Physics, Earth & Space

Physics, Earth & Space

“Simulation Hypothesis” and Star Trek — Intelligent Design by Another Name

The “simulation hypothesis” is getting a lot of attention these days in the mainstream media. What’s the simulation hypothesis? According to a recent explanation by theoretical physicist Sabine Hossfelder, it holds that the universe is much like the Matrix, “coded by an intelligent being”:

According to the simulation hypothesis, everything we experience was coded by an intelligent being, and we are part of that computer code. That we live in some kind of computation in and by itself is not unscientific. For all we currently know, the laws of nature are mathematical, so you could say the universe is really just computing those laws. You may find this terminology a little weird, and I would agree, but it’s not controversial. The controversial bit about the simulation hypothesis is that it assumes there is another level of reality where someone or some thing controls what we believe are the laws of nature, or even interferes with those laws.

The belief in an omniscient being that can interfere with the laws of nature, but for some reason remains hidden from us, is a common element of monotheistic religions. But those who believe in the simulation hypothesis argue they arrived at their belief by reason. The philosopher Nick Bostrom, for example, claims it’s likely that we live in a computer simulation based on an argument that, in a nutshell, goes like this. If there are a) many civilizations, and these civilizations b) build computers that run simulations of conscious beings, then c) there are many more simulated conscious beings than real ones, so you are likely to live in a simulation.

David Klinghoffer has explained what ought to be clear: the “simulation hypothesis” entails “that our universe is intelligently designed. That’s what a computer simulation is, obviously, intelligent design.”

Science and Religion?

Hossfelder’s recent post goes on to explain why she rejects the “simulation hypothesis,” giving less-than-compelling reasons such as that “mixing science with religion … is generally a bad idea,” as is employing arguments from ignorance. Since “nobody presently knows how to reproduce General Relativity and the Standard Model of particle physics from a computer algorithm running on some sort of machine,” she maintains we don’t know how “to reproduce all our observations using not the natural laws that physicists have confirmed to extremely high precision, but using a different, underlying algorithm, which the programmer is running.” Arguments like these amount to (my paraphrase) “This isn’t possible because we don’t yet know how to do it.” Such arguments usually don’t get you very far. Presumably “simulation hypothesis” advocates would retort that highly advanced civilizations would be able to figure out how to run the necessary calculations.

Design by Another Name

None of these problems with her critiques mean the simulation hypothesis is correct (Michael Egnor has his own potent critique from an ID-friendly viewpoint). Thus, the universe may be intelligently designed and yet not be a simulation. The theory of intelligent design does not rise or fall with the simulation hypothesis, but it’s an interesting idea to think about — at the very least it’s one possible intelligent design model that can be debated.

The main point here is that the “simulation hypothesis” shows that the possibility that the universe was intelligently designed is increasingly a serious topic of conversation among scientists and other respected thinkers. A recent article by Jack Butler at National Review covers a new documentary, A Glitch in the Matrix, which provides a “fair and evenhanded” treatment of the simulation hypothesis. Hossfelder observes two noteworthy names who find merit in the idea:

Elon Musk is among those who have bought into it. He too has said “it’s most likely we’re in a simulation.” And even Neil deGrasse Tyson gave the simulation hypothesis “better than 50-50 odds” of being correct.

Another Well-Known Thinker

Incidentally, there’s another highly respected thinker who takes the simulation hypothesis—and design of the universe—seriously. It’s Mr. Spock from Star Trek.

In 2018, between seasons one and two of the latest Star Trek series, Discovery, the franchise put out “Short Treks.” These are 15-minute episodes that delve deeper into character and plot development. They’re for the nerds for sure, but they’re fun.

Between seasons two and three of Discovery, in late 2019, a “Short Trek” was released that was titled Q & A. It features a young Mr. Spock (played by Ethan Peck). In the short, Spock is experiencing his first day aboard the USS Enterprise as science officer. After being instructed by his superior officer (Number One played by Rebecca Romijn) to “barrage every crewman you meet with questions, starting with me, to the point you become an annoyance,” Spock starts firing away. The two then proceed to get stuck in a turbolift (the fancy Star Trek version of an elevator), and Spock continues to push the questions. Eventually he asks:

Have you considered the possibility that the ubiquity of mathematical constants in nature such as e or the so-called Golden Ratio imply that the universe was designed or perhaps is an enormous simulation?

Here, the young Mr. Spock has just alluded to a classic argument for the design of the universe based upon its mathematical order and rationality. This is similar to what Nobel Prize-winning physicist Eugene Wigner called the “unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics.” Here’s how Wigner put it in his 1960 paper, “The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences”:

The world around us is of baffling complexity and the most obvious fact about it is that we cannot predict the future. Although the joke attributes only to the optimist the view that the future is uncertain, the optimist is right in this case: the future is unpredictable. It is, as Schrodinger has remarked, a miracle that in spite of the baffling complexity of the world, certain regularities in the events could be discovered….

It is difficult to avoid the impression that a miracle confronts us here, quite comparable in its striking nature to the miracle that the human mind can string a thousand arguments together without getting itself into contradictions, or to the two miracles of the existence of laws of nature and of the human mind’s capacity to divine them….

The miracle of the appropriateness of the language of mathematics for the formulation of the laws of physics is a wonderful gift which we neither understand nor deserve. We should be grateful for it and hope that it will remain valid in future research and that it will extend, for better or for worse, to our pleasure, even though perhaps also to our bafflement, to wide branches of learning.

This is an argument that apparently appeals to the young Mr. Spock, who directly suggests that perhaps “the universe was designed.” He certainly shows no evidence of opposing it. Instead, he shows evidence of openness, and that he thinks the argument is worth taking seriously.

Intelligent Design as an Annoyance?

Spock then immediately asks, “Am I becoming an annoyance?” I slightly suspect that was a self-aware moment for the show, because the writers realize that many fans would find it annoying — if not blasphemous — that Star Trek’s hallowed science officer would be open to intelligent design.

For my part, although I’ve never been to a Star Trek convention, I’m a part time Star Trek fan — rewatching many old episodes in order to pass long nights of lab research during my PhD work. Thus, I’m well-aware that a lot of Star Trek fans style themselves as highly rational atheists. Many of those folks would probably be aghast to learn that Mr. Spock doesn’t necessarily oppose intelligent design. Better to call his openness to the idea an “annoyance”? Perhaps.

Another Fact for Your Consideration

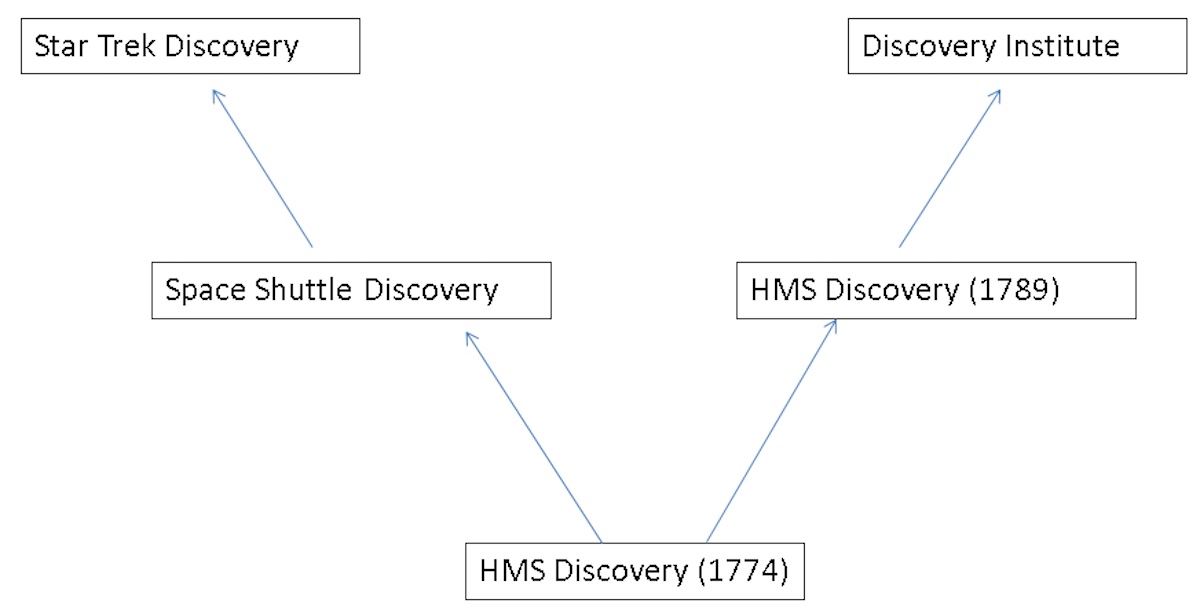

I’m not trying to annoy anyone, but here’s another fact that some Star Trek fans might not like: Discovery Institute, the world’s institutional home for intelligent design, and the latest show Star Trek series Discovery share a common ancestry in their namesake. Here’s the phylogeny:

Here’s my point: Whether the simulation hypothesis is, as Jack Butler puts it, a reflection of a “sad delusion behind the ersatz combination of logic games, pop-culture references, and personal idiosyncrasies that make up this would-be pseudo-religion,” or whether it’s “pseudoscience” as Sabine Hossfelder puts it, or whether it’s correct, one thing is clear: the hypothesis is forcing thinkers to take seriously the special mathematical properties of the universe which seem to indicate that it was designed.