Evolution

Evolution

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Darwin and Theomachy

Editor’s note: We are delighted to present a series by Neil Thomas, Reader Emeritus at the University of Durham, “Darwin and the Victorian Crisis of Faith.” This is the fourth article in the series. Look here for the full series so far. Professor Thomas’s recent book is Taking Leave of Darwin: A Longtime Agnostic Discovers the Case for Design (Discovery Institute Press).

In terms of chronology it is clear that the publication in 1859 of Darwin’s Origin of Species did not cause the Victorian crisis of faith but rather served to confirm the scepticism of those who had already formed anti-theistic attitudes on other grounds. For instance, Matthew Arnold’s poem “Dover Beach” with its famous evocations of an ebbing tide of faith, although not published until 1867, was first conceived in 1851. Tennyson’s In Memoriam where the poet famously describes himself as “faltering where once he once firmly trod” in terms of his personal faith was also conceived before 1859.1

The Closest Chronological Fit

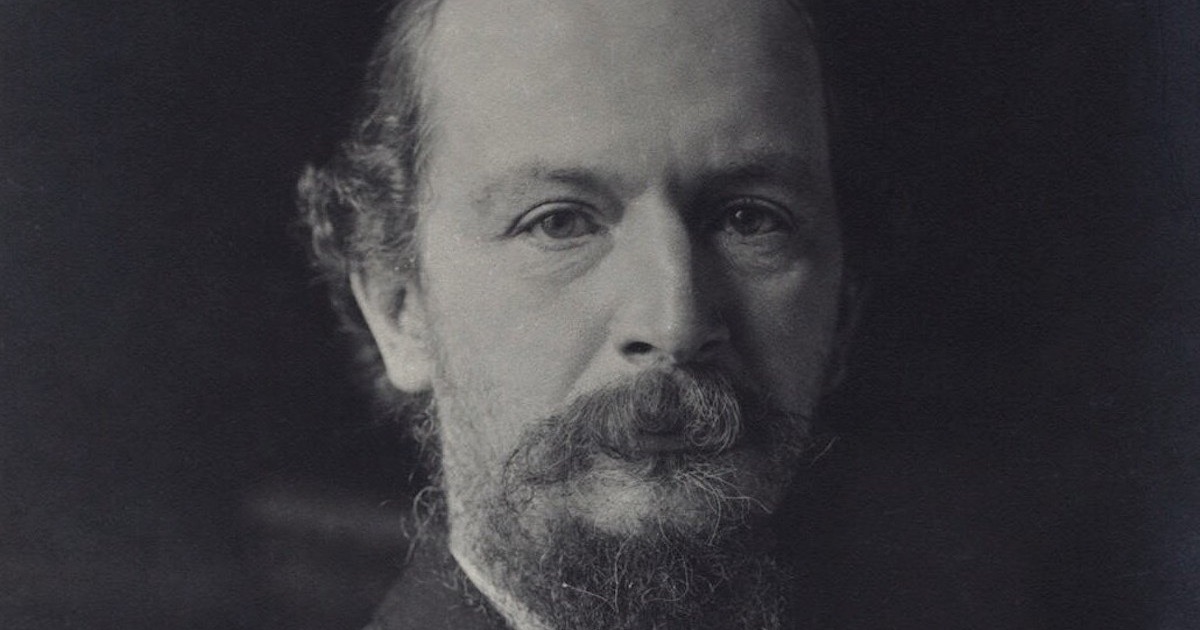

Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909) provides the closest chronological fit with Darwin. Swinburne is not read by many today, and many people may know little of him other than as a melodious versifier with some vague connection to the pre-Raphaelite group of artists. This scarcely does justice to the iconoclastic stance of “the laureate of mid 19th-century unbelief”2 who in his verse drama Atalanta in Calydon has his Classical chorus protest against “the supreme evil, God.” Swinburne, an admirer of the ancient materialist philosopher Epicurus, is thought to have lost his faith while studying in Oxford in 1858-9 (just before the publication of Origin on November 24, 1859). He shared Epicurus’ disdain for the old Greek pantheon, seeing no good reason why humans should worship deities (pagan or Christian) who had not shown themselves worthy of their supposed creatures. Instead, he went back imaginatively in his pagan turn to ancient personifications of natural forces such as Proserpine, goddess of the seasons and natural cycles. Meanwhile, in his Laus Veneris (Praise of Venus) he reprises the medieval Tannhauser legend in which his affirmation of the processes of sex and procreation implies criticism of the sexual puritanism of contemporary denominations of the Christian Church.

A Contrast with Robert Elsmere

Against what he saw as the morbidities of Christian asceticism (he refers to the Christ figure as the pale Galilean turning the world grey with his breath), he foregrounds the robust life force represented by the ancient goddess of love. Bernard Schweizer even sees Swinburne as a precursor of Nietzsche since “they both saw in Christianity a religion in decline and both advocated the extermination of God” — theomachy3 — “in order to infuse new vitality into European culture.”4 Perhaps so, but what is certainly true is that, unlike Mrs. Humphry Ward’s figure of the doubting clergyman, Robert Elsmere, who internalizes his problems with the Almighty by throwing himself into good works in the impoverished East End of London, Swinburne, exulting in his role of enfant terrible to mid-Victorian England,5 externalizes his disaffection by directing his ire directly at what he took to be its proper target.

Next, “Darwin and the Swinging 1860s.”

Notes

- Michael Ruse points out that Tennyson was acquainted with what was in some respects the intellectual precursor and even partial template for Darwin’s Origin, Sir Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830-3). Reading Lyell caused Tennyson to see any meaning in life as confined to just a sequence of endless Lyellian cycles (Ruse, Darwinism and Religion, pp. 34-5).

- The phrase is that of A. N. Wilson, God’s Funeral (London: John Murray, 1999), p. 205.

- A tried-and-tested term in Classical Studies meaning “battling the gods” which I find preferable to Schweizer’s neologism of misotheism (God-hatred).

- P. 92.

- On Swinburne’s hell-raising see Philip Henderson, Swinburne: The Portrait of a Poet (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974).