Evolution

Evolution

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Literary Footnotes to the Book of Job

Editor’s note: We are delighted to present a series by Neil Thomas, Reader Emeritus at the University of Durham, “Darwin and the Victorian Crisis of Faith.” This is the third article in the series. Look here for the full series so far. Professor Thomas’s recent book is Taking Leave of Darwin: A Longtime Agnostic Discovers the Case for Design (Discovery Institute Press).

A novel can present ideas in a way more dramatic, engaging, and hence threatening than countless nonfictional volumes of political philosophy.1

Michael Ruse

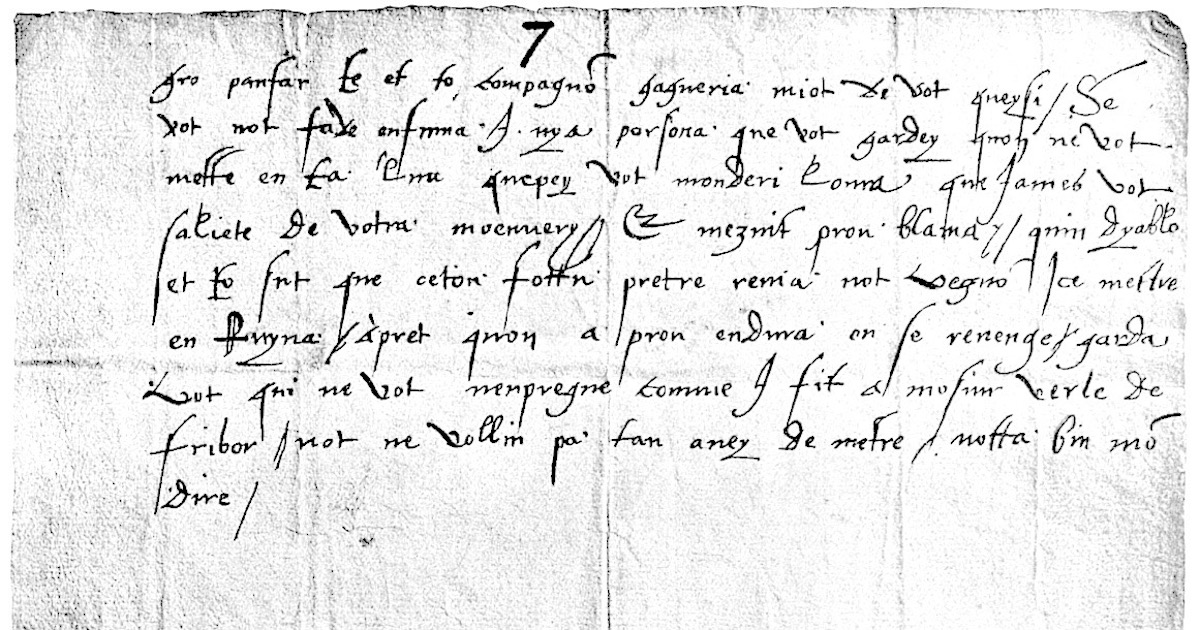

In matters of metaphysical rebellion, it appears that it is the imaginative space of literature that has down the ages provided “the principal conduit for expressions of animosity towards the Almighty.”2 Trials of religious faith have found a particularly honest witness in that form of unfiltered candor that emerges from the solitary practice of transposing private thoughts on to paper. Alec Ryrie gives the historical example of a disaffected Church canon, Jacques Gruet, who in 1547 claimed under the cover of an anonymous missive sent to ecclesiastical superiors (in essence a poison pen letter) that religion was a fraudulent fabrication.3

This claim antedated by a full three centuries the philosophical elaboration of the same contention in Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity (Das Wesen des Christentums). Other veiled expressions of protest have included the early 13th-century German Poor Henry (Der Arme Heinrich), a short verse novella with strong echoes of the Book of Job. Here the eponymous lord of the manor is unaccountably stricken with leprosy, producing the notable response in his feudal dependents that, had it been anybody but God that had stricken their beloved lord, he would immediately become the recipient of their curses.

In the same tradition of coded “protest theology” stands the early 15th-century Death and the Ploughman (Der Ackermann aus Boehmen), an imagined courtroom dialogue of the eponymous plaintiff with the accused, Death, over the premature loss of the ploughman’s wife. The true target of the ploughman’s grief-stricken wrath is of course readily apparent. Similar examples might be adduced from the older literature of many other cultures, but of more immediate relevance to Darwin’s generation were those writers who can be traced in a fairly direct line from, at the beginning of the 19th century, William Blake and Shelley through to Swinburne, James Thomson, and eventually Thomas Hardy at century’s end.

Next, “Darwin and Theomachy.”

Notes

- Michael Ruse, Darwinism as Religion: What Literature Tells us about Evolution (Oxford: OUP, 2017), p. 7.

- Bernard Schweizer, Hating God: The Untold Story of Misotheism (Oxford: OUP, 2011), p. 5.

- Alec Ryrie, Unbelievers, pp. 46-8.