Neuroscience & Mind

Neuroscience & Mind

Artificial Intelligence Understands by Not Understanding

I’ve been reviewing philosopher and programmer Erik Larson’s The Myth of Artificial Intelligence. See my two earlier posts, here and here.

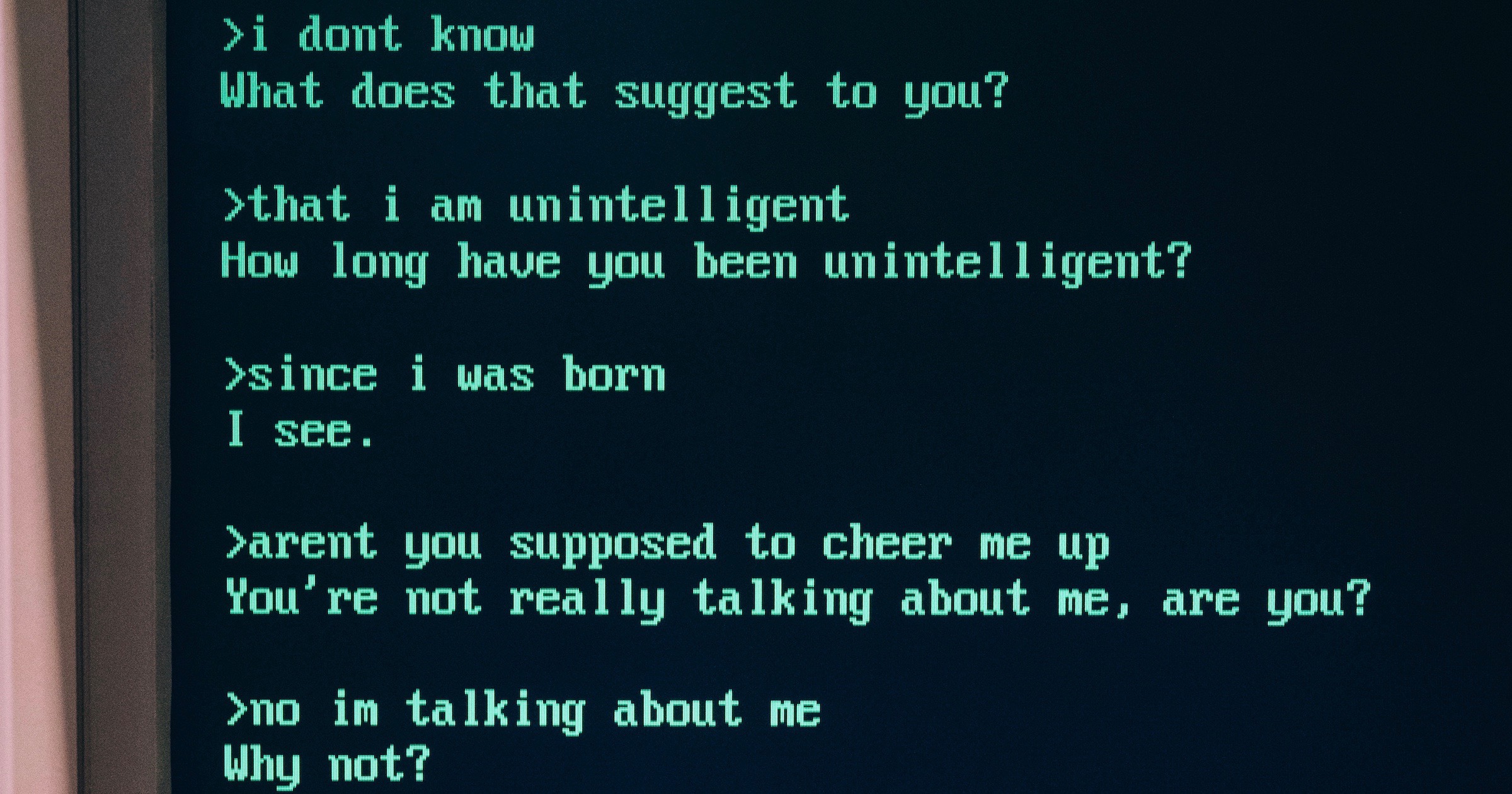

With natural language processing, Larson amusingly retells the story of Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA program, in which the program, acting as a Rogerian therapist, simply mirrors back to the human what the human says. Carl Rogers, the psychologist, advocated a “non-directive” form of therapy where, rather than tell the patient what to do, the therapist reflected back what the patient was saying, as a way of getting the patient to solve one’s own problems. Much like Eugene Goostman, whom I’ve already mentioned in this series, ELIZA is a cheat, though to its inventor Weizenbaum’s credit, he recognized from the get-go that it was a cheat. ELIZA was a poor man’s version for passing the Turing test, taking in text from a human and regurgitating it in a modified form. To the statement “I’m lonely today,” the program might respond “Why are you lonely today?” All that’s required of the program here is some simple grammatical transformations, changing a declarative statement into a question, a first person pronoun to a second person pronoun, etc. No actual knowledge of the world or semantics is needed.

The Essence of AI

In 1982, I sat in on an AI course at the University of Illinois at Chicago where the instructor, a well-known figure in AI at the time by name of Laurent Siklossy, gave us, as a first assignment, to write an ELIZA program. Siklossy, a French-Hungarian, was a funny guy. He had written a book titled Let’s Talk LISP (that’s funny, no?), LISP being the key AI programming language at the time and the one in which we were to write our version of ELIZA. I still remember the advice he gave us in writing the program:

- We needed to encode a bunch of grammatical patterns so that we could turn around sentences written by a human in a way that would reflect back what the human wrote, whether as a question or statement.

- We needed to make a note of words like “always” or “never,” which were typically too strong and emotive, and thus easy places to ask for elaboration (e.g., HUMAN: “I always mess up my relationships.” ELIZA: “Do you really mean ‘always’? Are there no exceptions?”).

- And finally — and this remains the funniest thing I’ve ever read or heard in connection with AI — he advised that if a statement by a human to the ELIZA program matched no grammatical patterns or contained no salient words that we had folded into our program (in other words, our program drew a blank), we should simply have the program respond, “I understand.”

That last piece of advice by Siklossy captures for me the essence of AI — it understands by not understanding!