Evolution

Evolution

Human Origins

Human Origins

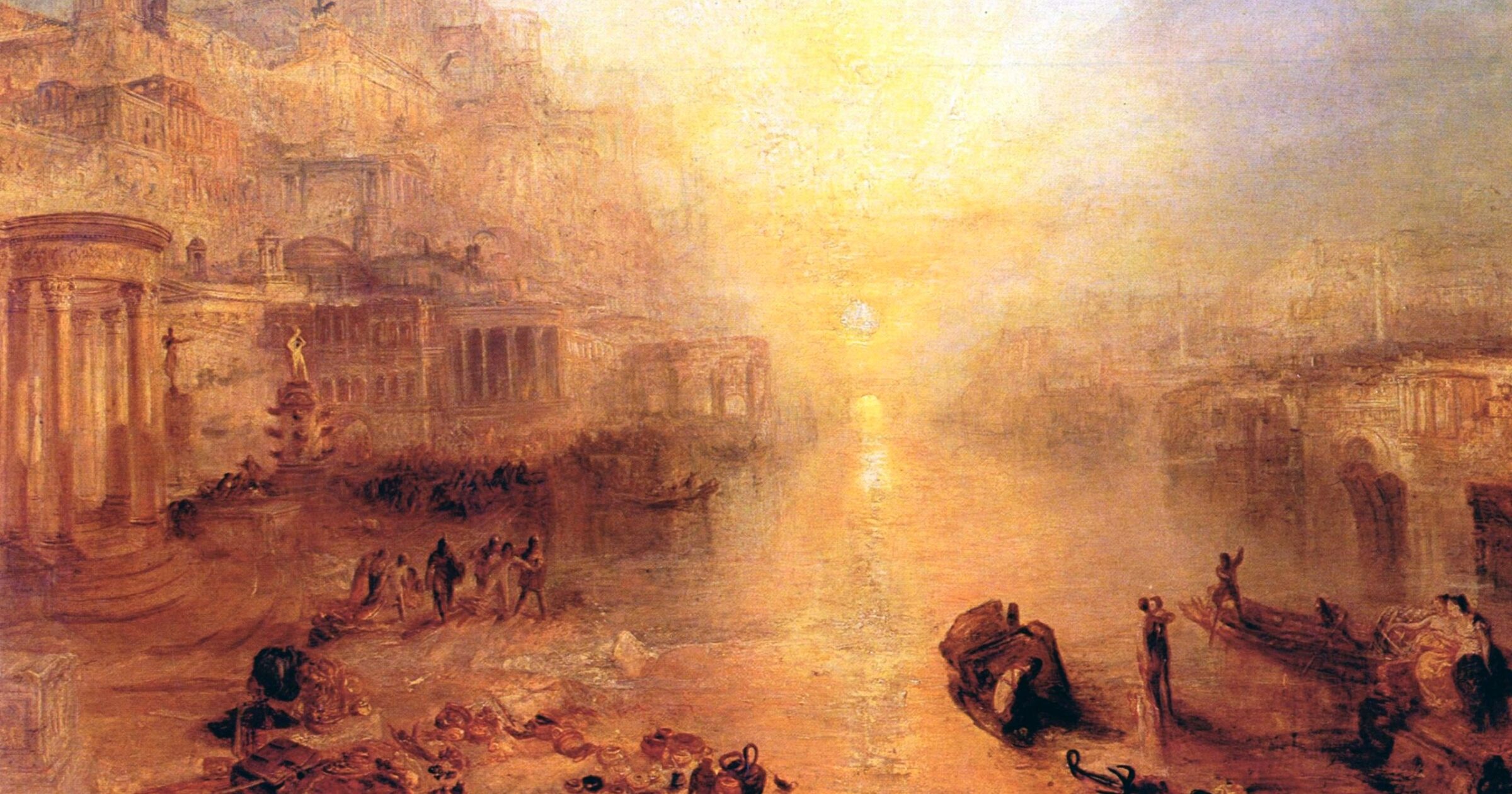

Ovid in His Exile

Editor’s note: We are delighted to welcome Science After Babel, the latest book from mathematician and philosopher David Berlinski. This article is adapted from Chapter 14.

Schermerhorn Hall at Columbia University was the scene of many strange experiments. One day, a very young chimpanzee escaped from the building and, flushed with its freedom, began to gambol and frolic on the pathetic square of shabby and well-worn grass that served as a lawn in front of the building. A crowd quickly collected. The mathematician Lipman Bers joined me. A scruffy puppy noticed the commotion and scooted into the square where the chimpanzee was playing. The two animals promptly became friends, but the puppy, it soon became apparent, was less intelligent than the chimpanzee. Again and again he would find himself maneuvered into absurd and humiliating positions. “So stupid,” snorted Bers, referring to the dog. Pleased and flattered by the attention, the chimpanzee began to refine his act and play to the crowd, using gestures, and even facial expressions — the universal rictus of triumph, for example — that everyone recognized. After a while, the chimpanzee’s frantic owner, a rather dishy young woman, I recall, collared him in the courtyard and the game was over. As the chimpanzee was led away, he waved to the crowd, a true sportsman. The puppy sat on its haunches and panted assiduously.

The Incompetent and the Indifferent

I learned later from Bers that research biologists were trying to teach the chimpanzee American Sign Language. They had been working with an older animal, but evidently the beast, while learning some signs, grew unsurprisingly to detest his owners, who finally shipped him to a zoo in San Diego. There he occupied himself unprofitably in attempting to teach the other animals to sign, a splendid case of the incompetent endeavoring to instruct the indifferent.

“A vast tragedy,” Bers remarked sentimentally, “like Ovid in his exile.”

I mention this sad little story only to remark on its ironic conclusion. For a time during the 1970s, a number of biologists were actually convinced that they had taught chimpanzees and great apes to talk; many of them reported long conversations, chiefly about bananas (Me: More!), that they held with their charges. Their research was no sooner published than it was accepted and believed, largely, I think, because a crude Darwinian theory — there is no other — made it difficult to imagine that profound and ineradicable differences exist between human beings and the rest of the animal world. Penny Peterson at Stanford, Herbert Terrace at MIT, and David Premack at the University of Pennsylvania all convinced themselves that somehow the great apes had sat in stony silence throughout the vast reaches of biological time only because they lacked human conversational companionship.

Nothing to Say

The inevitable, skeptical reaction soon set in. Videotapes taken of chimpanzees revealed, when carefully analyzed, that what had passed for chimpanzee conversation was nothing more than prompted signings in the best of cases — a record of the beast’s pathetic endeavor to say whatever it was that his trainer wished him to say; in the worst of cases, the beast simply babbled (More Me More More!), his signs utterly devoid of meaning. Herbert Terrace, who had wasted years in browbeating the poor creatures, examined videotapes of his own encounters with his animals and came away shaken. Some work, of course, continues, but to little effect. Ever credulous, scientists now report that they have engaged the dolphin in stimulating conversation. Next year, no doubt, it will be the turkey.

Seventeenth-century Jesuits wondered why dogs do not talk. Their conclusion bears repeating. They have nothing to say.