Bioethics

Bioethics

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

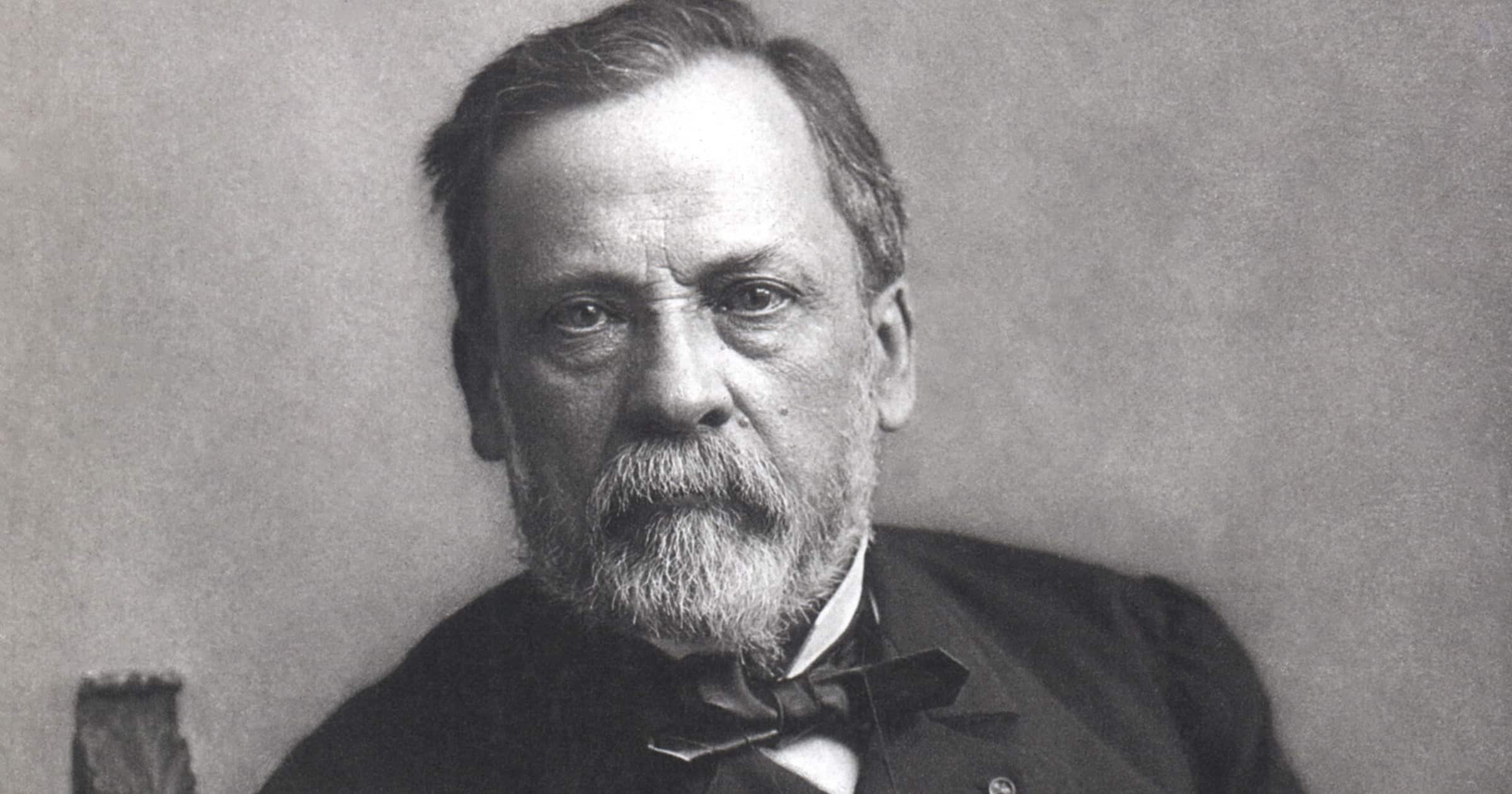

Louis Pasteur, in Memoriam

Today is the 200th anniversary of the French scientist Louis Pasteur’s birth. So what, you might say? Why does he matter?

It turns out he mattered a great deal. He made fundamental scientific discoveries and also kept important French industries from failing.

Pasteur began the field of stereochemistry. He demonstrated that organic molecules could come in mirror-image forms. He also discovered the basis of fermentation and found a way to prevent the spoilage of wines and beer. He identified two diseases of silkworms and developed methods to separate sick from healthy silkworms, thus saving the French silk industry.

Pasteur demonstrated the bacterial basis of many diseases and helped identify the organisms responsible. He helped to develop infection control by introducing antiseptic practices. Other important contributors were the German scientist Robert Koch and the English physician Edward Lister.

He developed the first vaccine for anthrax, and the viral disease rabies. This one achievement won him awards around the world.

Disproving Spontaneous Generation

Perhaps Pasteur is most famous for disproving spontaneous generation. He demonstrated that germs on dust were responsible for spoilage and microbe growth, by sterilizing broth in swan-necked flasks and then letting the broth sit. The swan necks prevented dust and microbes from getting in, so nothing grew. Spontaneous generation did not take place. (Do you suppose if he had waited 500 million years, it might have happened?)

Now, from what sort of background did this prodigy emerge?

Pasteur was born December 27, 1822, in Dole, France, to a poor family. His father was a tanner. They valued education and found support to send him to the best schools they could afford. Pasteur loved painting and drawing and neglected his studies for years. When it dawned on him that art was not likely to earn a living for him, he switched to chemistry.

He was not a brilliant student, but he worked very hard once he put his mind to it. It took him three tries to pass the exam he needed to get into his desired school. In later years, he attributed his success to his tenacity. He was also good at finding mentors. He impressed senior scientists with his hard work and fearlessness in tackling some of the most difficult scientific problems of the day.

Pasteur’s early research was entirely self-funded. His wife, Marie, actively supported his work and acted as his amanuensis in the lab. Together they had five children, three of whom died.

The Pasteur Institute

As he achieved fame, he was able to take research positions at more and more prestigious institutions. Finally, he was able to found the Pasteur Institute, which is dedicated to the discovery and prevention of the causes of disease, particularly rabies.

He was fond of grand public demonstrations that were not without risk, but he was always lucky. He was given access to an abandoned estate by Emperor Napoleon III in order to revive its silk industry and was able to make it enormously profitable within a year using what he had learned about silkworm diseases.

He demonstrated that his anthrax vaccine worked by dividing a herd of sheep in two and vaccinating one-half. He then let the whole herd graze on anthrax-infected pasture; the vaccinated sheep survived, and the rest died.

Most famously, he used a rabies vaccine (reports differ as to how successful it had been on animals) to treat a boy who had been mauled by a rabid dog. The boy had not yet developed symptoms. Pasteur decided to take a risk and gave him his vaccine in an attempt to prevent the development of the disease. He administered his vaccine at increasing strength over multiple days. The boy survived and made Pasteur famous around the world. Once again, he was lucky. The boy did not die of rabies and the treatment did not kill him either. A similar regimen of shots is still used today, though it has been considerably refined and tested.

Pasteur was and is the target of accusations that he stole ideas from other people and misrepresented some of his methods. Clearly, Pasteur was a hard-working scientist with considerable acumen, who greatly advanced the science of his day. He was highly respected and won just about every award available. But he also sometimes borrowed ideas without giving credit and did not fully report his methods. For example, he used a veterinarian’s method to prepare the rabies vaccine he used on the boy, not his own method, and never gave the veterinarian credit.

Some True Accusations

Pasteur told his family on no account to give his lab notebooks to anyone after his death. They obeyed his wishes until his last descendant handed them over to the Pasteur Institute in the late 1960s. The notebooks revealed that at least some of the accusations were true.

In 1868 Pasteur had a stroke which left him paralyzed on one side, but he continued to work, writing papers and carrying on scientific disputes with his competitors, all with the aid of his lab assistants, some of whom were famous scientists in their own right. Finally, more strokes and uremia took his life on September 27, 1896. He must have been a kind man because he was greatly loved. His last weeks were filled with visits from family, friends, scientists, and co-workers. His students took turns sitting with him.

I suspect Pasteur knew that some of what he had done was wrong and he did not want to be exposed. But as one of his contemporaries put it, he was a practical Catholic. He received the last rites and died clutching a crucifix, which to me indicates he was pleading for mercy from God.

He represents the best and worst traits of scientists — incredible discoveries, great insight and productivity, the insistence on experimental testing and verification, and the desire for glory, for success at just about any cost.

“Life Comes Only from Life”

Pasteur wrote in French and little of his work has been translated. But there are quotes attributed to him in English that are likely true, from what I have read. Reading them takes me back to the mind and heart of a great scientist, however flawed he was.

- “Great problems are now being handled, keeping every thinking man in suspense; the unity or multiplicity of human races; the creation of man 1,000 years or 1,000 centuries ago; the fixity of species, or the slow and progressive transformation of one species into another; the eternity of matter; the idea of a God unnecessary: such are some of the questions that humanity discusses nowadays.”

- “The greatest derangement of the mind is to believe in something because one wishes it to be so.”

- “No, there is now no circumstance known in which it can be affirmed that microscopic beings came into the world without germs, without parents similar to themselves. Those who affirm it have been duped by illusions, by ill-conducted experiments, spoilt by errors that they either did not perceive or did not know how to avoid.”

- “Life comes only from life.”

- “One must not assume that an understanding of science is present in those who borrow the language.”

- “Little science takes you away from God but more of it takes you to Him.”

- “There is a time in every man’s life when he looks to his God, when he looks at his life, when he wonders how he will be remembered.”

Amen.

Notes

- Berche, Patrick. “Louis Pasteur, from crystals of life to vaccination.” Clinical microbiology and infection 18 (2012): 1-6.

- Cavaillon, Jean-Marc, and Sandra Legout. 2022. “Louis Pasteur: Between Myth and Reality” Biomolecules 12, no. 4: 596. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12040596

- Kendall A. Smith. “Louis Pasteur, the Father of Immunology?” Frontiers in Immunology 2012; 3: 68.