Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

ID Made Sassy: A New Book for Young People

The idea of translating books and articles into other languages is of course a routine one today. A book written in English might be unintelligible to, say, the Chinese-, Spanish-, or Russian-speaker, so the content of the book is locked to them until it’s been translated. According to a story told about the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, King Ptolemy of Egypt gathered 72 (some say 70) scholars and isolated them from each other. In his setting them to work, something remarkable occurred: “God put it in the heart of each one to translate identically as all the others did,” according to the Talmud.

If that’s how the Septuagint originated, it would indeed be a miracle: as a rule, different minds find different ways to translate the same ideas, in part because they are themselves different and in part because they are doing their work with different audiences in mind. That’s the case whether the text is the Bible or Shakespeare or Edgar Allan Poe — or the leading scientific advocates of the theory of intelligent design.

A Priority for Intelligent Design

Translating ID for various audiences has been a priority for the ID community. Some ID books are quite thick and erudite. It’s not just a matter of making them available to people who speak other languages but also to readers of different backgrounds and levels of sophistication, whose native language is English. Reaching young people is a particular challenge. It’s a tougher one today than 25 years ago when the Center for Science & Culture was getting ready to launch. In those 25 years, the Internet took over and shortened all of our attention spans. That’s one problem.

So congratulations to Douglas Ell for taking up the challenge of explaining intelligent design to the young. His new book, Proofs of God: A Conversation between Doubt and Reason, is the first ID book ever to which I would apply the label “sassy.” His concept is a dialogue between Doubt and Reason, who sass each other merrily. The Septuagint this is not, but that’s not what you’d want, obviously, if the aim is to reach an easily bored teenager:

DOUBT. How do you prove the existence of God?

REASON. Evidence! Facts! Things with no other explanation! You know what they say — “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

DOUBT. They? What bozo said that?

REASON. Sherlock Holmes.

DOUBT. Who’s he?

REASON. I like a literary person.

DOUBT. Whatever. No such evidence.

REASON. There is! Undeniable! To me, and to many, science now proves God.

DOUBT. You can’t prove God!

REASON. I can prove God three ways.

DOUBT. Banana peels. Give me a hint.

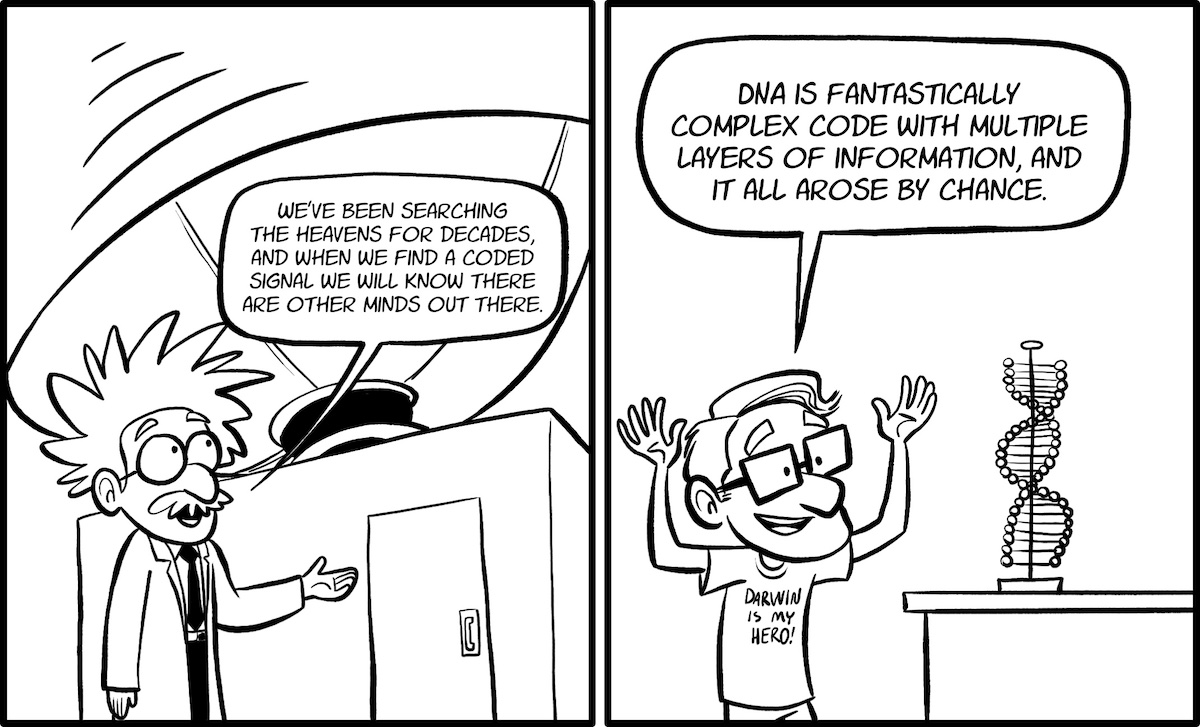

REASON. Every kind of animal has working code that is new and doesn’t resemble the code in any other kind of animal. You—

DOUBT. Back up. What’s code?

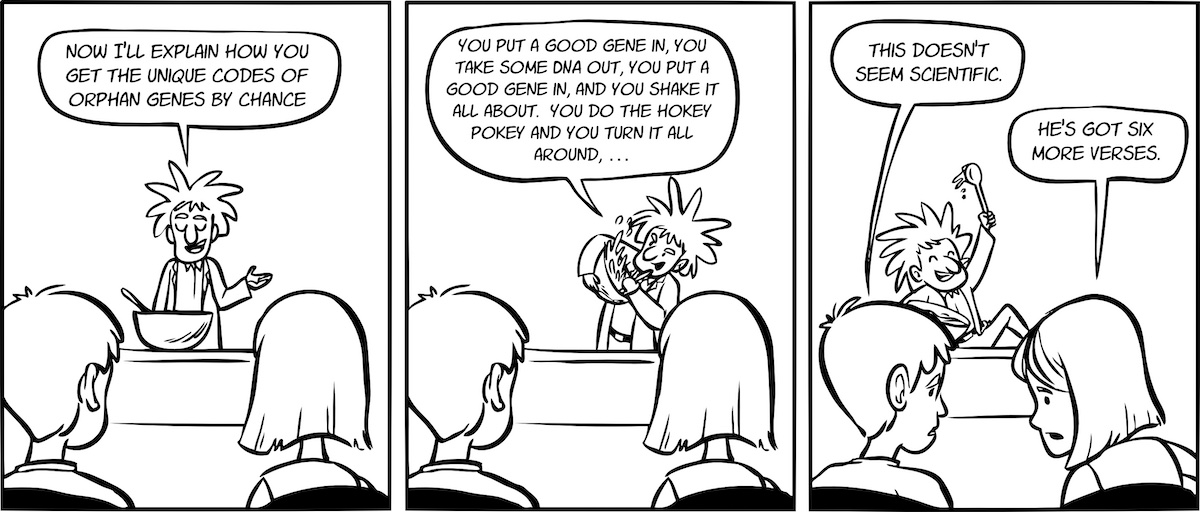

That is how the book opens, going on to cover five days, one day per chapter, of fast-moving dialogue between the quarreling participants. They cover “The Numbers Proof” (in three steps), “The Common Sense Proof,” “The Logic Proof,” “The Nonsense of Cumulative Selection,” and “Doubting Darwin.” By the end, Reason has won over Doubt and commissioned him, in Judeo-Christian style, to share what he’s learned with others. It is just 93 pages long and filled with some fairly sassy cartoons. Mr. Ell, a lawyer in Washington, D.C., and a math and physics graduate from MIT, knows his intelligent design. You could argue with the title of the book. Does ID “prove God”? That’s not what I would say. But let’s not be overly fussy.

“Counting to God”

Evolution News reviewed Ell’s earlier book, Counting to God: A Personal Journey Through Science to Belief, here back in 2014, and commented that “A lot of books — many of them very good — have been written about the debate over intelligent design. But rarely does one come along that combines a compelling story of the author’s personal journey to faith with a well-written, comprehensive, easy-to-read presentation of the scientific evidence.” This new book takes the previous one and updates it creatively for an entirely different demographic.

Will it speak to every bored teenager in your life? Of course not. No book could. Human beings are unique. Ideally, you’d want a book individually written for every human on the planet.

That project is beyond humanity’s current staffing resources. Yet the work of translation goes on. Thank you to Douglas Ell for his energetic contribution.