Evolution

Evolution

Faith & Science

Faith & Science

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

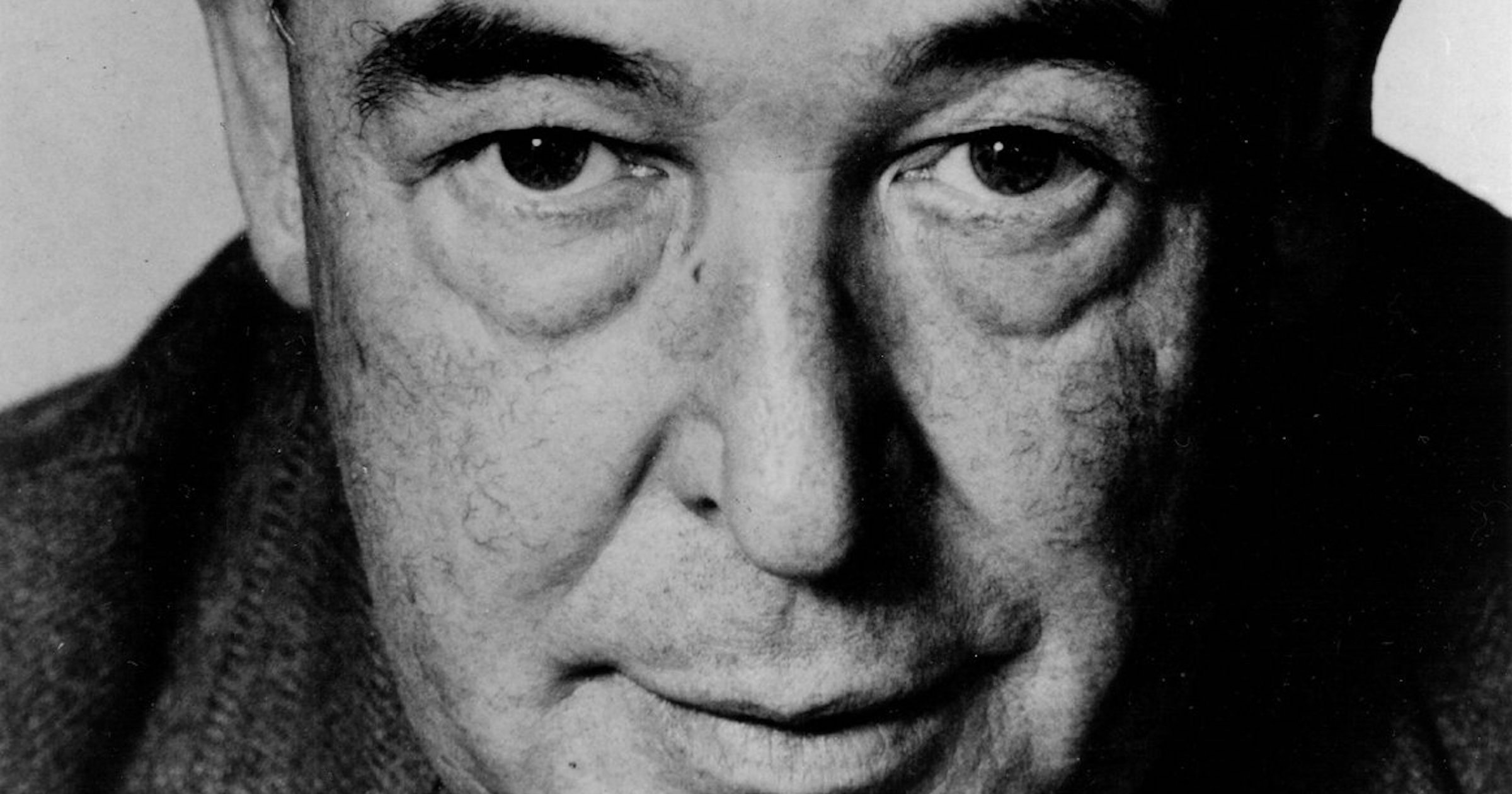

C. S. Lewis and Theistic Evolution

Editor’s note: To mark the release on November 3 of the new C. S. Lewis biopic, The Most Reluctant Convert, we are running a series of articles exploring C. S. Lewis’s views on science, mind, and more.

SPECIAL LIMITED-TIME OFFER: Get a FREE chapter exploring C.S. Lewis’s views of intelligent design from the book The Magician’s Twin

Was C. S. Lewis a theistic evolutionist? He certainly was open to the possible common descent of humans from lower animals, although he also expressed some reservations (see the full Chapter 6 of my book The Magician’s Twin for more details).

But I would argue that regardless of Lewis’s views on common descent, it would be misleading to classify himself as a theistic evolutionist as that term is commonly understood today.

Defining “Theistic Evolution”

Theistic evolution can mean many things, including a form of guided evolution, but many contemporary proponents of theistic evolution are more accurately described as theistic Darwinists. That is, they do not merely advocate a guided form of common descent, but they are attempting to combine evolution as an undirected Darwinian process with Christian theism. Although they believe in God, they strenuously want to avoid stating that God actually guided biological development.

For example, Anglican John Polkinghorne wrote that “an evolutionary universe is theologically understood as a creation allowed to make itself.” Former Vatican astronomer George Coyne claimed that because evolution is unguided “not even God could know… with certainty” that “human life would come to be.”

And Christian biologist Kenneth Miller of Brown University, author of the popular book Finding Darwin’s God (which is used in many Christian colleges), insists that evolution is an undirected process, flatly denying that God guided the evolutionary process to achieve any particular result — including the development of us. Indeed, Miller insists that “mankind’s appearance on this planet was not preordained, that we are here… as an afterthought, a minor detail, a happenstance in a history that might just as well have left us out.”

Unguided Creation?

In short, many modern theistic evolutionists want to retain a belief in a Creator without actually affirming the guidance of that Creator in the history of life. In their view, the Creator delegated the development of life to a self-contained mindless process from which mind and morals emerged over time. Modern theistic evolution’s attempt to strike a third way between materialism and intelligent design with a kind of emergent evolution has all the logical coherence of a circular square, or theistic atheism.

Lewis was familiar with attempts in his own day to imbue blind evolution with some sort of purposiveness while still denying the operation of a guiding intelligence, and he was not persuaded. This was where he ultimately broke with Henri Bergson, a French natural philosopher and Nobel Prize-winner whose anti-Darwinian writings had heavily influenced Lewis.

Bergson, in addition to critiquing natural selection, offered his own alternative to Darwinism, a muddled proposal for a vital force that somehow impels the evolutionary process toward integrated complexity without the need for an overarching designer. Lewis never attacked Bergson’s critique of Darwinian natural selection, but after he became a Christian he repeatedly attacked Bergson’s non-intelligent alternative. He did the same with George Bernard Shaw, who extolled a similar view to Bergson of “emergent evolution,” the view that although evolution is not actually guided by an overarching intelligent purpose, purposeful structures that transcend blind matter somehow emerge from the process.

In a section of Mere Christianity that is too little read, Lewis dissects this supposed third way between outright materialism and a history of life guided by design:

People who hold this view say that the small variations by which life on this planet ‘evolved’ from the lowest forms to Man were not due to chance but to the ‘striving’ or ‘purposiveness’ of a Life-Force. When people say this we must ask them whether by Life-Force they mean something with a mind or not. If they do, then ‘a mind bringing life into existence and leading it to perfection’ is really a God, and their view is thus identical with the Religious. If they do not, then what is the sense in saying that something without a mind ‘strives’ or has ‘purposes’? This seems to me fatal to their view.

In his novel Perelandra, Lewis satirizes the incoherence of the emergent evolution view, which he assigns to the villain of the story, Professor E. R. Weston, a scientist run mad. Lewis gives Weston a speech of non-sequiturs and mumbo-jumbo where he solemnly appeals to “the unconsciously purposive dynamism” and “[t]he majestic spectacle of this blind, inarticulate purposiveness thrusting its way… ever upward in an endless unity of differentiated achievements toward an ever-increasing complexity of organization, towards spontaneity and spirituality.” Weston ultimately identifies this blind and unconscious purposiveness with what he calls “the religious view of life” and even with “the Holy Spirit.”

The hero of the story, Dr. Elwin Ransom, is not impressed. “I don’t know much about what people call the religious view of life,” he replies. “You see, I’m a Christian. And what we mean by the Holy Ghost is not a blind, inarticulate purposiveness.”

De Chardin’s Emergent Evolution

Near the end of his life, Lewis read prominent theistic evolutionist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s posthumously published book The Phenomenon of Man, which proposed yet another kind of emergent evolution. Lewis filled his copy of the book with critical annotations such as “Yes, he is quite ignorant,” “a radically bad book,” and “Ever heard of death or pain?” (The last comment responded to de Chardin’s statement that “Something threatens us, something is more than ever lacking, but without our being able to say exactly what.”) In his letters to others, Lewis called de Chardin’s book “both commonplace and horrifying,” and he derided de Chardin’s position as “pantheistic-biolatrous waffle” and “evolution run mad.”

Lewis’s rejection of emergent evolution exposes why his way of thinking is ultimately so friendly to intelligent design. Lewis knew that ultimately there is no third way, no half-way house, no magical hybrid: Biological development is either the result of an unintelligent material process or a process guided by a mind, aka intelligent design.

One can’t split the difference. One has to choose. That being the case, Lewis thought that a mind-driven process is a far more plausible option than a mindless one.

This essay was adapted from “Darwin in the Dock,” Chapter 6 of The Magician’s Twin, edited by John West. For reference notes and sources, please consult the book version.