Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Evolution

Evolution

News Media

News Media

Journalist Finds a “Cover-Up” by the Bronx Zoo

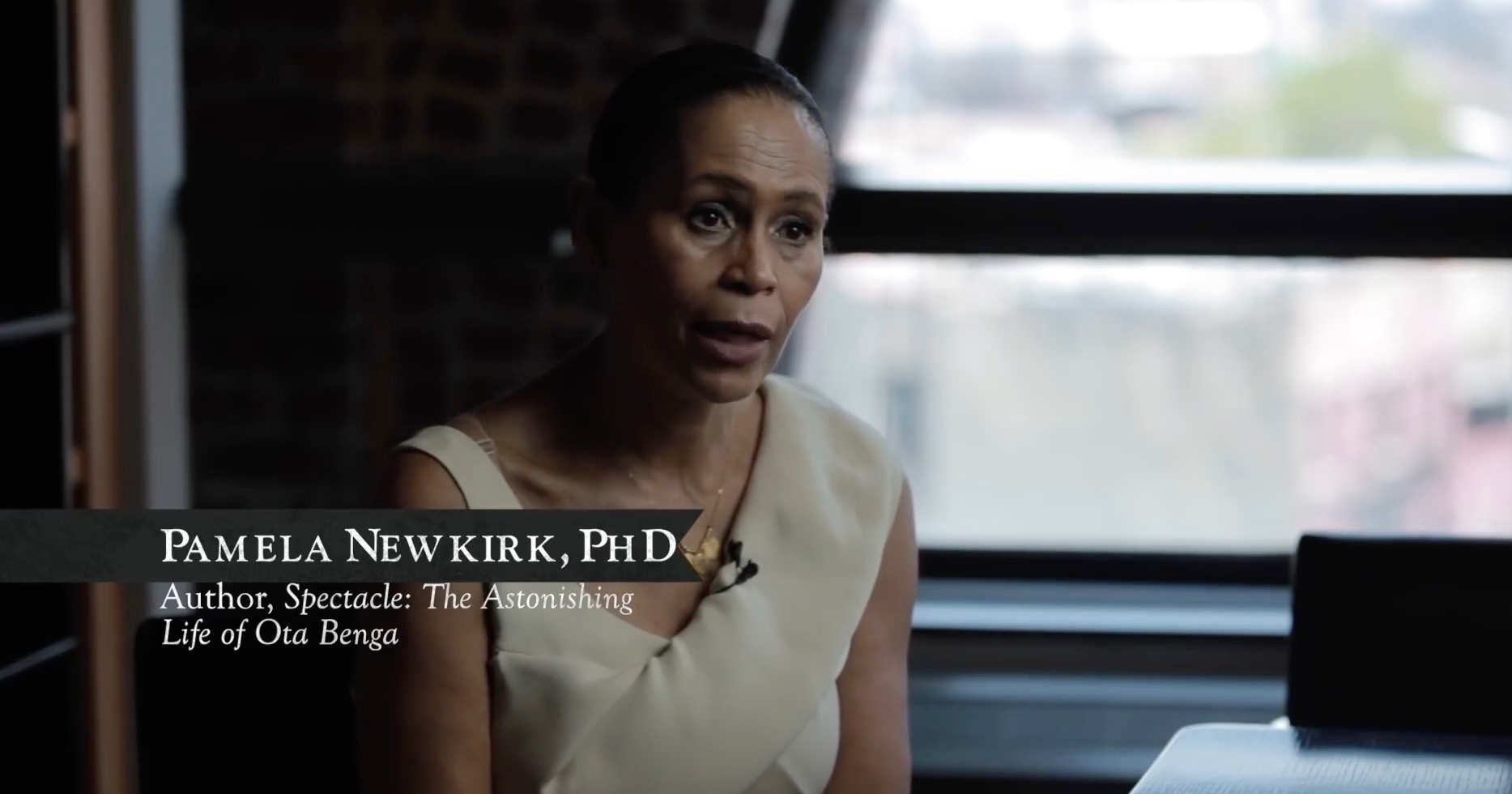

Pamela Newkirk is a journalist and historian who has documented the life of Ota Benga, the African teenager displayed at the Bronx Zoo as a lesson in Darwinian evolution. Thanks to Newkirk’s writing and to the documentary Human Zoos, by Discovery Institute political scientist John West, the Bronx Zoo recently apologized for its shameful treatment of a black man more than a century ago. But as Newkirk writes in a remarkably tough and fitting commentary for the BBC, the apology doesn’t go far enough.

An Inadequate Apology

It fails, among other things, to acknowledge the reality of a “cover-up” and “stonewalling” by the Bronx Zoo and, interestingly, by the New York Times. The zoo has long been in denial of what it did, as Newkirk shows. This is not reflected in the statement last month by Cristián Samper, who runs the Wildlife Conservation Society:

Instead of capitalising on the episode as a teachable moment, the Wildlife Conservation Society engaged in a century-long cover-up during which it actively perpetuated or failed to correct misleading stories about what had actually occurred.

As early as 1906 a letter in the zoo archives reveals that officials, in the wake of growing criticism, discussed concocting a story that Ota Benga had actually been a zoo employee. Remarkably, for decades, the ruse worked….

Then, in 1974, William Bridges, the zoo’s curator emeritus claimed that what actually occurred could not be known.

In his book The Gathering of Animals, he rhetorically asked: “Was Ota Benga ‘exhibited’ — like some strange, rare animal?” a question that he, as the man who presided over the zoo archives, would know best how to answer.

“That he was locked behind bars in a bare cage to be stared at during certain hours seems unlikely,” he continued, patently ignoring mountains of evidence in the zoological society archives that reveal just that.

An article about the exhibition, written by the zoo director, had in fact appeared in the zoological society’s own publication.

Nonetheless, Bridges wrote: “At this distance in time that is about all that can be said for sure, except that it was all done with the best of intentions, for Ota Benga was interesting to the New York public.”

This Black Life Mattered

He was an “employee”! The Zoo acted from the “best of intentions”! Amazing. As Newkirk points out, after her book, Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga, came out in 2015, the zoo refused to come clean about the past. They similarly stalled when John West’s documentary appeared. “Zoo officials,” writes Newkirk, “inexplicably refused to express regret or even respond to media inquiries.” It wasn’t until they were forced by events — George Floyd’s death and BLM protests — that the Zoo and the Conservation Society admitted this black life mattered.

The apology by Samper understates how long Ota Benga was imprisoned, and it obscures the actions of a revered figure in the Zoo’s history:

Curiously, Mr Samper did not mention William Hornaday, the zoo’s founding director who was also the nation’s foremost zoologist and founding director of the National Zoo in Washington, DC.

Hornaday had littered the cage housing Ota Benga with bones to suggest cannibalism and had brazenly boasted that Ota Benga had “the best room in the monkey house”.

As I have shown, too, the apology leaves out the role of Darwinian theory:

What’s missing…is any mention of where these evil ideas came from. What was the nature, the content, of the “pseudoscientific racism” that motivated Ota Benga’s treatment? To be accurate, the racism wasn’t “eugenics-based” it was “evolution-based.”

A Record of Denial

As for the New York Times, the newspaper of record likewise has a record of denial on the subject:

In 1916, following Ota Benga’s death, a New York Times article dismissed as urban legend tales of his exhibition.

“It was this employment that gave rise to the unfounded report that he was being held in the park as one of the exhibits in the monkey cage,” the article said.

The account, of course, contradicted the numerous articles that a decade earlier had appeared in newspapers across the country and in Europe.

Ota Benga died by his own hand in 1916, in Virginia, completing a heartbreaking journey from freedom to captivity. Today, his place of burial is unknown. Pamela Newkirk advocates naming the Zoo’s education center in his memory. That would be one step in the right direction. For more information about Ota Benga, about human zoos (not by any means limited to the Bronx Zoo), and about promoting Darwinian theory as the driving motivation behind the phenomenon, see John West’s multiple awards-winning film: