Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Wordsworth: The Sage of the Lakes

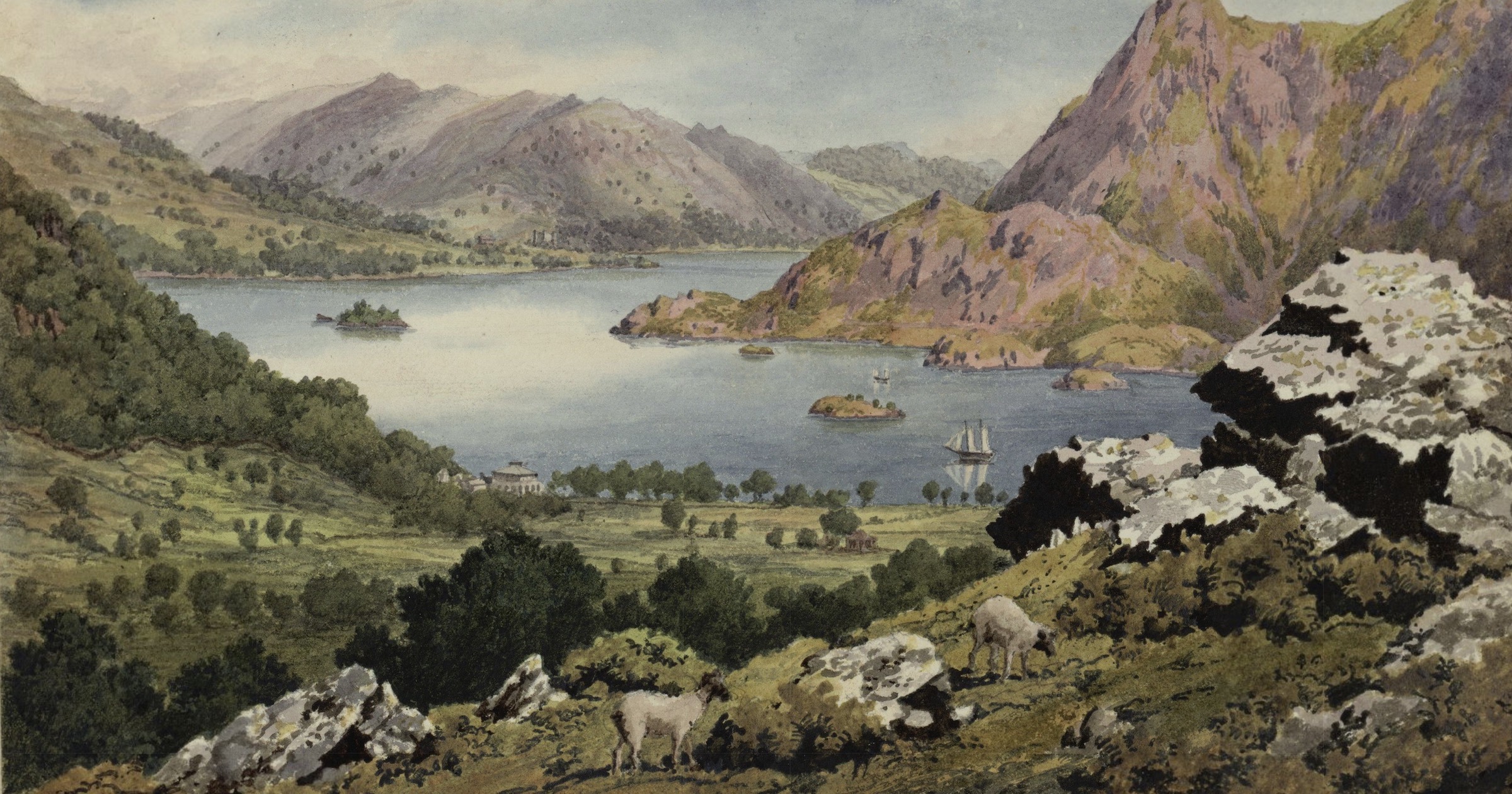

In a series of posts I am exploring the competing visions of nature in the work of William Wordsworth and Charles Darwin (find the full series here). Even in his lifetime Wordsworth was to become something of a guru. Many of the great and good in Victorian England, such as George Eliot and even the convinced religious sceptic Harriet Martineau, visited him in his remote home of Dove Cottage. When John Stuart Mill made his acquaintance with Wordsworth’s work in 1828 he reported feeling free of the low-level depression that had long plagued him.1 The influential critic and chaplain to Queen Victoria, Stopford Brooke, delivered a series of lectures in 1872 in which he praised Wordswoth’s personal view of nature, contrasting it with Alexander Pope’s 18th-century mechanical conception:

But who is this person? Is she only the creation of imagination, having no substantive reality beyond the mind of Wordsworth? No, she is the poetic impersonation of an actual Being, the form which the poet gives to the living Spirit of God in the outward world.2

As F. W. H. Myers justly commented, “Wordsworth’s exponents are not content to treat his poems on Nature simply as graceful descriptive pieces, but speak of him in terms usually reserved for the originators of some great religious movement.”3

A Popular Revolution

Myers made the further point that Wordsworth gave rise not just to a minority group of high-culture admirers but to a popular revolution in ordinary people’s thinking:

Therefore it is that Wordsworth is venerated; because to so many men — indifferent it may be to literary or poetical effects as such — he has shown by the subtle intensity of his own emotion how the contemplation of Nature can be made a revealing agency, like Love or Prayer — an opening if indeed there be any opening, into the transcendent world.4

The fact that Wordsworth’s Guide to the Lakes was a bestseller is in itself an indication of his popular appeal to all kinds and conditions of Britons. As Bate puts it, “In Wordsworth’s youth, genteel tourists came to the Lake District in search of the picturesque. After the advent of the railway, the urban and working classes came in search of Wordsworth.”5

Notes

- For an account of Wordsworth’s later influence see Jonathan Bate, Radical Wordsworth: The Poet Who Changed the World (London: HarperCollins, 2020), pp. 449-479. The most exhaustive account of reception was provided in Robert M. Ryan’s Charles Darwin and the Church of Wordsworth (Oxford: OUP, 2016).

- Stopford Brooke, Theology in the English Poets: Cowper, Coleridge, Wordsworth and Burns [1872] (London: Dent, 1910), p. 79.

- F. W. H. Myers, Wordsworth [1881] (repr. Hamburg: Tredition, 2012), p. 113.

- Myers, Wordsworth, p. 118.

- Jonathan Bate, Radical Wordsworth, p. 464.