Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Evolution

Evolution

The Racism of Darwin and Darwinism

Editor’s note: The following is excerpted from Chapter 1 of Richard Weikart’s new book, How Darwinism Influenced Hitler, Nazism, and White Nationalism.

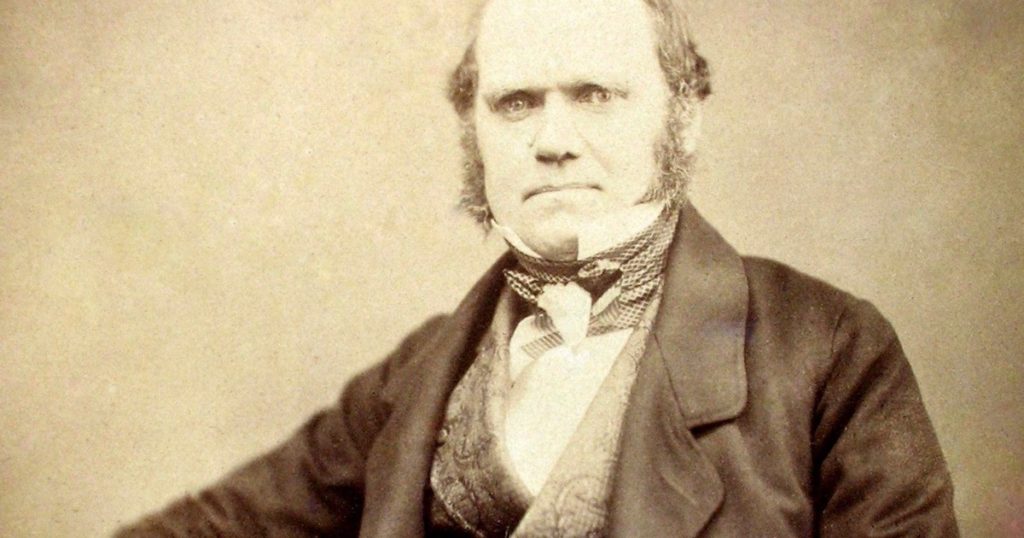

In 1881, toward the end of his life, Charles Darwin wrote to a colleague that the “more civilised so-called Caucasian races have beaten the Turkish hollow in the struggle for existence. Looking to the world at no very distant date, what an endless number of the lower races will have been eliminated by the higher civilised races throughout the world.”1 This was not just some offhand comment unrelated to Darwin’s science. It reflected important elements of his theory of human evolution. Indeed, he articulated this same principle in his scientific study of human evolution, The Descent of Man (1871), where he claimed, “At some future period, not very distant as measured by centuries, the civilised races of man will almost certainly exterminate and replace throughout the world the savage races.”2 Not only racism, but racial extermination was an integral feature of Darwin’s theory from the start.

This is a position that has been articulated by many historians of science.3 Two prominent historians specializing in the history of Darwinism, Adrian Desmond and James Moore, mince no words about the racism inherent in Darwin’s theory. In their magisterial biography of Darwin, they state, “‘Social Darwinism’ is often taken to be something extraneous, an ugly concretion added to the pure Darwinian corpus after the event, tarnishing Darwin’s image. But his notebooks make plain that competition, free trade, imperialism, racial extermination, and sexual inequality were written into the equation from the start — ‘Darwinism’ was always intended to explain human society.”4

A Surprise to Some

It might come as a surprise to some that Desmond and Moore include “racial extermination” in this list, since in a later book, Darwin’s Sacred Cause: How a Hatred of Slavery Shaped Darwin’s Views on Human Evolution, they emphasize Darwin’s humanitarianism and portray his loathing of slavery as a fundamental influence on his view of human evolution.5 However, if one actually reads Darwin’s Sacred Cause, one may be surprised to find that — despite their primary thesis — Desmond and Moore have not at all changed their position about Darwin embracing racism and even racial extermination. They state:

By biologizing colonial eradication, Darwin was making ‘racial’ extinction an inevitable evolutionary consequence…. Races and species perishing was the norm of prehistory. The uncivilized races were following suite [sic], except that Darwin’s mechanism here was modern-day massacre…. Imperialist expansion was becoming the very motor of human progress. It is interesting, given the family’s emotional anti-slavery views, that Darwin’s biologizing of genocide should appear to be so dispassionate…. Natural selection was now predicated on the weaker being extinguished. Individuals, races even, had to perish for progress to occur. Thus it was, that ‘Wherever the European has trod, death seems to pursue the aboriginal’. Europeans were the agents of Evolution. Prichard’s warning about aboriginal slaughter was intended to alert the nation, but Darwin was already naturalizing the cause and rationalizing the outcome.6

Genocide as Progressive Force

Thus, despite stressing Darwin’s opposition to slavery, Desmond and Moore freely admit that he saw genocide — something most of us would consider an even graver evil than slavery — as a progressive force in human evolution. He was thereby justifying the imperialist wars against aboriginal peoples that Europe was conducting in his time. (By the way, Darwin was not unique in embracing both abolitionism and racism, as quite a few 19th-century abolitionists were also racists.)

Desmond and Moore reinforce this point later in the book by quoting from a letter Darwin wrote to Charles Kingsley: “It is very true what you say about the higher races of men, when high enough, will have spread & exterminated whole nations.” Desmond and Moore then provide this explanation of Darwin’s sentiments that he expressed in that letter: “While slavery demanded one’s active participation, racial genocide was now normalized by natural selection and rationalized as nature’s way of producing ‘superior’ races. Darwin had ended up calibrating human ‘rank’ no differently from the rest of his society.”7 Darwin’s theory thus provided justification, not only for racism, but for racial struggle and even genocide.

Victorian Racism: Common but Not Ubiquitous

How had Darwin come to embrace these racist views? As many scholars have pointed out, Darwin’s view that races are unequal is unremarkable. Such racist ideas were circulating widely throughout Europe, both in scientific and popular circles, long before Darwin came on the scene. Many Europeans and Americans used these ideas to justify race-based slavery in the Americas, as well as the European conquest of other lands, such as Australia, New Zealand, the Americas, and later Africa.

However, not all British men and women in the 19th century embraced racism. Some prominent British intellectuals, missionaries, and church leaders believed that black Africans, for instance, were equal to Europeans and only needed the proper education and upbringing to attain the technological sophistication of the Europeans. The famous British missionary and African explorer David Livingstone not only rejected the notion that black Africans were unequal to Europeans, but also devoted his life to showing them love and compassion. He dedicated his energies to fighting against the slave trade, and he even expressed support for the Africans when they fought against British colonial encroachments.8 No wonder Livingstone was beloved by Africans and is still fondly remembered by black Africans.9 One of the most prominent British intellectuals in the 19th century, John Stuart Mill, likewise rejected the idea of racial inequality.10 Mill, like many of his contemporaries, embraced environmental determinism, so he believed that humans were shaped primarily by education and upbringing, not by their biology and heredity. Finally, Alfred Russel Wallace, the co-discoverer of natural selection, also rejected racism and opposed the idea that non-European races were somehow closer to non-human animals than their European counterparts.11

Notes

- Charles Darwin to William Graham, July 3, 1881, Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter no. 13230, University of Cambridge, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-13230.xml. Letter quoted in Francis Darwin, Charles Darwin: His Life Told in an Autobiographical Chapter, and in a Selected Series of His Published Letters (London: Murray, 1902), 64.

- Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, 2 vols. [1871] (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 1:201.

- Most scholars agree that racial struggle is an integral part of Darwin’s account of human evolution, and some even explicitly discuss the role of racial extermination in his theory—see Adrian Desmond and James Moore, Darwin (New York: Joseph, 1991), xxi, 191, 266–268, 521, 653; Robert M. Young, “Darwinism Is Social,” in The Darwinian Heritage, ed. David Kohn (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), 609–638; John C. Greene, “Darwin as Social Evolutionist,” in Science, Ideology, and World View: Essays in the History of Evolutionary Ideas (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981); Peter Bowler, Evolution: The History of an Idea, rev. ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 301; Gregory Claeys, “The ‘Survival of the Fittest’ and the Origins of Social Darwinism,” Journal of the History of Ideas 61 (2000): 223–240. A few scholars, however, emphasize Darwin’s abolitionist sentiments and sympathy for other races, e.g., Greta Jones, Social Darwinism and English Thought: The Interaction between Biological and Social Theory (Sussex: Harvester Press, 1980), 140; Paul Crook, Darwinism, War and History: The Debate over the Biology of War from the ‘Origin of Species’ to the First World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 25–28.

- Desmond and Moore, Darwin, xxi.

- I should note that Darwin’s Sacred Cause is controversial among historians, and most do not agree with its thesis, because even though Darwin’s hatred for slavery is indisputable, it likely had little impact on the formulation of his evolutionary theory.

- Adrian Desmond and James Moore, Darwin’s Sacred Cause: How a Hatred of Slavery Shaped Darwin’s Views on Human Evolution (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009), 149–151.

- Charles Darwin to Charles Kingsley, February 6, 1862, Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter no. 3439, University of Cambridge, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/DCP-LETT-3439.xml. Letter quoted in Desmond and Moore, Darwin’s Sacred Cause, 318.

- Christopher Petrusic, “Violence as Masculinity: David Livingstone’s Radical Racial Politics in the Cape Colony and the Transvaal, 1845–1852,”International History Review 26, 1 (2004): 20–55

- Petina Gappa, “What Nobody Told Me about the Legendary Explorer David Livingstone,” Financial Times Magazine, February 21, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/431696a2-52ac-11ea-90ad-25e377c0ee1f.

- Joshua M. Hall, “Questions of Race in J. S. Mill’s Contributions to Logic,” Philosophia Africana 16, no. 2 (November/December 2014): 73–93.

- Michael Flannery, Intelligent Evolution: How Alfred Russel Wallace’s World of Life Challenged Darwinism (Nashville, TN: Erasmus Press, 2020), 54, 65.