Evolution

Evolution

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

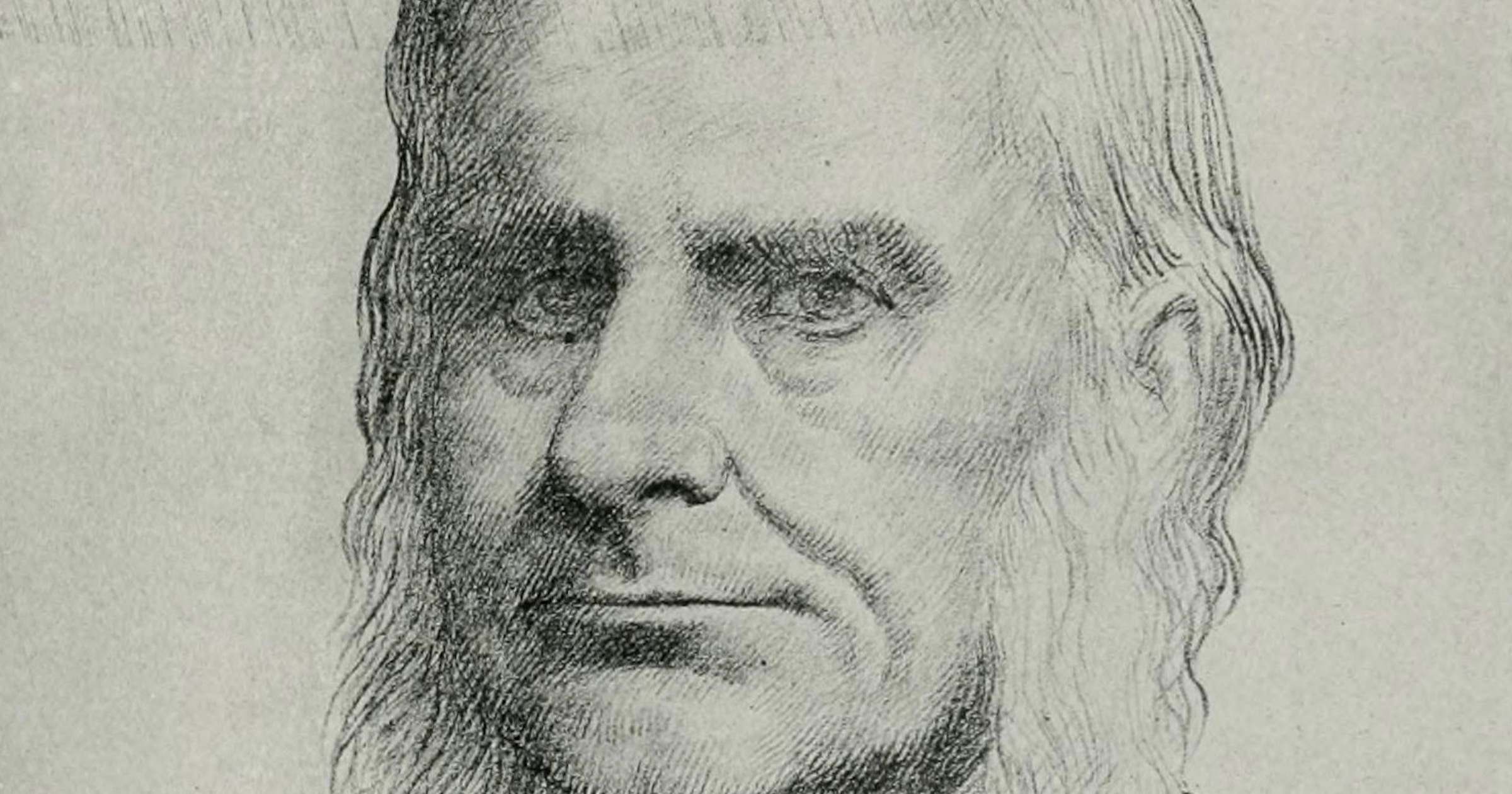

Sunday with the Devil’s Acolyte — Thomas Henry Huxley

In a recent post I made reference to Darwin as the “Devil’s chaplain” and now I’d like to add that this “chaplain” had an acolyte — Thomas Henry Huxley. Although the designation of Huxley as Darwin’s “bulldog” is well known, acolyte is a more appropriate term and here’s why. While Huxley’s public ferocity certainly earned him this popular canine coinage, it is less widely known that he led a Sunday “sermon” series. On January 7, 1866, Huxley kicked off the series with his lecture at St. Martin’s Hall, “On the Advisableness of Improving Natural Knowledge” (freely available in the published version of his collected essays here). Carefully reading this essay is important and revealing.

Historian Ruth Barton, who especially recognizes its importance and discusses it in her fascinating book The X Men, gives an account of Huxley’s involvement in the Sunday “lay sermon” series worth examining. Calling it a “masterpiece of rhetorical cunning,” Barton shows this essay to be one of Huxley’s most important in conveying his eloquent style and his passionate vision of the world, a world that he and most of his X Club comrades sought to create. The lecture opened to a packed house of two thousand with another two thousand being turned away.

Ten Main Points

The lecture may be summarized in ten main points as follows:

- Using Daniel Defoe’s classic account of the Great Plague of London in 1665 (A Journal of the Plague Year), Huxley chides that generation for submitting to the pandemic with “humility and penitence” regarding it as solely “the judgment of God” rather a matter of earthly “facts.”

- At the same time, Londoners looked for the culprits responsible for the city-wide fire that soon followed. It was wrong of that generation to so falsely divide the acts of God from the acts of man. They were responsible for both.

- Science could have solved both problems. There is “no reason to believe that it is improvement of our faith, nor that of our morals, which keeps the plague from our city; but, again, that it is the improvement of our natural knowledge. We have learned that pestilences will only take up their abode among those who have prepared unswept and ungarnished residences for them.” In other words, simple sanitation would have solved the problem of the plague.

- It is “natural knowledge” that serves as the “mother of mankind.”

- Natural knowledge even has the power “to lay the foundations of a new morality.”

- Since the universe is guided only by “matter and force, operating according to rigid rules,” and the earth is a mere “eccentric speck” of the cosmos, we should cast aside all authority built upon “books and traditions and fine-spun ecclesiastical cobwebs.”

- Humankind as part of this blind law-bound universe is not a special creation “but one of innumerable forms of life now existing on the globe,” to be regarded merely as “the last of an innumerable series of predecessors.”

- Those who would improve natural knowledge refuse “to acknowledge authority” and treat skepticism as “the highest of duties” with “blind faith the one unpardonable sin.”

- Truth can be found not in faith but only in scientific verification, which will bring about a new “ethical spirit” that will “constitute the real and permanent significance of natural knowledge.”

- We can rely on this because “there is but one kind of knowledge and but one method of acquiring it.” Natural knowledge — scientific knowledge — would build the world Huxley presented to his captivated audience that evening.

Good Old Sanitation

We can reveal the many problems with Huxley’s scientistic dystopia by working through it point-by-point. Huxley wants to present us with “the facts” and he does so by suggesting that good old sanitation rather than faith in God would have alleviated the plague. Although Huxley couldn’t have known this in 1866, plague is not primarily a sanitary problem; it is caused by Yersinia pestis, a gram-negative bacterium discovered in 1894 that infests fleas residing on rats. Thus the plague has a complex rat-flea-human vector relationship. Less than one hundred years after Huxley’s self-assured pronouncements on the plague, historian Charles F. Mullett pointed out that claiming the plague was a matter of sanitation and overcrowding is too simplistic, “to be unwashed and promiscuous did not in themselves cause the plague” (300). Stephen Porter’s The Great Plague goes further. He argues that cleanliness “is unlikely to have been a major factor in the absence of the plague in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries” (171). More likely is that some type of herd immunity to the Y. pestis bacteria was acquired by rats and/or people.

We can forgive Huxley for not knowing this, but can we forgive him for his adamant portrayal of scientific “facts”? Today we know his discussion of the plague is scientifically wrong. But Huxley should have been better acquainted with his history. Had he actually read Defoe instead of just citing him, he would have known that all kinds of naturalistic causes were given for the plague — comets, poor planetary alignments, earthquakes, weather, all took their respective places in the list of “causes” of this pestilential visitation. Huxley’s privileging of scientific facts is wrong; these facts are no better than the context in which they are formed. I do not doubt that prayerful contemplation — always a useful aid in adversity — would have been a better response to the plague than any of the naturalistic claims about it at the time. And Huxley’s claims notwithstanding, the plague would not have been averted much less removed with just a little more broom work.

The “Mother of Mankind”?

Having dispensed with Huxley’s points one through three, we might ask if “natural knowledge” (i.e. science) is truly the “mother of mankind” and even if so, how might it bring about this “new morality” of which Huxley speaks? Science has surely done wonderful things but it has also given us nuclear destruction, industrial illnesses, the morbidities of affluence (diabetes, coronary artery disease, asthma, lung cancer, etc.), and misguided horrors such as eugenics and racial hygiene (for more on this see John West’s Human Zoos). Fact is, science and the technologies that spring from them are at best neutral, as willing to kill and destroy as to preserve and protect. It is hard to understand how such neutral technical proficiencies in biology, anthropology, physics, mathematics, or anything else are likely to bring us to a new and better morality; they may even give us the tools with which to dig a deeper moral and ethical pit to fall into.

Huxley’s points six and seven are again examples of poor science leading to false metaphysical conclusions. The allusion to the insignificance of the earth — the so-called Copernican Principle — is easily turned on its head with the amazing fine-tuning of the universe. And as for this world being governed solely by law-like “matter and force,” Werner Heisenberg, one of the 20th century’s greatest scientists, didn’t think so. Were the materialist/atomists such as Democritus or the more immaterial/idealists such as Plato right? Heisenberg sided with the latter:

I think that modern physics has definitely decided in favor of Plato. In fact these smallest units of matter are not physical objects in the ordinary sense; they are forms, ideas which can be expressed unambiguously only in mathematical language.

Indeed, far from rejecting religious or metaphysical knowledge, Heisenberg rejected Huxley’s reductionism and insisted that the quest for the “one” — the final source of all understanding — cannot be given over to a single epistemic realm. For him, “the internal equilibrium of society depends . . . on the common relation to the ‘one’. Therefore the search for the ‘one’ can scarcely be forgotten” (Natural Law and the Structure of Matter, 32-33, 39). Huxley’s demand for scientific “facts” seems questionable in light of the new physics. Again, Heisenberg points out and asks rhetorically,

Even the demand for objectivity, which for a long time was considered a prerequisite for all science, has been limited in atomic physics by the fact that it is no longer possible to separate a phenomenon to be observed completely from its observer. Where is our contradiction between scientific and religious truth?

“Scientific and Religious Truth”, 472

Humanity and Common Descent

The contradiction is found neither in science or religion but only in a purposeless humanity given over to meaningless common descent. What possible moral or ethical foundation could arise from such a scientific “fact”?

Finally, Huxley seems to honor skepticism and damn authority only to succumb to the most naïve assumptions concerning science, and to find “the unpardonable sin of blind faith” in everyone but himself. The last point might be answered by seeing Huxley as the pathetic figure he finally became. Jacques Barzun observed that for all of this acolyte’s “pugnacity and evangelical passion to overstate his conclusions,” his scientism premised upon hard verification “left him naked before moral adversity. Europe became more and more like the vaunted jungle of the evolutionary books, and Huxley died heavyhearted with forebodings of the kind of future he had helped to prepare” (Darwin, Marx, Wagner, 63-64). So much for Huxley’s new “ethical spirit.”

Ruth Barton claims to “like and admire” Huxley, which is certainly her prerogative, but I can’t imagine why. He was always presumptuous, opinionated, and arrogant at least in his public persona. The Pauline fervor with which he delivered scientism’s sermon on the mount at St. Martin’s Hall might at least have been a model of conviction and public speaking if he hadn’t at the same time been so obviously wrong. And as if all that were not disconcerting enough, the very next essay in that collection, “Emancipation — Black and White,” published on May 20, 1865, in recognition of the American Civil War’s end, shows Huxley’s blatant racism (read on if you have the stomach for it). This shouldn’t surprise us; it did after all come from the Devil’s acolyte.