Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Evolution

Evolution

My Friend Olufemi Oluniyi and Darwin’s Legacy in Nigeria

Like most white Americans, I have not spent much of my life thinking about or studying Africa and its rich history. I say this with regret.

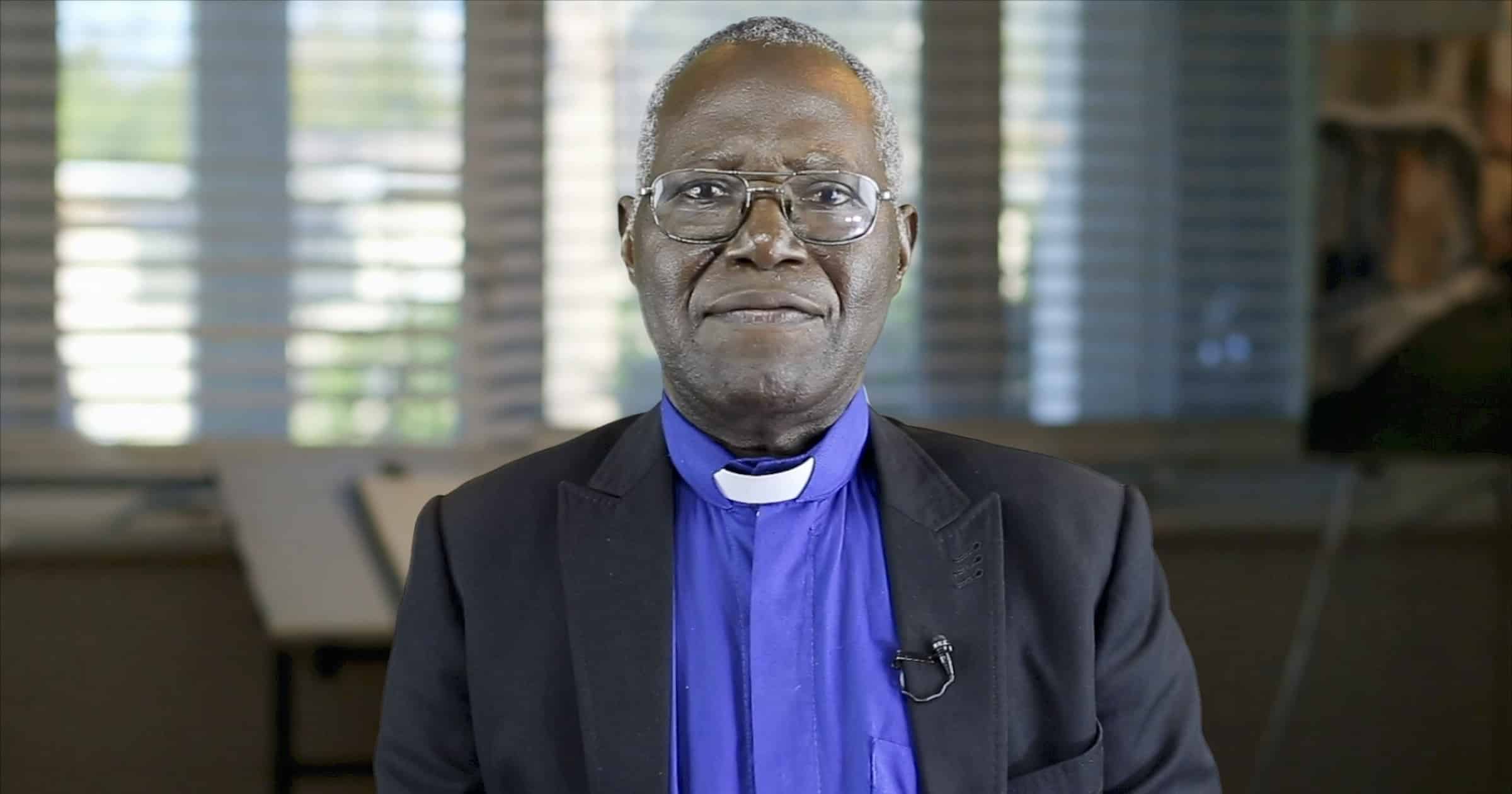

My insularity was challenged when I met the Rev. Dr. Olufemi Oluniyi, author of the new book Darwin Comes to Africa.

Olufemi came to Seattle in the summer of 2017 to participate in Discovery Institute’s C. S. Lewis Fellows Program on Science and Society, which I direct. The trip ended up being Olufemi’s first and only visit to America. Although offered a visiting research professorship at the Catholic University of America years earlier, Olufemi had not been able to accept it at the time.

Eyes and Heart

Olufemi opened my eyes and heart to the importance of Nigeria to Africa, the dynamic role of Christians there, and the importance of Africa to the world. His joy for life, his love for his home country, and his love for his fellow man were contagious.

Olufemi led an influential life. He served as a Christian minister, a college professor and administrator, a journalist, and an activist for peace and non-violence.

He came to participate in our Summer Seminar program because he was especially interested in the impact of Social Darwinism and scientism on society. He had already touched on the topic in his book Reconciliation in Northern Nigeria: The Space for Public Apology, but now he hoped to dig deeper.

Only later did I learn that Olufemi had been filled with trepidation about his trip to America. He knew that we Americans tend to focus on ourselves, and he wasn’t sure his contributions would be valued. He also worried that Discovery Institute might have a blind spot — focusing too narrowly on the scientific debates over Darwinian theory to the exclusion of its social impact.

I’m happy to say that after coming to Seattle he realized he had found kindred spirits.

Investigating Social Darwinism

I learned much from Olufemi that summer, and he awoke in me an abiding interest in both the history and future of Africa. As for Olufemi, he found renewed inspiration to further his investigations of Social Darwinism. By the end of the seminar, he had decided to write a book focusing on the impact of Social Darwinism in Nigeria and refuting its falsehoods. “I announced at the closing session of the seminar my resolve to write a book on Social Darwinism,” he later recalled. “That announcement was a way of self-bolstering my resolve to write and not to renege on the resolve.”

In the years that followed, Olufemi and I exchanged hundreds of emails as he shared his progress in his research. As he worked on his book, he found himself reflecting on connections between his own life and the life of Charles Darwin:

No sooner had I begun my research in earnest than I realized that Charles Darwin and I crisscrossed in our life journeys, with the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, the oldest civic university in the British Empire, as the nexus. On the comparison column, both of us had theological-pastoral training, he at Cambridge University, England, and I at SIM/ECWA Theological Seminary, Igbaja, Nigeria, respectively. Again, in the comparison column, both of us had Edinburgh University education; he in medicine and I in political theology, though at different levels; he at the undergraduate level; I at master’s level. In contrast, sadly, Darwin failed his course, whereas I passed mine.

Nevertheless, both of us seem to have come away with the spirit of adventure that Edinburgh University seems to stamp on students that come within its walls. Indeed, my one-year stint in New College is an abiding inspiration — excellent professors and lecturers sharing knowledge and making themselves available, without a tinge of snobbery, staff that readily cooperate all year round, lunchtime fellowships with academicians who stop by, proximity to the National Library of Scotland, etc….

But “whereas Darwin’s adventure took him down the slippery slope of that pseudo-science of natural selection,” explained Olufemi, “I emerged as an entrenched critic of the rickety notion of Social Darwinism.”

Strangely Silent

Olufemi finished a full draft of his manuscript in June of 2021. Ever enthusiastic, he wrote me at the time: “I ask myself, why can’t this book make it to the New York Times book of the year?” We continued to correspond about his book and other matters into July. Then, strangely, he fell silent. I learned later he had caught COVID-19. On August 2, he died from its complications.

When my father died, I found a verse in the Bible that gave me comfort, and I think it applies equally well to Olufemi: “Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord… they will rest from their labors, for their deeds follow them” (Rev. 14:13).

Olufemi’s friendship was a great blessing in my life, and I wish you could have known him. Through his book, you can get a glimpse.