Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Does Human Exceptionalism Require Intelligent Design?

Our friend and colleague Wesley Smith’s work is not only brilliant and full of tireless moral energy, he also makes you think. His current article at First Things, “More than ‘In God’s Image,’” raises a provocative question. Can the belief in humanity’s exceptional status in the cosmos be sustained on the basis of “blind evolution,” just as it can on the basis of intelligent design?

Wesley says yes:

A belief in human exceptionalism, on the other hand, does not depend on religious faith. Whether we were created by God, came into being through blind evolution, or were intelligently designed, the importance of human existence can and should be supported by the rational examination of the differences between us and all other known life forms.

After all, what other species in known history has had the wondrous capacities of human beings? What other species has been able to (at least partially) control nature instead of being controlled by it? What other species builds civilizations, records history, creates art, makes music, thinks abstractly, communicates in language, envisions and fabricates machinery, improves life through science and engineering, or explores the deeper truths found in philosophy and religion? What other species has true freedom? Not one.

He argues that advocates of human exceptionalism need to get beyond the theistic language that speaks of humans as being created “in God’s image.” That will work with religious believers, but not with others.

Wesley made me think with his article — but after consideration, I disagree with him on one point. Human exceptionalism may not be excluded by the idea of blind evolution, but it’s undercut and weakened by it.

Only the deluded would fail to see that men and women are more gifted in certain of our capacities than are other animals, and that notable among those are our intellectual abilities and moral drives. We’re exceptional in that respect. Even an individual like Mary “I want a Lamborghini” Gatter of Planned Parenthood would, I’m sure, agree that human civilization far outstrips chimp civilization. For one thing, we have Planned Parenthood clinics, while chimps do not. Yet this doesn’t stop such a person as Dr. Gatter from harvesting unborn human beings in the womb and marketing the pieces as you might with any livestock.

It’s the question of whether that “more” really matters that cuts to the heart. If it is just blind, undirected churning that gave us our gifts, I’m not sure it does matter in any ultimate sense. We are unique, sure, but then only by the luck of the draw. Does that impose higher responsibilities on us, toward animals or toward other human beings? Maybe, but the force of the idea is considerably attenuated under a Darwinian evolutionary perspective.

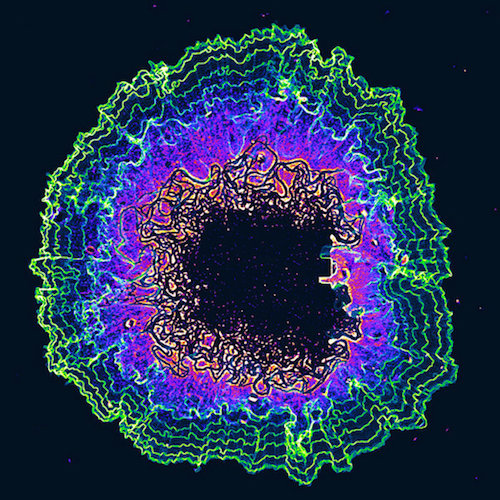

I would also submit that the evidence as it pertains to moral capacities just looks different depending on whether you come to it from an evolutionary or design vantage. Consider this new research in Nature that seeks to attribute moral drives to bacteria.

Far from being selfish organisms whose sole purpose is to maximize their own reproduction, bacteria in large communities work for the greater good by resolving a social conflict among individuals to enhance the survival of their entire community.

It turns out that, much like human societies, bacterial communities benefit when they can balance opposing needs within the group.

The discovery of this unusual behavior among bacteria in large communities, detailed in a paper in the July 22 advance online publication of Nature, comes not from any inherent altruism among the bacteria. Instead, it “emerges” spontaneously from the community in which the bacteria grow.

“It’s an example of what we call ’emergent phenomena’,” explained G�rol S�el, an associate professor of molecular biology at UC San Diego who headed the research effort.

Our other friend Denyse O’Leary at Uncommon Descent observes, “We didn’t know bacteria had morals.” Remember, that is not chimps they’re talking about — it’s microbes, communities of which join together to form a protective “biolfilm.” Which results from what? Blind evolution. More:

“We developed new techniques to precisely measure biofilm growth, and then quantitatively perturbed the system,” said S�el. “And what we found was that the metabolic pathway in question may have been selected for this process by evolution because it involves a small molecule, ammonium, which can diffuse, that is, can get in and out of the cell quickly and can be shared among bacteria.”

I agree with Wesley that arguing effectively for human rights and human status cannot and need not depend on assertions from traditional religious faith. But intelligent design doesn’t require or imply theism. After all, a deist like Thomas Jefferson could still be, in the scientific terms of his time, an ID advocate, as he was.

What ID does do is suggest that our moral capacities have a goal, a purpose, beyond ourselves. Whoever or whatever the source of design may be, it certainly transcends us. That recognition infuses our exceptionalism with urgent and objective meaning.

Image credit: Bacterial biofilm community, by S�el Lab, UC San Diego.