Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Evolution

Evolution

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Aeschliman: The Charles Darwin/John Brown Connection

Literary critic M. D. Aeschliman wrote a terrific review of our colleague Richard Weikart’s new book, Darwinian Racism, for National Review. Professor Weikart, he says,

joins great anti-reductionists such as Barzun, Himmelfarb, Michael Polanyi, and C. S. Lewis as an indispensable resource of knowledge, insight, sanity, and measure in our inevitable and incessant culture wars, whose stakes are very high. Careful, well-informed, and judicious, he reminds us of the depths for good and ill of the human person and of the tragic character of human history when those qualities are not acknowledged and properly understood.

A Historical Turning Point

That’s high and well-deserved praise. Professor Aeschliman opens by pointing out a fascinating historical coincidence.

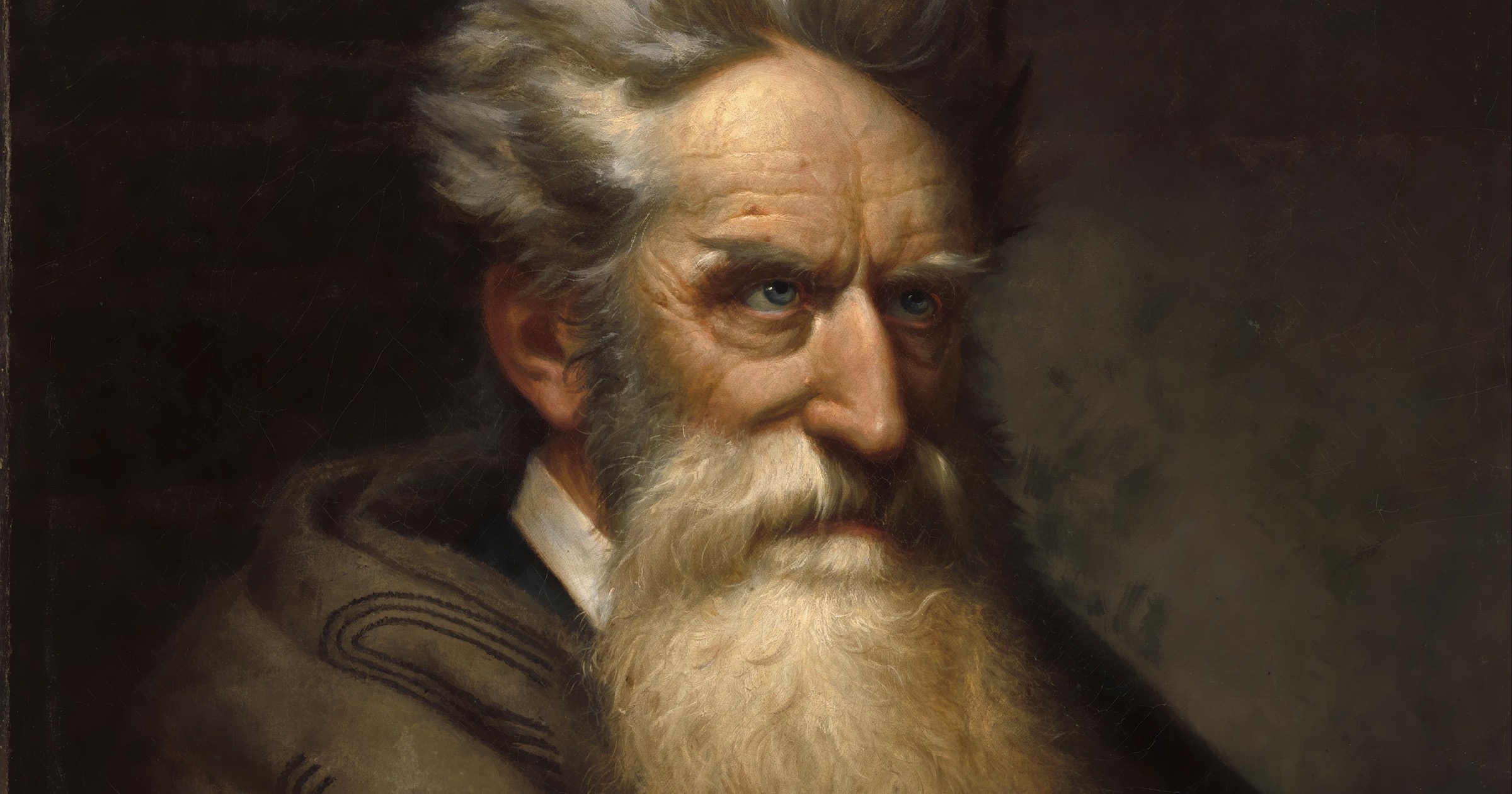

In 1909, on the 50th anniversary of the execution for treason of the radical-Christian abolitionist John Brown, the black intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois published a tribute to him, who in his own time and after his death, during the subsequent American Civil War, had become an inspirational martyr for anti-slavery, anti-racist whites and blacks. But Du Bois was confronted with a logical and rhetorical problem that he struggled to overcome in his tribute. After the Civil War and the death of Lincoln, “those that stepped into the pathway marked by men like John Brown faltered and large numbers turned back,” Du Bois wrote. “They said: He was a good man — even great, but he has no message for us today — he was a ‘belated [Protestant] Covenanter,’ an anachronism in the age of Darwin, one who gave his life to lift not only the unlifted but the unliftable.”

What had intervened between 1859 and 1909 was the emergence and intellectual domination, in the United States and elsewhere, of Darwinian racism, often called “scientific racism,” whose first key document was published in the very year of Brown’s execution, Charles Darwin’s On The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. Brown was captured (by Colonel Robert E. Lee) in his failed insurrection against slavery in Harpers Ferry, Va., in October; Darwin’s momentous book was published on November 24; and Brown was executed on December 2, 1859. The ascendancy of the “scientific racist” conceptualization of Darwin and his many American, British, German, other European, and Japanese disciples was to prove stronger than the Judeo-Christian idealism of Brown and Abraham Lincoln — and of Frederick Douglass and many other noble souls — in the period after the Civil War, especially when married to the melodramatic, hammer-and-dynamite moral nihilism of Friedrich Nietzsche. [Emphasis added.]

Or perhaps “coincidence” is the wrong word. Instead, the year 1859, when Darwin changed the course of science and when John Brown rebelled and died, was a profound historical turning point in thinking about race, opening the door to much devilry. As Aeschliman notes, “Our modern confusion and carnage are largely results of this particular immoralism and secularizing and reducing of consciousness and conscience.”

Weikart’s book, Darwinian Racism: How Darwinism Influenced Hitler, Nazism, and White Nationalism, is out now from Discovery Institute Press.