Physics, Earth & Space

Physics, Earth & Space

The Empty Heavens — Two Ways to Look at It

Adam Kirsch over the weekend had a thoughtful essay in the Wall Street Journal, meditating on the coming 50th anniversary of the first moon landing. His takeaway is a downer: From the inspiring medieval belief in the heavens as a “supernatural realm where souls go after death to dwell in the presence of God,” we humans have learned more about the cosmos and our place in it. We now know we have to settle for the reality of Earth spinning in overwhelmingly cold, empty, and hostile space. We’re alone, and it’s kind of terrifying.

From “Our Quest for Meaning in the Heavens”:

Astronomy doesn’t disprove religion, of course, but it does present problems for those who want to see an intelligible message in the cosmos. In the early 17th century, the English poet John Donne observed that humanity had lost its bearings in the universe: “The sun is lost, and the earth, and no man’s wit/Can well direct him where to look for it.” The heavens, once the setting for the Earth and human beings, had become space, a void in which we wander. Blaise Pascal, one of the greatest mathematicians and theologians of that era, famously wrote that “the eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.”

Isn’t it interesting how the same data, looked at a little differently, can give a dramatically changed perspective. Watch this from Bijan Nemati, an astrophysicist at University of Alabama-Huntsville. The video is bonus material from last week’s episode of Science Uprising, “Fine Tuning: You Don’t Suck!”

As Dr. Nemati observes, the Earth is indeed rare. And as science advances, it is looking rarer and rarer. Putting aside the seeming impossibility of evolving the first life without intelligent design, on Earth or anywhere else — the subject of this week’s Science Uprising episode — the conditions needed for an Earth-like planet are exceedingly tough to meet: “You’d have to look at tens of thousands of Milky Ways, at least, before you should expect to see a single Earth.” Nemati details some of the hurdles, as well as other conditions, far tougher, that must have been tuned just right at the Big Bang, with crazy precision, in order for stable planets and stars to form. The rarity of our “blue marble” suggests either near-impossible mind-blowing good luck, or, more in line with common-sense and our experience of reality, intelligent design.

Medieval religious believers were innocent of all this. Kirsch is right in saying that “Astronomy doesn’t disprove religion.” And he’s right that the modern picture of the heavens is different from the medieval or ancient one. But the “intelligible message in the cosmos” is more evident today, as a matter of objective science, than ever before. Pascal was frightened, as many of us would likely admit we are sometimes about such matters. But he didn’t know then what we know now.

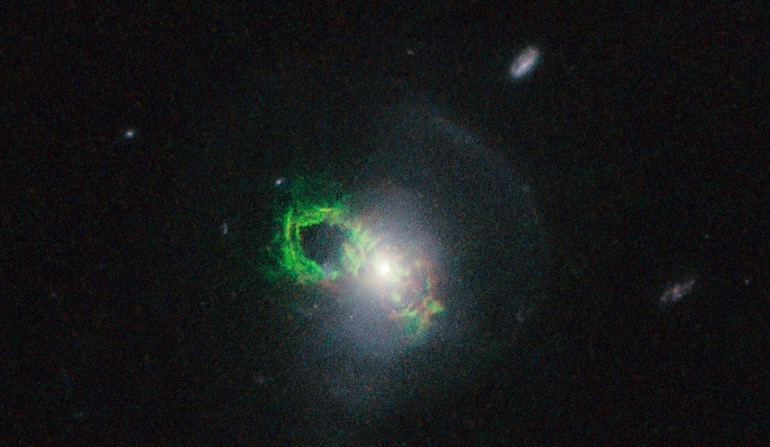

Photo: “Teacup Galaxy,” SDSS J1430+1339, by NASA, ESA, and William Keel [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.