Evolution

Evolution

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Darwin and the Swinging 1860s

Editor’s note: We are delighted to present a series by Neil Thomas, Reader Emeritus at the University of Durham, “Darwin and the Victorian Crisis of Faith.” This is the third article in the series. Look here for the full series so far. Professor Thomas’s recent book is Taking Leave of Darwin: A Longtime Agnostic Discovers the Case for Design (Discovery Institute Press).

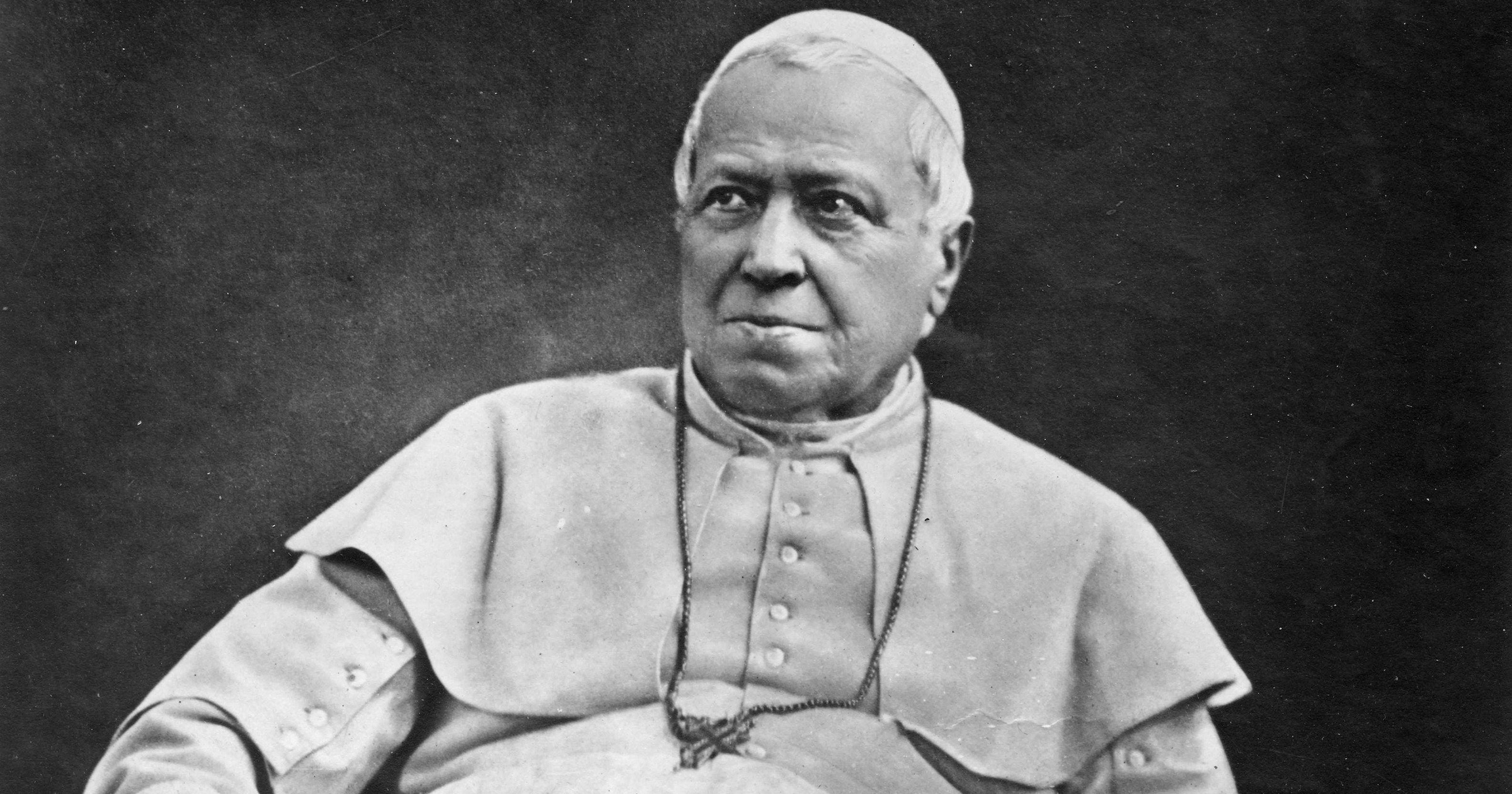

In some respects, the 1860s resemble the 1960s era with the long-haired rabble-rouser Algernon Charles Swinburne somewhat reminiscent of some pop-stars of the Flower Power era.1 The threat which such thinking posed to theistic beliefs was not lost on the Roman Catholic Church when Pope Pius IX convened the First Vatican Council of 1869. Here the doctrine of papal infallibility was passed which together with the Church’s illiberal assaults on science and on the German Higher Criticism2 of the Bible paved the way for the formal Kulturkampf between the Church and German Chancellor Bismarck which raged in Germany throughout the 1870s. The doctrine of papal infallibility clearly created difficulties for those Catholics who placed a high value on personal autonomy and individual conscience, and this has been adduced as one reason why so many should have fallen for the verses of Swinburne.3

The Heart of the Matter

It is at this point that I think we come close to the heart of the matter. A growing number in the mid 19th century simply wished to close their account with the divine since they could not conceive of a God who allowed suffering in the world. It was because it appealed to the growing mindset of disaffection and uncertainty that people were tempted to try to understand the world by the use of exclusively secular criteria. This setting aside of a First Cause may help to explain why a theory such as Darwin’s, at first adjudged scientifically unviable, was nevertheless able to achieve that status of unquestionable shibboleth it later acquired. People began to look for some rallying cry in a closed world of science to explain the world to themselves in the way they wanted in their secularizing age. If this left out of account any final-cause thinking and so offended the strict logic of cause and effect, so be it. Many were in effect prepared to “cut off their nose to spite their face.”

Next, “Evolutionary Theory as Magical Thinking.”

Notes

- The analogy is that of Wilson, God’s Funeral, p. 210.

- The willingness to accept neutral forms of historical and philological analysis to sacred texts was eyed suspiciously as being a silent attack from an ultra-liberal enemy within the Church itself.

- Surprising as it may now appear, some Oxford undergraduates of the time were observed linking arms and declaiming parts of Swinburne’s poems as if in a Greek chorus!