Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Evolution

Evolution

Human Origins

Human Origins

The Barbarian Within: Darwinism and the Secular Script for Masculinity

Editor’s note: We are delighted to present a preview adapted from Nancy Pearcey’s forthcoming book The Toxic War on Masculinity. The book will be published on June 27, but you can pre-order now!

Civilization has degenerated into a “mawkish sentimentality,” complained a writer in 1888. “In Heaven’s name, leave us a saving touch of honest, old-fashioned barbarism!”

How did barbarism come to be seen as a positive trait for men — “a saving touch,” a remedy for Victorian sentimentality?…

A new concept of masculinity took hold after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species (1859). His evolutionary theory inspired the idea that, at the core, men are animals — and that to recover their authentic masculinity, men need to reconnect with their inner beast. For example, Zane Grey said that in his Westerns he was trying to recapture the experience of our evolutionary ancestors. “Nature developed man according to the biological facts of evolution,” he wrote. “Something of the wild and primitive should forever remain instinctive in the human race.”

Male writers began to claim that civilization was merely a thin veneer over our animal nature. A book titled Savage Survivals (1916) said, “Civilization is only a skin. The great core of human nature is barbaric.” A book titled The Caveman Within Us (1922) argued that the human organism has only “a slight coat of cultural whitewash, which may be called the veneer of civilization.”

In fact, any man not primitive or barbarian enough risked being judged as a failure as a man. The most prominent psychologist of the age, G. Stanley Hall, remarked that “a teenage boy who is a perfect gentleman has something the matter with him.”

In this chapter, we will investigate the application of Darwinism to human behavior, which is called Social Darwinism. How has it shaped the public discourse on masculinity right up to our own day? How has it contributed to the secular script for the “Real” Man.

The “Blessings” of War

In the nineteenth century, due to industrialization and urbanization, a new word entered the English language: overcivilized. People began to worry that city boys were becoming soft and emasculated. They were no longer the strapping young men produced by harsh pioneer days or rugged farm life. The three principal institutions that dominate early childhood socialization — family, religion, and education — were increasingly staffed and run by women. Men began to cast about for ways to retrieve a sense of robust manhood.

Social Darwinism came in handy in several ways. Take militarism: If life evolved through the struggle for survival, then applying that principle to nations suggests that the way to produce strong, vigorous manhood is through warfare.

“War is a blessing for humanity,” wrote a German anthropologist, “since it offers the only means to measure the strengths of one nation to another and to grant the victory to the fittest. War is the highest and most majestic form of the struggle for existence.” A biologist agreed:

According to Darwin’s theory, war has constantly been of the greatest importance for the general progress of the human race, in that the physically weaker, the less intelligent, the morally inferior or morally degenerate peoples must clear out and make room for the stronger and better developed.

Theodore Roosevelt was a Social Darwinist and famously said in 1895, “The country needs a war.” He argued that the current generation of young men needed to test their mettle in battle:

No triumph of peace is quite so great as the supreme triumphs of war. The courage of the soldier, the courage of the statesman who has to meet storms which can only be quelled by soldierly virtue — this stands higher than any qualities called out merely in times of peace.

G. Stanley Hall even cast militarism as a “manly protest” against the influence of women: “War is, in a sense, the acme of what some now call the manly protest. In peace, women have invaded nearly all the occupations of man, but in war, male virtues come to the fore, for woman cannot go ‘over the top.’” War was depicted not as a necessary evil but as a positive strategy for restoring virile manhood.

Your Inner Barbarian

Social Darwinism was also used to support a sports and fitness craze that swept over the nation toward the end of the nineteenth century. As middle-class Americans left behind the rigorous life on the farm to become a nation of sedentary office workers, they began to turn to sports and exercise to rebuild their physical health. The first tennis court in the United States was built in 1876, the first basketball court in 1891.

Sports were touted not only as a way to get physically fit but also as a way for boys to reconnect with their evolutionary origins. In 1866, the German biologist Ernst Haeckel, a devotee of Darwin, proposed a theory called recapitulation, claiming that each human embryo replays the entire history of evolution (from one-celled organism, to fish, to amphibian, to mammal, to human). Social Darwinists concluded that boys continue the process of evolution by “recapitulating” the history of the human race as they pass from childhood to adulthood.

For example, William Forbush, a child development specialist, wrote a highly influential book titled The Boy Problem (1902) claiming that each boy repeats “the history of his own race-life from savagery unto civilization.” Joseph Lee, a social reformer who founded a movement to build playgrounds in cities, said play arose from an earlier stage of human evolution — from the “barbaric and predatory society to which the boy naturally belongs.” A pioneer in the Boy Scout movement said athletics were reminiscent “of the struggle for survival, of the hunt, of the chase, of war.”

The idea was that even as boys grew up to become refined Victorian gentlemen, they should always retain a core of wildness and savagery. When Ernest Thompson Seton founded the Boy Scouts of America, he said that his goal was to rekindle in boys “the power of the savage.”

Haeckel’s theory of recapitulation was eventually discredited. (He had supported the theory with falsified sketches of embryos; already in his own day, he was accused of fraud.) Yet the idea that humans arose from animal origins and are barbarians at heart was becoming part of the socially constructed definition of manhood.

Darwinian Stories

Darwinism was used to bolster the philosophy of naturalism, the claim that nature is all that exists. Among writers, it inspired a new genre called literary naturalism. Novelists portrayed humans as evolved organisms, governed by the laws of natural selection and survival of the fittest. Émile Zola, a leading theorist of literary naturalism, said he wanted to portray characters as “human animals, nothing more.”

For example, Frank Norris wrote a short story (1893) about a bookish student named Lauth living in medieval France who gets caught up in a riot and ends up killing a man with a crossbow:

In an instant, a mighty flame of blood-lust thrilled up through Lauth’s body and mind. At the sight of blood shed by his own hands all the animal savagery latent in every human being woke within him — no more merciful scruples now. He could kill. In the twinkling of an eye the pale, highly cultivated scholar . . . sank back to the level of his savage Celtic ancestors. His eyes glittered . . . and his whole frame quivered with the eagerness and craving of a panther in sight of his prey.

Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage (1895), often assigned in high school classes, is set during the Civil War. Early in the novel, the main character, Henry, flees from the field of battle. But later he “felt the daring spirit of a savage.” He redeems himself by fighting like a “barbarian, a beast,” a “war devil.”

Jack London is best known for books like The Call of the Wild (1903). But what most people do not know is that, as a young man, London underwent what one historian calls “a conversion experience” to radical naturalism by reading books about evolution. He even memorized passages from Darwin’s books and could quote them by heart, the way Christians memorize Scripture.

Though London wrote about dogs, he intended them as metaphors for humans. In The Call of the Wild, the main character is a dog named Buck, a house pet captured and sold to an Alaskan expedition where he is thrown into a Darwinian struggle for survival. In the Nordic cold, he quickly learns that men and dogs “were savages all of them, who knew no law but the law of the club and fang.”

Eventually, the last tie to civilization is broken and Buck returns to a pre-civilized existence. A literary critic writes, “Ideal manliness thrives in Buck only because he becomes less and less human, more and more wild.”

Theodore Dreiser, author of American classics such as Sister Carrie, likewise underwent a naturalistic rite of passage by reading books about evolution. He wrote that Darwinism blew him “intellectually to bits,” destroying the last vestiges of his Catholic upbringing. He intended his novels to show that all human “ideals, struggles, deprivations, sorrows, and joys” were nothing but products of chemical reactions in the brain. He called them “chemic compulsions.” The literary naturalists used fiction to promote a Darwinian worldview that reduced humans to products of evolutionary forces.

The Thin Veneer of Civilization

The literary naturalists treated the wilderness as an arena where men could reaffirm their masculinity. As one historian explains, the wilderness was seen “as a source of virility, toughness, and savagery — qualities that defined fitness in Darwinian terms.”

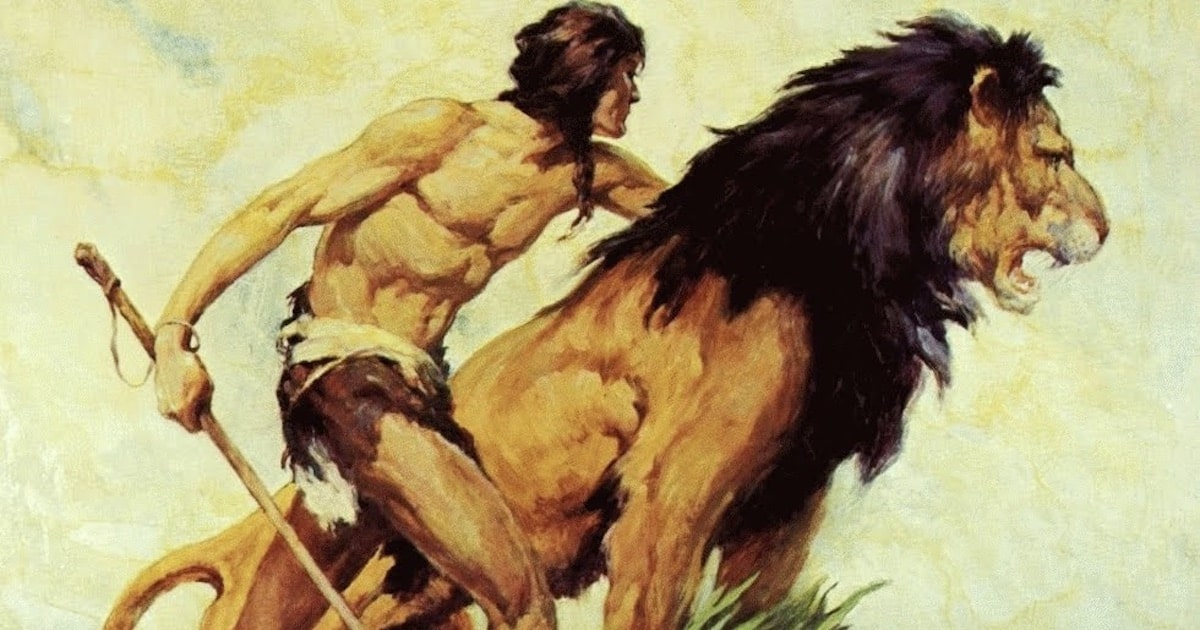

Edgar Rice Burroughs set his immensely popular Tarzan series (1912) in the African jungle. Because of Tarzan’s wild upbringing, he avoids the debilitating forces of civilization, possessing the power and strength of primitive manhood. Even after mastering European customs and languages, he prefers to “strip off the thin veneer of civilization” (as Burroughs puts it) and dress in a loincloth of animal hide, eating raw meat that he has killed himself. In Tarzan of the Apes, he tells Jane, “I am still a wild beast at heart.”

The message of the Tarzan books, says sociologist Michael Kimmel, is that “descending the evolutionary ladder is the only mechanism to retrieve manhood.”

This is a severely stunted, shrunken, truncated view of human nature. From the time of the classical Greeks and Romans, virtue had been defined as the restraint of the “lower” passions by the “higher” faculties of reason, spirit, and moral will. But Darwinism was taken to mean that humans had triumphed over the other species not by reason and moral restraint but by the fierce, fighting urges. In a stunning reversal, the animal passions and instincts were held up as the authentic self.

The secular script for manhood was redefined as crude and combative, governed by the biological instincts for lust and power.

Many of the literary naturalists created rollicking adventure stories that are great fun to read. One of our sons devoured the Tarzan books. But Christians should always read with their worldview antennae poised to pick up the story’s underlying message. A Darwinian worldview furthered secular ideas of what it means to be a man.

The earlier ideal of the Christian gentleman had urged men to live up to the image of God implanted in them. By contrast, the Darwinian worldview urged men to live down to their presumed animal nature — to compete in the ruthless struggle for dominance and power. The “Real” Man was being defined in increasingly toxic terms.