Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Physics, Earth & Space

Physics, Earth & Space

Eat or Be Eaten: Excerpt from New DI Press Novel for Young Adults

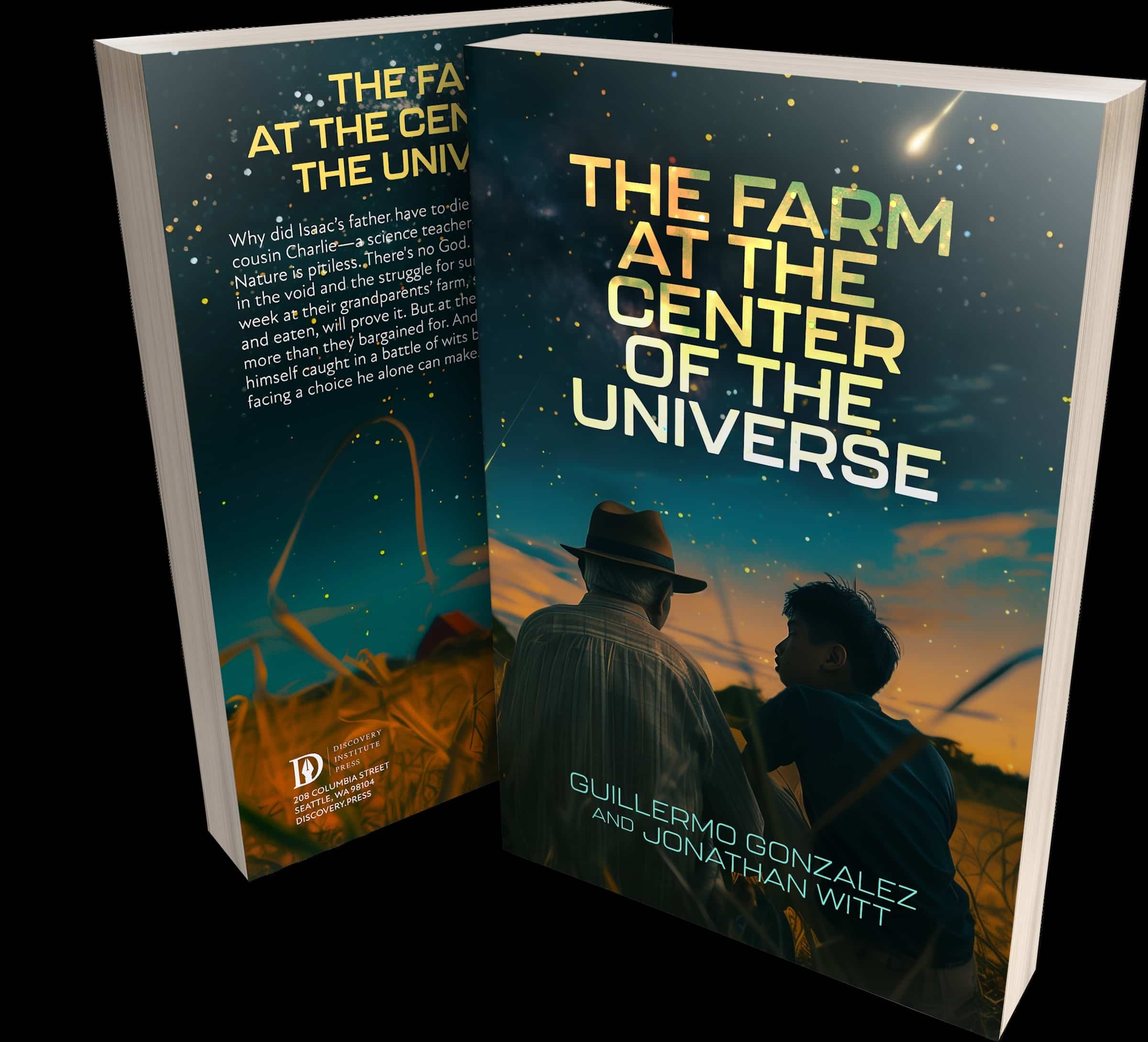

Editor’s note: We are delighted to welcome the publication of The Farm at the Center of the Universe, by Guillermo Gonzalez and Jonathan Witt, the first novel for teens and young adults from Discovery Institute Press. What follows is an excerpt from Chapter 1, “Eat or Be Eaten”:

Isaac watched out the car window as the tall buildings and busy streets of Minneapolis gave way to farmhouses and fields of grain. It was the first day of summer break and his first trip outside the city in forever. It was also six months to the day since his father had died of cancer. The good and the bad were at war in his head.

He was excited and depressed. Happy and sad. He was imagining where the road ahead would take him. And he was fixated on that winter day when he and his mother, brother, and sister stood around the hospital bed and listened helplessly as the beats on the heart rate monitor slowed, slowed, slowed, and then the flatline and the long beep, calling the nurses to rush in and witness another death.

Isaac shook himself back to the present. “Jacob and Becca really wanted to come,” he said, trying to distract himself. “Mom wouldn’t let them.”

From the driver’s seat Charlie checked his side view mirrors, the skin creasing on his thick sunburned neck as he turned first one way, then the other. Charlie was Isaac’s cousin, but he was so much older than Isaac that he was more like an uncle.

“She made the right call,” said Charlie. “For once. They’re not old enough. This is your rite of passage. Like with the Indians. Back in the day, when it was time for an Indian boy to become a man, he got sent out into the wild alone. Little brother didn’t tag along. Baby sister didn’t tag along. Your food didn’t arrive magically from the supermarket, plucked and packaged. You learned to kill and eat. To be a man.”

Isaac turned his face away so Charlie wouldn’t see him roll his eyes. It wasn’t as if Isaac was about to trek across the Rocky Mountains, tomahawk in hand. He was going to spend a week on his grandparents’ farm, eating his grandma’s home cooking and sleeping in a giant feather bed. It wasn’t exactly the wild frontier.

“Being a man means toughening up,” said Charlie, moving seamlessly into his favorite theme. “Life is hard and then you die. Suck it up or ship out. If you’re not a winner, you’re a loser. Don’t be a loser. If you’d been raised by your Asian mom — a ‘tiger mom’— you’d get this. They don’t coddle their kids. Push, strive, drive. Life is a contest. They get it.”

Isaac had lost count of the number of times Charlie had alluded to Isaac’s mythical no-nonsense “tiger mom.” Charlie was generally suspicious of nurturing of any sort, infant or otherwise, and had built up the legend of Isaac’s biological mom to precisely match Charlie’s view of the world. So extreme was Charlie in this regard that Isaac was a little surprised the man had never sung the praises of the orphanage in China that Isaac had been rescued from. No coddling there, that was for sure. The orphanage was so understaffed that the babies were barely ever held and were left crying with dirty diapers for hours at a go.

Or so Isaac had been told by his parents. He had no memory stretching back that far. No memories of China or the orphanage.

In one of his earliest memories — he was three or four — he was sitting in the bleachers with his parents at a high school football game, watching his big cousin Charlie flatten the other team’s quarterback. Flatten, roar. Flatten, roar. Now Charlie was both teacher and coach at Isaac’s school, where he preached the gospel of get tough or get eaten. It was Charlie’s hobbyhorse, and he rode it every day.

In science class, Mr. Charlie (as Isaac had to call him at school) preached Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection — survival of the fittest. He never wearied of telling the class that humans and every other plant and animal — all life — evolved from a tiny microbe. And before that there was the evolution of Earth and the universe — every bit of everything in nature the product of mindless evolution. “Evolution is all about blind forces and dumb luck,” Charlie would say, “weeding out the weak so the strong can thrive and evolve.”

As for God? Ha. “There’s no magical invisible grandfather in the sky,” Charlie would tell the class. “There’s no kindly bearded sky god coming to rescue you. There’s just nature. And nature doesn’t care about your feelings. Nature doesn’t care about your survival. Nature just does what it does, with no regard for you. So, you’d better be ready.”

That was science class with Mr. Charlie. In PE, Coach Charlie put Darwin’s survival of the fittest principle to work, weeding out the weak and lazy and asthma- afflicted with endless sports drills and tests of fitness. To Charlie, every PE kid was a pathetic little snowflake until proven otherwise. Half of Isaac’s friends were terrified of Coach Charlie. The other half wanted to be just like him.

Now Charlie was droning on about how their grandfather would have Isaac up at the crack of dawn, and if Isaac couldn’t cut it, Grandpa would ship him home to mommy mid-week.

But then he stopped mid-sentence and, grinning, swerved the car toward a wake of buzzards picking at a mangled piece of roadkill on the shoulder. The birds rose, flapping, to avoid the car. By the time Isaac turned to look back at them, the buzzards had already settled back to their feast. The remains of a coyote.

“Nature red in tooth and claw,” Charlie said happily. “You live or you die. You eat or get eaten. Winner takes all.”

So Dad was a loser, Isaac supposed, at least in Charlie’s view. Just like the coyote. You won the game of life, until you lost. And Dad had lost.

After Dad died, Isaac had gone numb. He hadn’t felt happy, and he hadn’t felt sad. Just numb. Then on New Year’s Eve they were lighting fireworks in the backyard, and Becca — who was only six years old at the time — didn’t seem to get that the tip of the punk they were using to light the firecrackers was hot enough to burn.

“Watch out,” Isaac said automatically, reaching to tip the hot end of the punk away from her hand.

She yanked away. “You’re not my daddy.”

“Fine,” said Isaac, shrugging. “Burn yourself. What do I care?”

Becca flinched, her face going slack the way it did when she was startled. Isaac knew he ought to feel a little ashamed of his harsh remark, but he didn’t. He didn’t feel anything at all.

That’s when it hit him — his dad — his strong, kind father — was dead and wasn’t coming back. In his place there was a hole in the universe, and through that hole a cold, dark wind blew. At that moment he couldn’t help but think that it was just like Charlie always said — the universe doesn’t care if you hurt. The universe doesn’t care, period. It has no emotions.

And for a long time, neither did Isaac. The first emotion to return was anger — anger that his dad had left them. Now Isaac didn’t know what he felt. Everything was all tangled.

Charlie slowed and turned off the interstate onto a smaller highway. Before long the flat land gave way to deeply rolling plains. Each time they crested a rise, Isaac had a broad view of cloud shadows gliding lazily over bright green fields interspersed with lonely groves of sugar maple, sycamore, red cedar, and oak.

Isaac had never been to his grandparents’ farm. He wondered what it would be like. It was where his grandma had grown up, but then she’d gotten married and moved away, and her bachelor brother had eventually taken over the place. Sometimes Uncle Fred came to family gatherings, but he never invited anyone out to the farm. Then he died, right before Isaac’s dad got diagnosed with cancer.

So, Grandma had lost her brother and her son, but gained a farm. Did that make Grandma a loser or a winner?

Looking for a cheerier track to point his mind down, he turned his thoughts to the particulars of the farm. Would there be a big red barn, cavernous and a little spooky inside? Would there be cornfields? A four-wheeler? Horses to ride? Were there cows, pigs, chickens?

He could have asked Charlie, but then Charlie would describe what each animal meant in practical terms — eggs, meat, milk. Isaac wanted to know whether it was fun or scary to ride on a running horse, to drive a giant combine, what it was like to milk a cow, whether he might actually see an egg pop out of a chicken’s butt. For any of that, Charlie just wasn’t your go-to guy.

No More Naps

Isaac woke with a start.

“No more naps for a week,” Charlie boomed merrily from the driver’s seat. “Grandpa’s about to make a man of you.”

Blinking, Isaac glanced at the dashboard clock. He’d been asleep for an hour. They had turned off the state highway onto a dirt road. Behind them rose a dust cloud, tracing the car’s passage like a jet plane’s vapor trail.

Given Charlie’s announcement, Isaac expected to see his grandparents’ farmhouse up ahead any moment. But no, they drove on for several more minutes, with Charlie drumming on the steering wheel and humming some tuneless ditty.

Every time they cleared a rise, Isaac looked for the farmhouse, but each time it was only an empty field or a solitary grain silo or an old, abandoned homestead.

And then, coming around a sweeping bend in the road, there it was! A snug two-story wooden farmhouse surrounded by trees and — yes — a big red barn.

And now Isaac could see them — Grandma and Grandpa waiting on the front porch, getting up from their rocking chairs and waving at the approaching car.

Charlie pointed the car into the gravel driveway, and before he even had it in park, Isaac jumped out and bounded toward the porch.