Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Physics, Earth & Space

Physics, Earth & Space

Carl Sagan: “An Intelligence That Antedates the Universe”

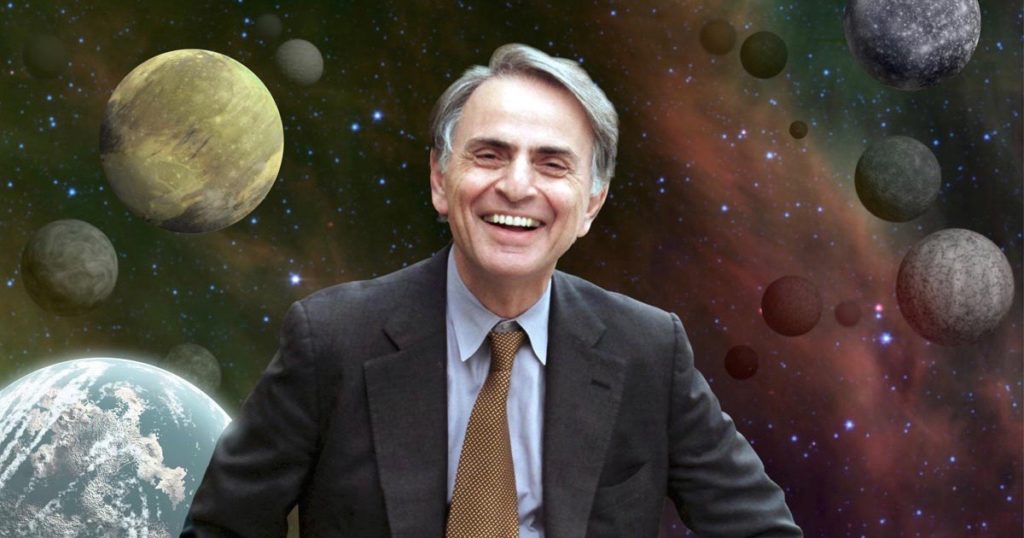

The late astronomer and science popularizer Carl Sagan (1934-1996) is often seen as an exemplar of a certain attitude on the relationship of science and theology: skeptical, anti-religion, pro-naturalism. Abundant evidence supports this view of Sagan, but there are fascinating hints in both his technical and popular writings that Sagan’s understanding of design detection was far subtler and more open-ended than many realize. Like his British contemporary, the astronomer Fred Hoyle (1915-2001), Sagan left evidence that he might well have enjoyed conversations with intelligent design theorists. Such historical counterfactuals are tricky at best, of course, so let’s look at some of the available evidence, and the reader can speculate on her own.

Design Detection in the Galileo Mission

As a scientist on the Galileo interplanetary mission, Sagan designed experiments to be carried on the spacecraft to detect — as a proof-of-principle — the presence of life, but especially intelligent life, on Earth. During Galileo’s December 1990 fly-by of Earth, as the craft was getting a gravitational boost on its way out to the gas giants of the outer Solar System, its instruments indeed detected striking chemical disequilibria in Earth’s atmosphere, best explained by the presence of organisms.

But it was Galileo’s detection of “narrow-band, pulsed, amplitude-modulated radio transmissions” that seized the brass ring of design detection — where “design” means a pattern or event caused by an intelligence (with a mind), not a physical or chemical process. Sagan and colleagues (1993: 720) wrote:

The fact that the central frequencies of these signals remain constant over periods of hours strongly suggests an artificial origin. Naturally generated radio emissions almost always display significant long-term frequency drifts. Even more definitive is the existence of pulse-like amplitude modulations…such modulation patterns are never observed for naturally occurring radio emissions and implies the transmission of information. [Emphasis added.]

Only someone who conceived of “intelligence” as a kind of cause with unique and detectable indicia would bother setting up this proof-of-principle experiment. But it’s the evidence from Sagan’s popular writings that is especially provocative.

Design Detection in Sagan’s Novel Contact

The last chapter (24) of Sagan’s novel Contact (1985; later made into a film [1997] starring Jodie Foster) is an unmistakable example of number mysticism and design detection, using pi — the mathematical constant and irrational number expressing the ratio between the circumference of any circle and its diameter. Entitled “The Artist’s Signature,” the chapter opens with two epigraphs, as follows:

Behold, I tell you a mystery; we shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed.

1 Cor. 15:51

The universe seems…to have been determined and ordered in accordance with the creator of all things; for the pattern was fixed, like a preliminary sketch, by the determination of number pre-existent in the mind of the world-creating God.

Nicomachus of Gerasa, Arithmetic I, 6 (ca. AD 100)

This passage, from the very end of the chapter — and the book — bears quoting. Sagan places the whole section in italics for emphasis:

The universe was made on purpose, the circle said…As long as you live in this universe, and have a modest talent for mathematics, sooner or later you’ll find it. It’s already here. It’s inside everything. You don’t have to leave your planet to find it. In the fabric of space and the nature of matter, as in a great work of art, there is, written small, the artist’s signature. Standing over humans, gods, and demons, subsuming Caretakers and Tunnel builders, there is an intelligence that antedates the universe. [Emphasis added.]

Design’s Narrative Power

Of course, Contact is a novel, not a scientific or philosophical treatise. Sagan was writing for drama (Contact actually started out as a movie treatment in 1980-81). But rather like his contemporaries Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick, Sagan loved to play around with concepts of design detection and non-human intelligence. Their narrative power was undeniable.

And that sentence — “there is an intelligence that antedates the universe” — come on, that’s being deliberately provocative. In any case, mathematical objects such as pi, or prime numbers, have long held a special status as design indicia. The atheist radio astronomer and SETI researcher Jill Tarter, the real-life model for the Elli Arroway / Jodi Foster character in Contact, has said that she would regard the decimal expansion of pi, if detected by a radio telescope, as a gold-standard indicator of extraterrestrial intelligence.

Sagan and Intelligent Design

In 1985, when Contact was first published, intelligent design as an intellectual position was largely confined to the edges of academic philosophy, in the work of people such as the Canadian philosopher John Leslie, and a few hardy souls in the neighborhood of books like Thaxton, Bradley, and Olsen, The Mystery of Life’s Origin (1984).

So Sagan (and Fred Hoyle, whose sci-fi novel The Black Cloud was credited by Richard Dawkins as the book having the greatest influence on him; the story opens with a design inference) could afford to play with notions of design detection, non-human intelligences, and the like. These ideas, which are exciting and full of fascinating implications, posed little risk to the dominance of naturalism in science. Detecting non-human intelligence made for good sci-fi.

When ID appeared to become a real cultural threat, however — as it did starting in the mid 1990s in the United States — the dynamic shifted. Still, while Sagan was anti-religious, he was decidedly not anti-design, in the generic sense of the detectability of intelligent causation as a mode distinct from ordinary physical causation. In any case, he died in 1996, and therefore missed the coming high points of the ID debate. Others took up the skeptical mantle, to make sure that design never found a footing in science proper.

As boundary-pushers, both Sagan and Hoyle caught plenty of flak during their lifetimes. Sagan, for instance, was never elected to the National Academy of Sciences. Both paid a price for their popularity and willingness to write novels toying with non-human intelligences. It is interesting, then, to wonder how Sagan would have responded to ID, as articulated by Michael Behe, William Dembski, Stephen Meyer, etc., and how he might have separated his own views from it.

Historical counterfactuals are a playground. Play fairly, and share the equipment.