Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Neuroscience & Mind

Neuroscience & Mind

Blind Ambition — Revisiting Searle’s Chinese Room

Editor’s note: We are delighted to welcome Science After Babel, the latest book from mathematician and philosopher David Berlinski. This article is adapted from Chapter 18.

I believe. I want. I do. What could be simpler? Intelligence is the overflow of the mind in action. In dreaming or desiring, on the other hand, I occupy a world bounded entirely by memory, meaning, and belief: I need do nothing. That overflow is entirely internal. In either case, our intelligence is directed toward specific objects or states of affairs. I believe — what? That Clearasil Starves Pimples or that Pepsi Is the Choice of a New Generation; I desire — what? That the young Sophia Loren might step smoldering from the television set for perhaps an hour or that I might win a MacArthur Fellowship (the academic equivalent of the Irish Sweepstakes). What I believe (or desire) and what is believed (or desired) are connected by something very much like an intentional arrow, a kind of miraculous metaphysical instrument. The relationship between my thoughts and their objects is thus strange from the first. But this relationship between what I think and what I think about is duplicated in language itself: like the thoughts that they express, the sentences of a natural language transcend themselves in meaning.

From the Inside Out

In seeing things from a first-person stance, with the entire world revolving around my own ego — a kind of Ptolemaic system in psychology — I direct the arrow of intentionality from the inside out, infusing the objects and properties of the external world with all of the significance that they ever possess. I assume, of course, that others do as much. Read forward, the arrow of intentionality goes from what I feel to what I do; read backward, from what is done to what is felt. The sense that we are all in this together arises only as the result of a supremely imaginative kind of back-pedaling; the interpenetration of two human souls, when it occurs, is wordless.

There is more. Each of us acts in the world as both subject and object: we do, and things are done to us. In moving away from the lunatic solipsism in which my ego exists in the absence of all others, I endow those human beings in my own perceptual ken with more or less the same cognitive states that I myself enjoy. This is the basis for a sense of sympathy. The endowment itself, I presume, may be reversed, as when I myself figure in someone else’s awareness as an imaginatively constructed subject of experience. But here is a queer, artful point. The inferences that I make about others, others make about me. My inferences about others I cannot verify, but their inferences about me represent something like the backward wash of a familiar wave. A subject acting simultaneously as a psychological object enjoys a unique Archimedean perspective on the system of inferences by which mental life in the large is constructed.

A Very Deft Argumentative Maneuver

This confluence of circumstance suggested to the American philosopher John Searle a very deft argumentative maneuver, something akin, really, to a movement in judo. His arguments were prompted by work undertaken at Yale by the psychologist Roger Schank. Like many other American theorists, Schank has approached the problem of artificial intelligence with a kind of bluff, no-nonsense sense that getting a machine to understand something is a matter of attending to the details in a patient, straightforward way. In a photograph at the back of his book, The Cognitive Computer, he stands with his arms folded over his ample belly, scowling directly into the camera, an expression of earnest ferocity on his face, as if to suggest that by the time he got through with them, those computers of his would either shape up or ship out. His aim, as he explains things, is to teach the digital computer to comprehend simple stories of the sort that might be told to children.

The exercise is set out without irony. The education of the digital computer in this regard commences with what Schank calls a script — a kind of running, rambling background account in which the saliencies of various stories are set out and explained. With the scripts in hand, the computers are prepared to make sense of what they read. They are then interrogated with a fine eye directed toward telling whether they have understood what they have absorbed. In fact, Schank’s machines do get quite a bit right; the record of their conversation is admirable, and the unbiased reader often has the feeling that just possibly he is reading something strange and remarkable.

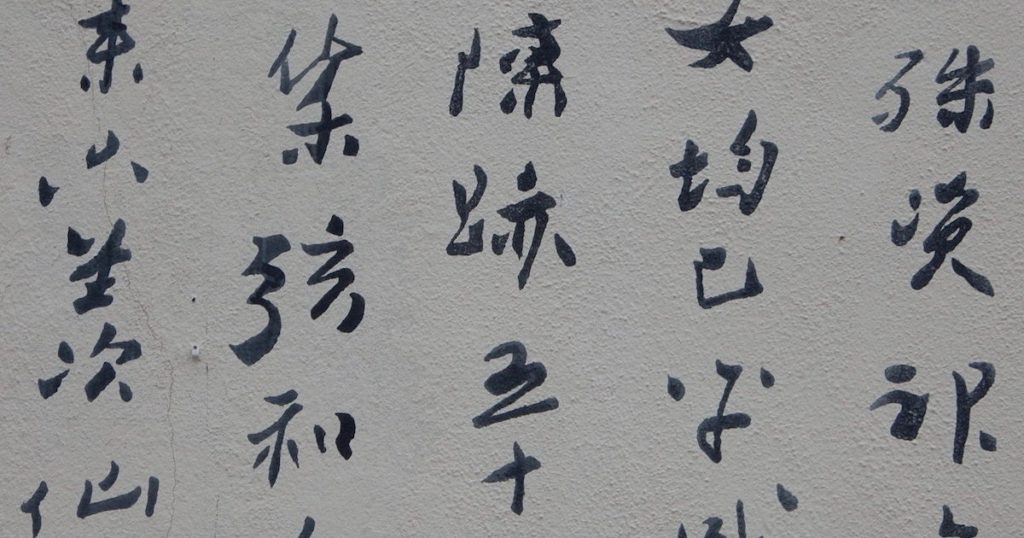

It is against this conclusion that Searle has set his face. It is a simple fact, Searle begins, that he is utterly ignorant of the Chinese language. Suppose that he were to be locked in a room with a large sample of Chinese script — the samples, say, arranged on cardboard sheets. Now imagine that Searle were to be given “a second batch of Chinese script together with a set of rules for correlating the first batch with the second.” The rules are in English. A third collection of scripts is presented Searle. And another set of rules. This makes for three separate sets of Chinese symbols and two sets of English rules.

From Searle’s point of view, the material he confronts is an incomprehensible jumble. From the outside, where sense is made of all this, those Chinese symbols have a specific meaning. The first corresponds to a general script — the sort of thing that a computer would need in Schank’s setup to make sense of a story. The second is actually a story in Chinese. The third represents a list of Chinese questions. From time to time, those questions are presented to Searle with a nudge and a wink and a tacit request that he say something. In answering, Searle consults his set of rules. The two sets enable Searle to match the questions to the story by means of the background script. In this respect, Searle remarks, he is precisely in the position of the digital computer.

How Searle Sees

But (a very excited, explosive but!) under such circumstances would there be any inclination to say that a subject so situated understands the meaning of the symbols he is manipulating? An observer might come to this conclusion. Put a question in Chinese to this character, after all, and he answers in Chinese. Yet this is not at all how Searle himself sees things. Whatever he may be able to say in Chinese, he remains confident that he understands nothing of what he has said and is prepared to champion his ignorance defiantly. Some great notable aspect of what it means to understand a language has simply been overlooked.

For the most part, computer scientists have tended to ignore Searle’s argument and the point of view that it represents. It had long been known in science that you cannot beat something (a research grant) with nothing (a destructive argument), and what Searle had to offer them was nothing at all. Analytic philosophers responded promptly to Searle. The results are confusing. A great many superbly confident rebuttals appear to contradict one another. As for myself? When pressed on the point, I tend to run my hands through my hair or tug mournfully at my ears, gestures I am convinced that suggest that I have something tack-sharp to say were I willing only to say it.