Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Physics, Earth & Space

Physics, Earth & Space

Rumors of War and Evidence of Peace Between Science and Christianity

Editor’s note: We are delighted to present a series of excerpts from chapters in the recent book, Science and Faith in Dialogue, edited by Frederik van Niekerk and Nico Vorster. You can download a full copy of the book for free by going here.

“The idea of a ceaseless conflict between” science and religion “seems to be an integral part of the public consciousness” (Elsdon-Baker & Lightman 2020, pp. 3–10). So observe two historians in a recent academic anthology about science and religion. The historians go on to argue that this “conflict thesis” is largely faulty while noting that it is “more ingrained in the scholarship than previously imagined” (Elsdon-Baker & Lightman 2020, pp. 3–10). Curiously, proponents of the warfare thesis have focused most of their criticism on Christianity. The impression that Christianity is typically at war with science has been perpetuated by many specific myths about the history of science. In my writing I have debunked six of these myths:

- The Dark Myth: Christianity produced 1,000 years of anti-science “Dark Ages.”

- The Flat Myth: Church-induced ignorance caused European intellectuals to believe in a flat earth.

- The Big Myth: A big universe became a problem for Christianity.

- The Demotion Myth: Copernicus demoted us from the cosmic center and thereby destroyed confidence in a divine plan for humanity.

- The Galileo Myth: Galileo’s clash with the Catholic Church shows how Christianity opposed science.

- The Sceptic Myth: The main heroes of early modern science were sceptics, not believers in God.

While debunking these six myths we will also see evidence for peace between science and Christianity.

The Dark Myth

Atheist biologist Jerry Coyne (2013) once wrote:

Had there been no Christianity, if after the fall of Rome atheism had pervaded the Western world, science would have developed earlier and be far more advanced than it is now.

Did Christianity really drag the West into an anti-scientific “Dark Ages,” a period said to stretch from the fall of Rome to 1450 AD? Let’s see where recent scholarship points (Keas 2019a, pp. 27–40).

Early Medieval Light: 400–1100

The great Church Father Saint Augustine (354–430) laid some of the foundations for science. He contributed to Aristotelian physics in his Literal Commentary on Genesis (Lindberg 2003, p. 17). More broadly, Augustine expressed confidence in our ability to read the “book of nature” because it is the “production of the Creator” (Harrison 2006, p. 118). He insisted we should proceed “by most certain reasoning or experience” to discern the most likely way God established “the natures of things,” a phrase that became a popular medieval book title for works emulating Augustine’s investigative approach (Eastwood 2013, p. 305).

The English monk Bede (673–735) studied and wrote about astronomy in the tradition of Augustine and Ptolemy. Historian Bruce Eastwood called Bede’s book The Nature of Things (c. 701) “a model for a purely physical description of the results of divine creation, devoid of allegorical interpretation, and using the accumulated teachings of the past, both Christian and pagan” (Eastwood 2013, p. 307). Note how Bede’s Christian worldview was compatible with analysis of the natural world as a coherent system of natural causes and effects.

The Light of the High Middle Ages: 1100–1450

Around 1100, European intellectuals graduated from limited translations and commentaries on Aristotle to a more extensive recovery and further development of Aristotelian logic. As refined within a Christian worldview, this advance included a reasoning method well suited to natural science.

Scholars called this form of argument “ratio” (reason), contrasting it with mathematical demonstration. Mathematics begins with first principles thought to be certain and deduces conclusions that carry the same certainty. Ratio, in contrast, uses premises inferred as likely true from sensory experience and then reasons from there to probable conclusions (Burnett 2013, pp. 379–381).

Ratio, a logic appropriate to observational science, enriched the study of motion and change in the natural world. Historian Walter Laird (2013) writes:

The study of motion in the Middle Ages, then, was not a slavish and sterile commentary on the words of Aristotle […] Part of the measure of their success […] is that some of these insights and results had to be rediscovered later by Galileo and others in the course of the Scientific Revolution.

p. 435

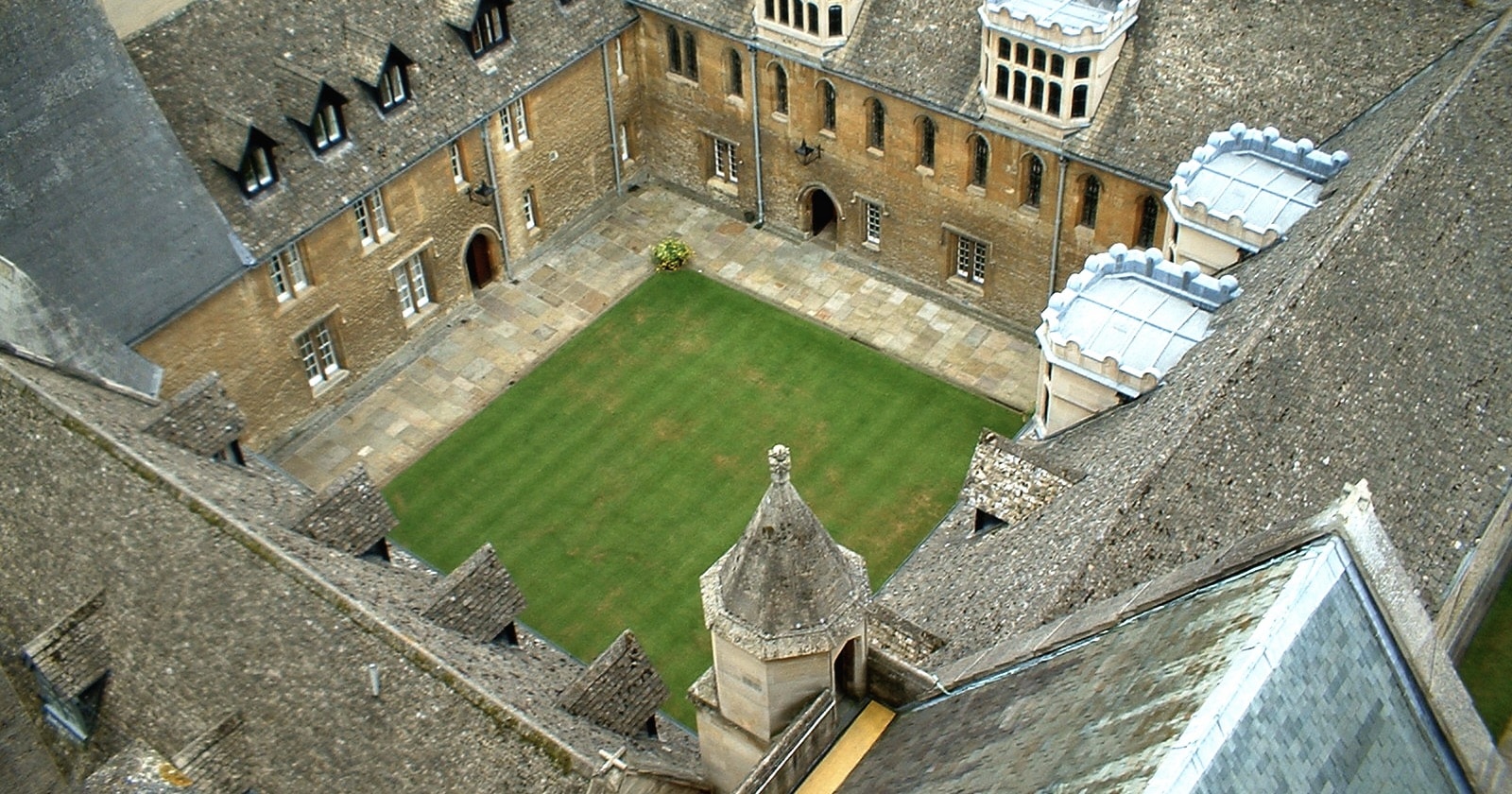

The institution in which most scholars investigated natural motion is also noteworthy — the university. This Christian invention began with the University of Bologna in 1088, followed by Paris and Oxford before 1200, and more than 50 others by 1450. The papacy supported this unprecedented intellectual ferment.

Universities provided additional stimulus to the medieval translation movement already underway, in which Greek and Arabic texts were rendered in the common European intellectual tongue of Latin. This movement greatly outperformed the comparative trickle of imperial Roman translations. If European Christians had been closed-minded to the earlier work of pagans, as the Dark Myth alleges, then it would be difficult to explain this ferocious appetite for translations.

The Franciscan cleric and university scholar Roger Bacon (c. 1220–1292) read much of the newly translated work of earlier Greek and Islamic investigators, including Euclid, Ptolemy, and Ibn al-Haytham, or Alhazen (c. 965–1040). By evaluating them and introducing some controlled observations — what we now call experiments — Bacon substantially advanced the science of light (Lindberg & Tachau 2013, pp. 503–504).

Subsequent authors summarized and reevaluated Bacon’s work, transmitting it through books used in university instruction. That is how it came to the attention of Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), whose account “helped spur the shift in analytic focus that eventually led to modern optics,” in the words of historian A. Mark Smith (2014).

By one estimate (Grant 1984), 30 percent of the medieval university liberal arts curriculum addressed roughly what we call science (including mathematics). Between 1200 and 1450, hundreds of thousands of university students studied Greco-Arabic-Latin science, medicine, and mathematics — as progressively digested and improved by generations of European university faculty.

Contrary to the Dark Myth, medieval European Christians cultivated the idea of “laws of nature,” a logic friendly to science, the science of motion, human dissection, vision-light theories, mathematical analysis of nature, and the superiority of reason and observational experience (sometimes even experiment) over authority in the task of explaining nature.

Medieval trailblazers also invented self-governing universities, eyeglasses, towering cathedrals with stained glass, and much, much more. Although labelling any age with a single descriptor is problematic, the so-called Dark Ages would be far better labelled an “Age of Illumination” or even an “Age of Reason.”

Read the rest by downloading a free copy of Science and Faith in Dialogue here.