Evolution

Evolution

Paleontology

Paleontology

Fossil Friday: New Evidence Against Dinosaur Ancestry of Birds

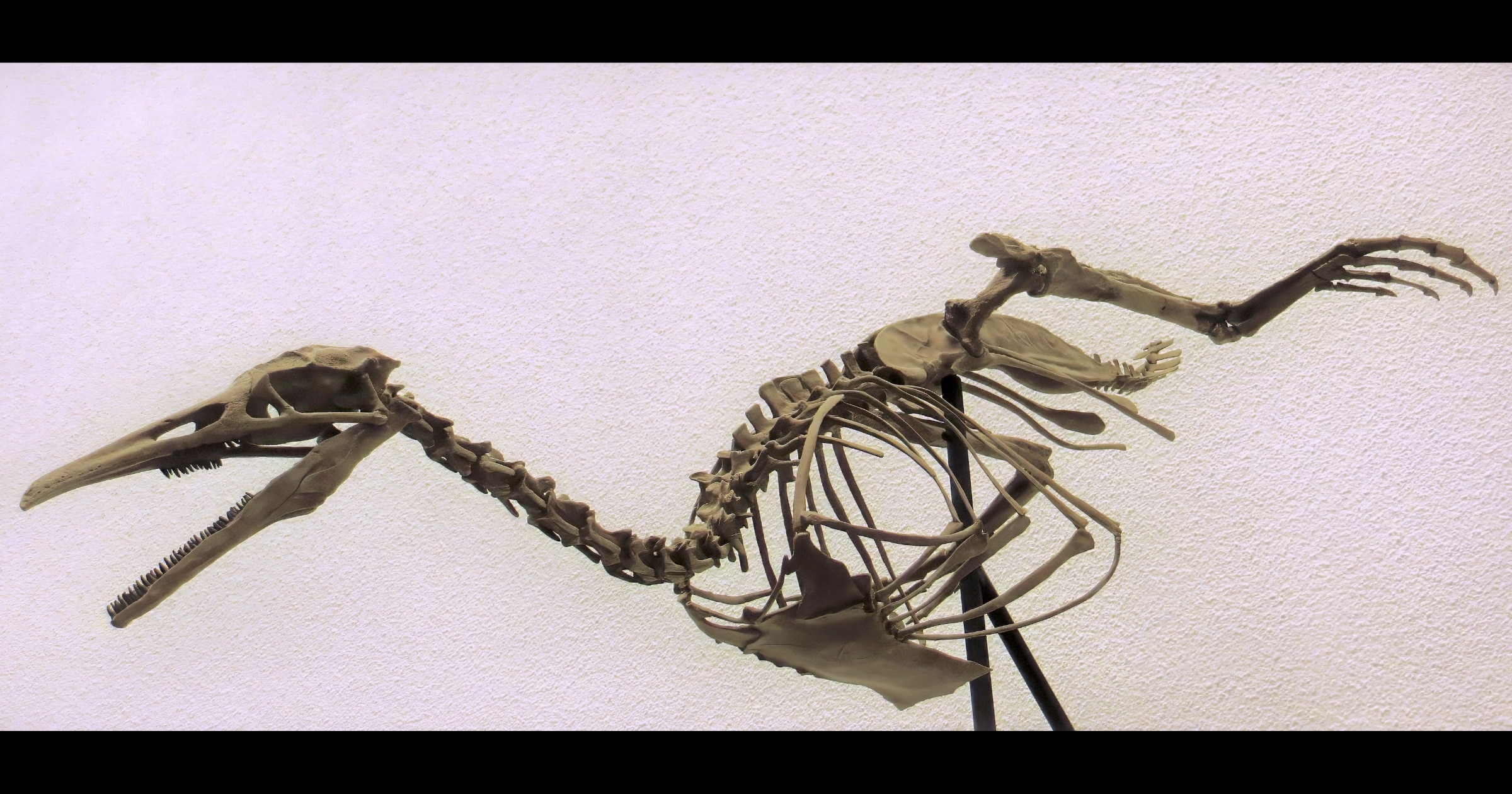

This Fossil Friday we revisit the ancestry of birds, with the featured skeleton of the Late Cretaceous bird Hesperornis gracilis, exhibited at the Natural History Museum in Karlsruhe, Germany. Hesperornis was a flightless and toothed marine bird, somewhat similar to modern penguins, and lived contemporaneous with some of the raptor dinosaurs that are well known from the Jurassic Park movies.

Few hypotheses in evolutionary biology have become as popular among lay people as the postulated ancestry of birds from bipedal dinosaurs. Indeed, many a school kid will tell you proudly that birds simply are surviving dinosaurs. The theropod ancestry of birds has become an evolutionary dogma that is almost universally accepted and taught as the consensus view. However, there are a few dissenters, among whom the paleornithologist Alan Feduccia from the University of North Carolina certainly is the most prominent. He famously coined the term “temporal paradox” for the fact that the fossil record of the assumed theropod stem group of birds tends to be younger than the oldest actual birds. Last week I discussed new evidence that makes this temporal paradox much worse (Bechly 2023).

Beyond the Fossil Record

However, Feduccia’s critique of the dinosaur-bird hypothesis is not based just on problems with the fossil record, but also on conflicting evidence from comparative anatomy. Now, he presents new evidence that still more sharply contradicts the consensus view. One of the arguments for a dinosaur-bird relationship has been the presence of a so-called “open” acetabulum, which “is a concave pelvic surface formed by the ilium, ischium, and pubis, which accommodates the head of the femur in tetrapods.” Feduccia (2024) studied the acetabulum in early basal birds and found that their acetabulum tends to be partially closed and an antitrochanter (process of the ischium or iliac) is absent. This casts strongly into doubt one of the key characters for a dinosaur-bird relationship and suggests that this hypothesis must be re-evaluated. The fact that microraptorids and troodontids “also exhibit partial closure of the acetabulum and lack an antitrochanter is a further incongruity in that these taxa should exhibit “typical” theropod pelvic girdle modifications for terrestrial cursoriality.” This could support the view of several experts (e.g., Martin 2004, and various studies cited by Feduccia), that these maniraptoran taxa represent secondarily flightless birds rather than theropod dinosaurs.

Feduccia concluded his new study with this remarkable statement:

The hypothesis that birds are maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs, despite the certitude with which it is proclaimed, continues to suffer from unaddressed difficulties … Until problems like those discussed here — and many others that continue to be dismissed either by appeal to “consensus” or through overconfidence in the results of phylogenetic analysis of morphological data — have satisfactorily been resolved, skepticism toward the current consensus and continued investigation of alternative hypotheses are needful for the promotion of critical discourse in vertebrate phylogenetics and evolutionary biology.

Birds and dinosaurs may not represent arbitrary chunks of an evolutionary grade after all, but may instead represent distinct natural kinds. At the very least, the evidence seems to be much more ambiguous, weaker, and less convincing than most evolutionary biologists love to pretend.

References

- Bechly G 2023. Fossil Friday: Fossil Bird Tracks Expand the Temporal Paradox. Evolution News December 29, 2023. https://evolutionnews.org/2023/12/fossil-friday-fossil-bird-tracks-expand-the-temporal-paradox/

- Feduccia A 2024. The Avian Acetabulum: Small Structure, but Rich with Illumination and Questions. Diversity 16: 20, 1–28.DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/d16010020

- Martin LD 2004. A basal archosaurian origin for birds. Acta Geologica Sinica 50(6), 978–990. https://caod.oriprobe.com/articles/7989071/A_basal_archosaurian_origin_for_birds.htm