Evolution

Evolution

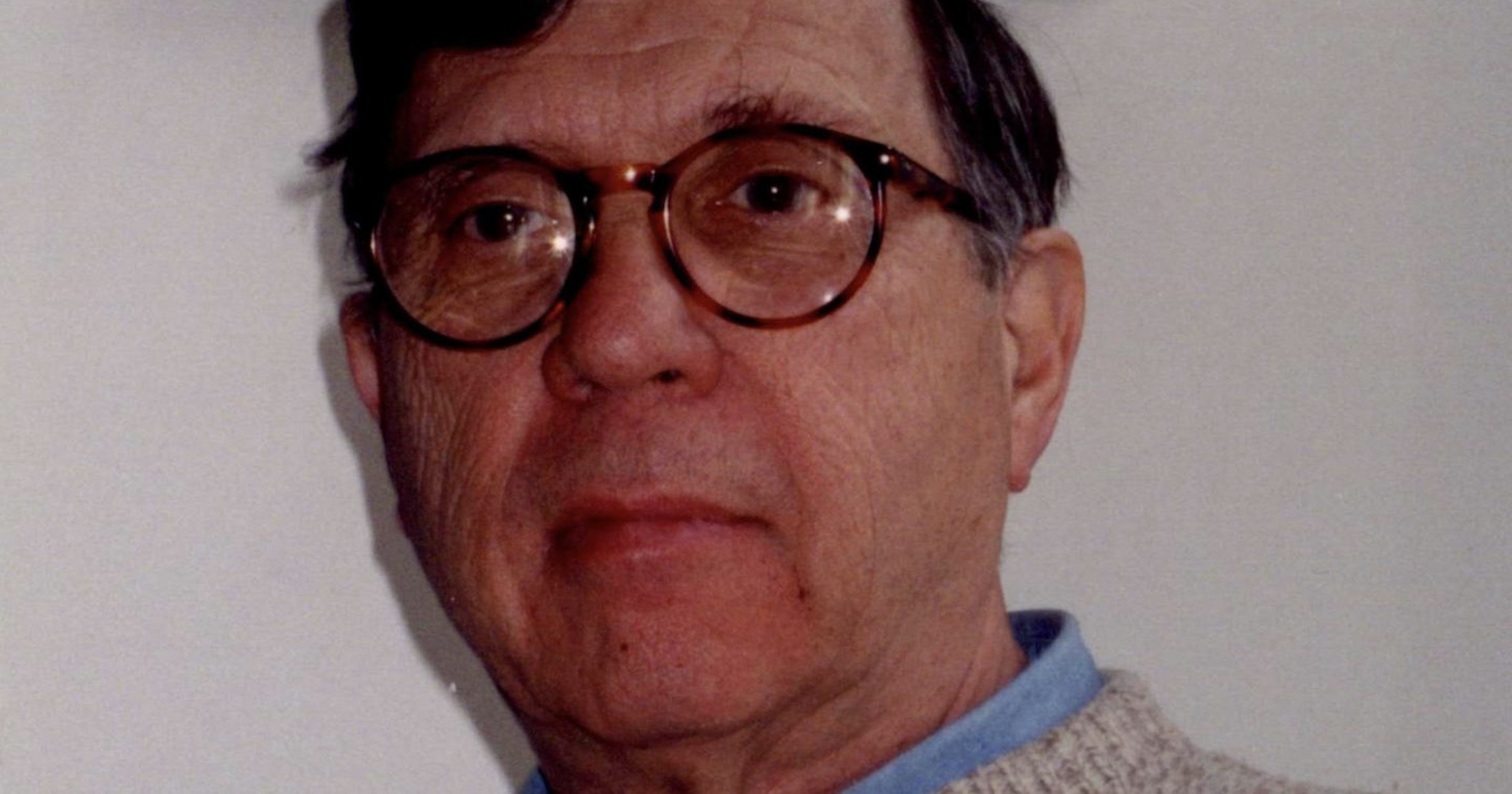

Richard Lewontin (1929-2021), Mensch

David Berlinski humorously scolded me once for using Yiddish phrases in conversation. “Those words should burn in your mouth,” he said — a chastening warning for a Missouri Synod Lutheran boy from Minnesota to hear. But the reason Yiddish words such as tchotcke, kvell, kibbitz, or schnorrer have found a place in English is the tongue of Shakespeare and Updike has no exact equivalent for any of them. What’s the English word for schlmiel? You know: “that guy who always spills the soup on someone else” (the schlimazel, naturally — another Yiddish word with no English counterpart). A language borrows words it does not have, but can use.

And English has no exact equivalent for mensch: a person of honor, integrity, and wisdom, someone you can always count on. Richard Lewontin, professor emeritus of genetics and evolution at Harvard, who died on July 4, was a mensch. I know I am growing older because my heroes are dying, and, since my late teens, Lewontin was one of my heroes. Nearly everything he wrote on biology contained a keepsake insight. I broke the binding of my copy of The Genetic Basis of Evolutionary Change (1974) by steady usage, and the letter “L” in my reprint file is populated mainly with Lewontin articles.

“His Own Counsel”

We do have a phrase in English that captures what I’d most like to say about Lewontin’s scholarship: “He kept his own counsel.” Lewontin was an unapologetic Marxist, a philosophical and political perspective that, whatever its flaws, gave him an independent standpoint from which to critique neo-Darwinian theory. And he did: his 1978 essay on adaptation, for instance, presaged a broader critical analysis by a larger scientific community of central neo-Darwinian concepts such as “fitness.” Lewontin opposed the facile storytelling of much of sociobiology, with its invocation of hypothetical genes for equally hypothetical behavioral traits. The fact that his opposition stemmed in part from his politics is no indictment; his evidential critique holds its value, or stands on its own two legs, independently of the Marxism. Show me the actual data, he would say, or stop the storytelling. Politics count against one in science (or anywhere) when politics is all one has to bring to the table. That would never be true of Lewontin’s work, which will endure.

Precious Space

But let me recount a personal interaction that shows the mensch. From 1991 to 1994, my wife Suzanne and I lived in Boston (Jamaica Plain), while Suzanne was a research fellow at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital. I was writing my dissertation at the time, and obtained borrowing privileges at the library of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), where Lewontin had his famous office — famous for its openness and for the number of distinguished researchers who spent time there as graduate students, post-docs, or visitors.

One day, biologist Michael Donoghue was giving a talk in the common room of Lewontin’s MCZ lab, on some issue in systematics (can’t remember exactly — a topic in methods of phylogeny reconstruction). I arrived to find all the seats already taken, with people standing along the walls and sitting on the floor. Not a situation where it was advisable to arrive even a minute or two late.

As I stood by the lab doorway, craning my neck to see Donoghue, Lewontin — who was sitting right down front, next to where Donoghue was speaking — looked back towards the door and caught my eye. He smiled and pointed to the open space at his own feet. You can sit right here, his expression said. There’s plenty of room. So I squeezed in, sat down, and received an encouraging pat on the back from Lewontin.

I will never forget that moment. Even now, almost thirty years later, his kindness brings tears to my eyes. Space is precious in an overcrowded room. But more valuable to Lewontin was providing an opportunity, by sacrificing his own comfort, for a total stranger to hear a talk properly.

“The name of the righteous is used in blessing” (Proverbs 10:7).