Evolution

Evolution

Biologist Nathan Lents: Beauty in Error

At The Human Evolution Blog, biologist Nathan Lents has a new post up, “The Beauty of Imperfection: Why I Wrote ‘Human Errors’.” The reference is to his recent book, Human Errors: A Panorama of Our Glitches, from Pointless Bones to Broken Genes. He has a different take on imperfection, one more optimistic than one might expect from someone who writes about what’s wrong with us. He deserves credit for what he writes.

He first enumerates the flaws he finds in the human body, many of which have been discussed here already. It is not my intention to argue about flaws or points of disagreement. Instead I want to say a little about where I agree.

Is a Mutation an Error or an Opportunity?

Mutations are either the consequence of damage to the DNA or random copying errors during replication of the DNA. They are a natural process. We think of mutations as bad things. But they can be helpful. They sometimes cause disease but they also can ameliorate other diseases. Information from mutations can be used to unravel the intricacies of cell and molecular biology. They provide diversity so that no two of us are the same.

Lents would say they are what allows evolution to take place. He attributes more creative power to them than I do. Here is what he says:

But occasionally, very rarely in fact, a mutation comes along that gives new function, new meaning, to a gene. These extraordinary mutations are the raw material of all of the great diversity of the living world, of everything that moves and breathes and gives birth to new life.

The Most Unlikely of Creatures

Dr. Lents finds us to be more flawed than other animals, and he attributes those problems to our past. In the long past we lived in an environment rich in fruits and vegetables (until we didn’t), and so we lost the ability to make vitamin C, or vitamin B12, or folate, to name a few. We need to get all these things from the food we eat.

We also have very difficult reproduction. Babies’ heads are almost too large to pass through a woman’s pelvis. We have a fairly long gestational period, and infants need extensive care for a long period of time. Many mothers and infants used to die before the advent of modern medicine and many still do in the developing world. So why are we here with all these problems? Lents says:

Only a species with a social structure as tightly woven as ours could ever have survived with bodies this limited. If your eyesight is no good for hunting, perhaps you can be a homesteader. If you are too sickly for child rearing, maybe you can craft tools or clothing. If your body is too worn or crippled, your wisdom or cleverness is still of great value to your people. We descend from a long line of not just hunters and gathers, but shamans and seamstresses, nannies and tradesmen, artisans and bureaucrats. Our ancestors were dreamers and planners, and who would want it any other way?

Our social structure, with its rules and consequences, division of labor, sharing of tasks, and the care of others are all possible for at least four reasons:

- Language. This is foundational for everything.

- A theory of mind. We know that there are people besides ourselves, and we can, by observing their action, begin to understand what they are thinking and why.

- Empathy endows us with the desire to help those who need it.

- Living together as social beings, but with some independence and the capacity to learn and grow. This should be self-explanatory.

Note that these are things that humans do that exceed the capacity of the great apes.

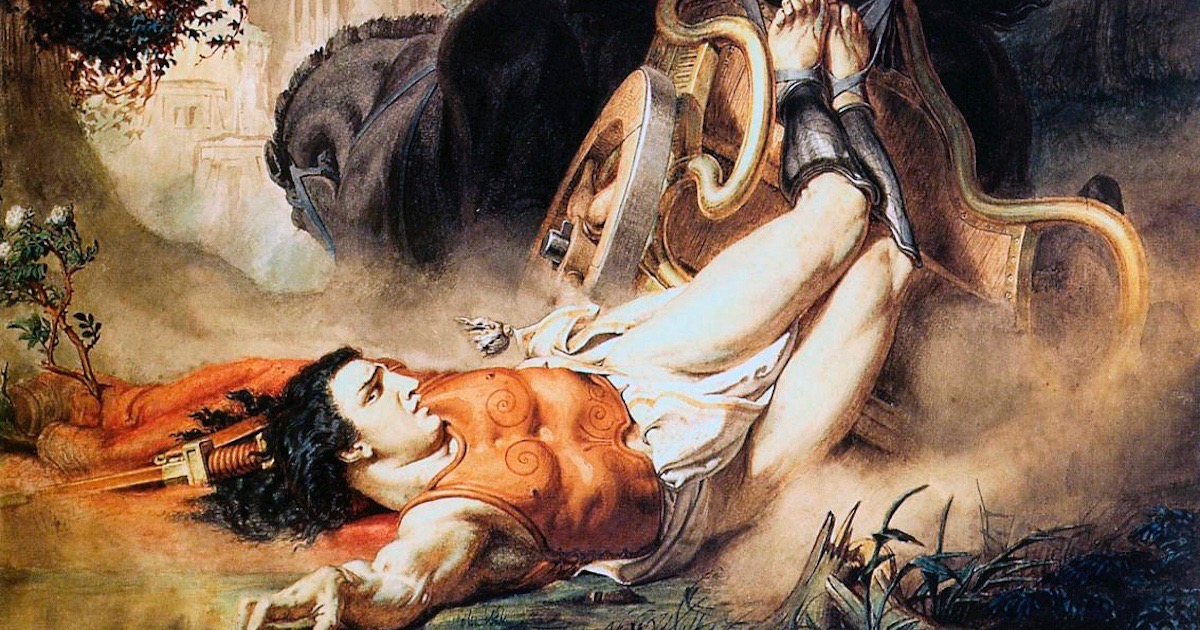

“Men Are Men, They Needs Must Err”

So says the nurse to Hippolytus, in Euripides’ play by the same name. It seems Lents agrees.

From talking about our physical flaws, he moves to the mistakes we make. But he takes it one step further. He credits both our inherited flaws and personal mistakes for making us who we are. He draws the moral lesson that:

All we must do to continue to thrive is to learn from our mistakes. But before we can learn from them, we must acknowledge them. Personally, I go further than that. I celebrate them.

I can agree with that. And then he closes with something I can heartily agree with.

Of all the species that have ever walked the earth, we may be the most flawed, but we are certainly the most beautiful.

Image: Hippolytus takes a fatal tumble from his chariot; by Lawrence Alma-Tadema [Public domain].