Culture & Ethics

Culture & Ethics

Evolution

Evolution

In the Footsteps of Social Darwinist Cesare Lombroso

In the history of crime-fighting, Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso is notorious. During the 19th century, he popularized the notion that you could tell if someone was a criminal by looking at the person’s facial features and the shape of his head.

Lombroso’s ideas were quack science and a form of phrenology. But they were taken seriously by criminologists and public officials around the world until they were debunked.

Evolutionary Throwbacks

Heavily influenced by the work of Charles Darwin, Lombroso thought that many people who commit crimes were “born criminals” who represented throwbacks to an earlier, sub-human stage of evolution. Such criminals were not moral agents, and their heredity and biology made them irredeemable.

I wrote about Lombroso and the “new school of criminology” he helped pioneer in chapter three of my book Darwin Day in America. So when I recently visited the Italian city of Turin, I jumped at the opportunity to learn more about Lombroso, who was was a longtime professor of forensic medicine at the university there. To this day, the University of Torino houses a museum devoted to Lombroso’s life and work.

The museum’s collections are rather macabre, featuring row after row of the skulls of the criminals Lombroso studied. In fact, in a place of honor, the museum even displays the full skeleton of Lombroso himself. Lombroso apparently willed both his skeleton and his brain to the museum, and he wanted his skeleton put on public display. I don’t know whether he wanted his brain displayed as well, but it wasn’t, and the staff person I asked didn’t know where it was currently stored.

A Candid Portrayal

To its credit, the museum offers a fairly unflinching glimpse into Lombroso’s life. In particular, it makes clear how Darwinian evolution provided much of the inspiration for Lombroso’s ideas.

For example, Darwinian racism undergirded his views of blacks. As the museum explains:

Lombroso distinguished… “the white man and the man of colour,” and he believed that black skin represented a link between the apes and the white man.

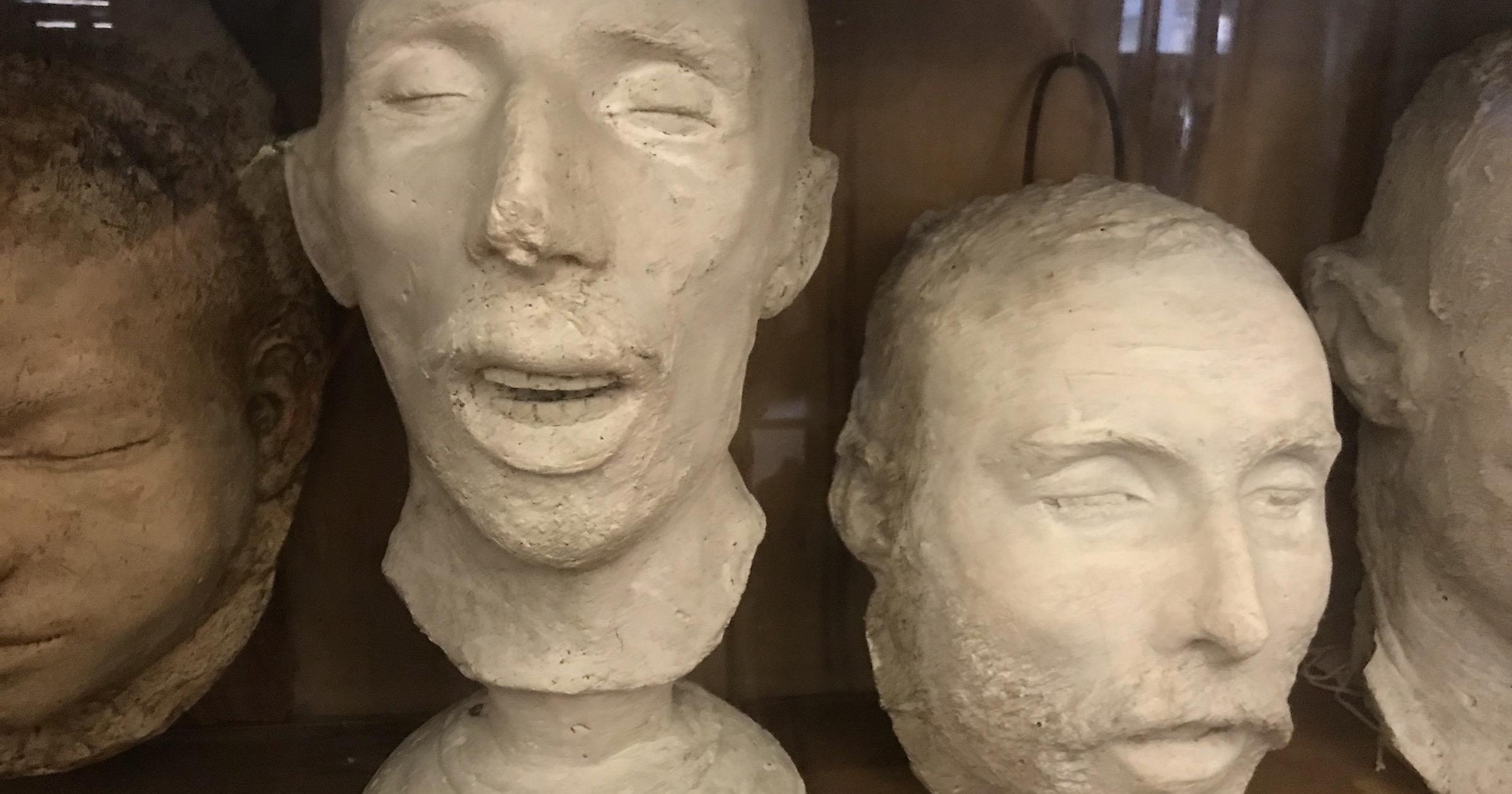

Out of respect, the museum asks visitors not to take photos of the skulls and skeletons on display. So I wasn’t able to take a photo of Lombroso’s skeleton. But some of the most disturbing materials in the museum aren’t actual human remains. They are the grim plaster reproductions of the faces and heads of prisoners Lombroso studied. I did take pictures of the reproductions. They are haunting.

For the most part, the Lombroso museum doesn’t have information about the people whose plaster face masks are on display. So we don’t know their stories as human beings. They have faces, but in a very real sense they remain faceless. They are reduced to mere specimens for scientific study.

Out of Luck

In fairness to Lombroso, he apparently supported more humane treatment for certain criminals. But if you were deemed a “born criminal,” you were out of luck. In his words:

The revelation that there are persons organically predisposed to evil, atavistic reproductions not only of the most savage men but even of the fiercest animals, of carnivores and of scavengers, far from making us more compassionate toward them, as is claimed, steels us against any form of mercy; since they no longer appear to be our similars, but fierce beasts….

As I describe in detail in Darwin Day in America, evolution-inspired criminologists like Lombroso had a serious impact on the criminal justice system. Darwin’s ideas had consequences for society that are more far-reaching than most people realize: