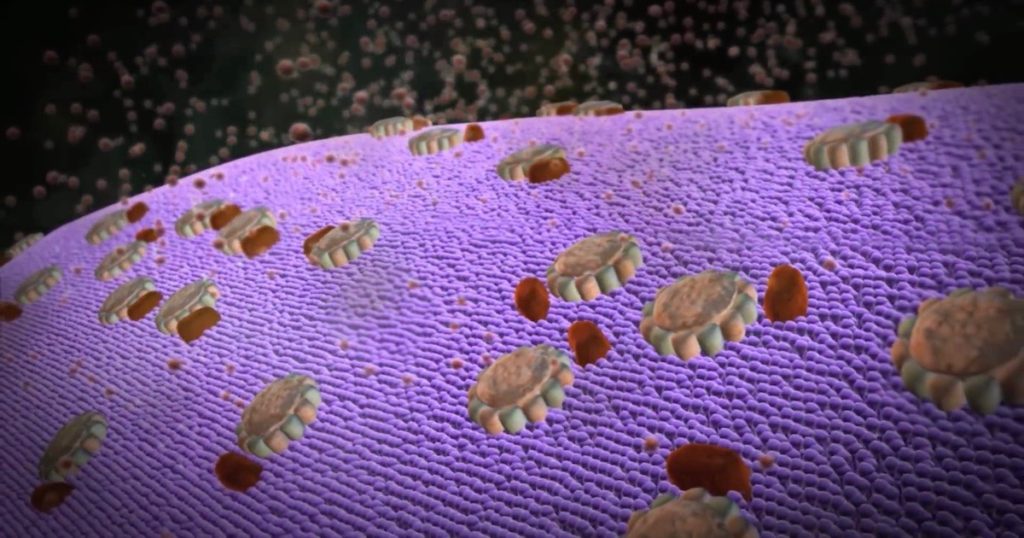

These astounding molecular machines — rotors and motors and pumps quietly, incessantly whirring away at the heart of life — are telling us something profound about their origins. It may be uncomfortable at first to squarely face the implications, but it is an incredibly powerful and exciting discovery. Be willing to accept the implications of your own experimental research, and look forward to a fascinating and lifelong study of the ingenious skill and capability of the real engineer behind life.